Dark comedy or tragedy? The dire straits of Iran's economy

By Mahdi Ghodsi

Welcome to the third edition of Clingendael’s blog ‘Iran in transition’ that tracks different dimensions of the evolution of protests and governance in Iran. In our previous blog, Hamidreza Azizi and Erwin van Veen examined Iran’s foreign relations with regard to the transitional state the country has entered into since the 2022/2023 protests. In this blog, Madhi Ghodsi takes a hard look at the economic performance of Iran’s ruling elites and analyses some of its effects on livelihoods, social justice and protests.

Introduction

Iran is currently experiencing its deepest and longest economic crisis in its modern history. Its root causes are specific failings of its political system. From an economic perspective, two issues are paramount. First, the ideological and geopolitical objectives of Iran’s ruling elites generate external pressures, such as tense regional relations and international sanctions, that reduce economic prospects and decrease social welfare. Otherwise put, Tehran pursues political objectives through its foreign policies in a manner that generates high domestic socio-economic costs. This achieves the opposite effect of Supreme Leader Khomeini’s stated intention that the revolution should eradicate income inequality and poverty through responsible use of Iran’s oil revenues. Second, Iran has levels of corruption that impose deadweight losses on its economic prosperity. Corruption reduces the private sector dynamics and hinders the growth of social capital. With these root causes in mind, I outline four effects of Iran’s poor economic policies in what follows, and relate these to the present situation of persistent social unrest.

Effect #1: A drop of GNI growth and investment between 1976 and 2021

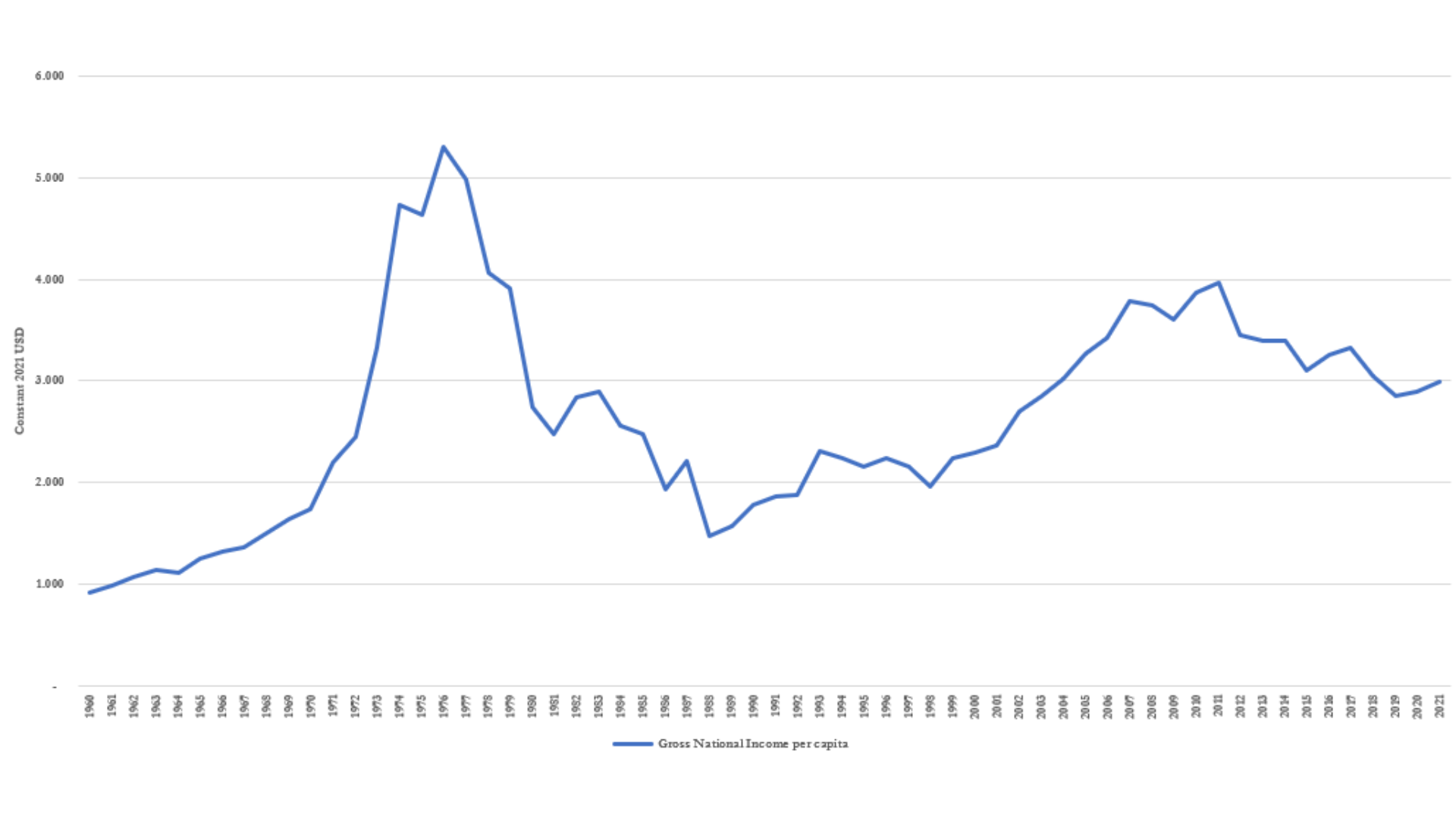

If we take a look at the evolution of Iran’s gross national income (GNI) per capita in constant prices, which is a common indicator of societal welfare, it is remarkable that GNI stood at 57% in 2021 of its 1976 level (see Figure 1). In other words, Iran’s GNI has declined significantly over time.

Figure 1 – Development of GNI per capita in constant 2021 USD, 1960-2021 (click to enlarge)

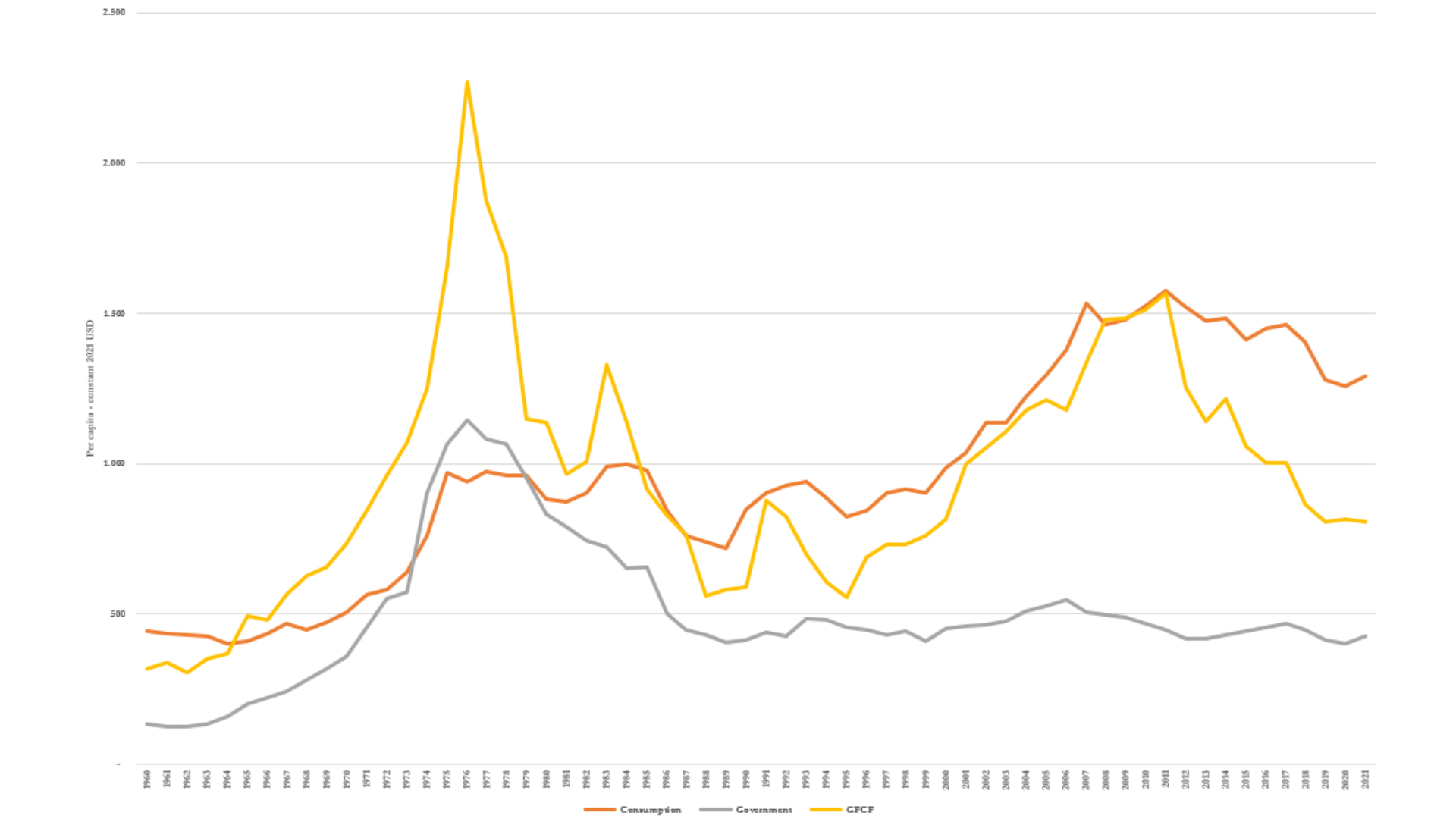

To understand the 1976 peak in Iran’s GNI, it is worthwhile to bear in mind that the country maintained good relations with the international community in general, and the West in particular, throughout the 1970s. This allowed the country to play an influential role on the global oil market and in the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). Iran enjoyed historically high oil revenues at the time as it produced roughly 5.9 million barrels per day (bpd), which amounted to 20% of OPEC’s production back then. In part, this was due to the Yom Kippur war of 1973 and the ensuing OPEC oil embargo. The Shah and his government spent these revenues on infrastructure, naval bases, nuclear power plants, expansion of armed forces and credit facilitation, which empowered the private sector. Such measures also increased the amount of Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF) to its historic high of USD 2,270 in 1976 (per capita, in constant 2021 USD – see Figure 2 below). GFCF is part of GNI and serves as proxy indicator for how much of the new value added that is generated in an economy is invested rather than consumed, i.e. higher amounts of GFCF suggest higher future rates of economic growth.

This growth trajectory declined steeply after 1976 due to the unrest preceding and during the Islamic Revolution as well as the destruction and loss of life during the Iran-Iraq war (1980-1988). Growth recovered somewhat between 1990 and 2010 and then declined again in the face of international sanctions. For example, GFCF hovered on average around 25% of Iran’s total GNI between 1960 and 2010, but it decreased to 21% after 2012 due to the intensification of international sanctions. GNI dropped to 76% in 1979 and 57% in 2021 compared with its 1976 peak (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 2 – Development of components of gross domestic product per capita in Constant 2021 USD, 1960-2021 (click to enlarge)

Effect #2: Population growth without parallel investment in opportunities

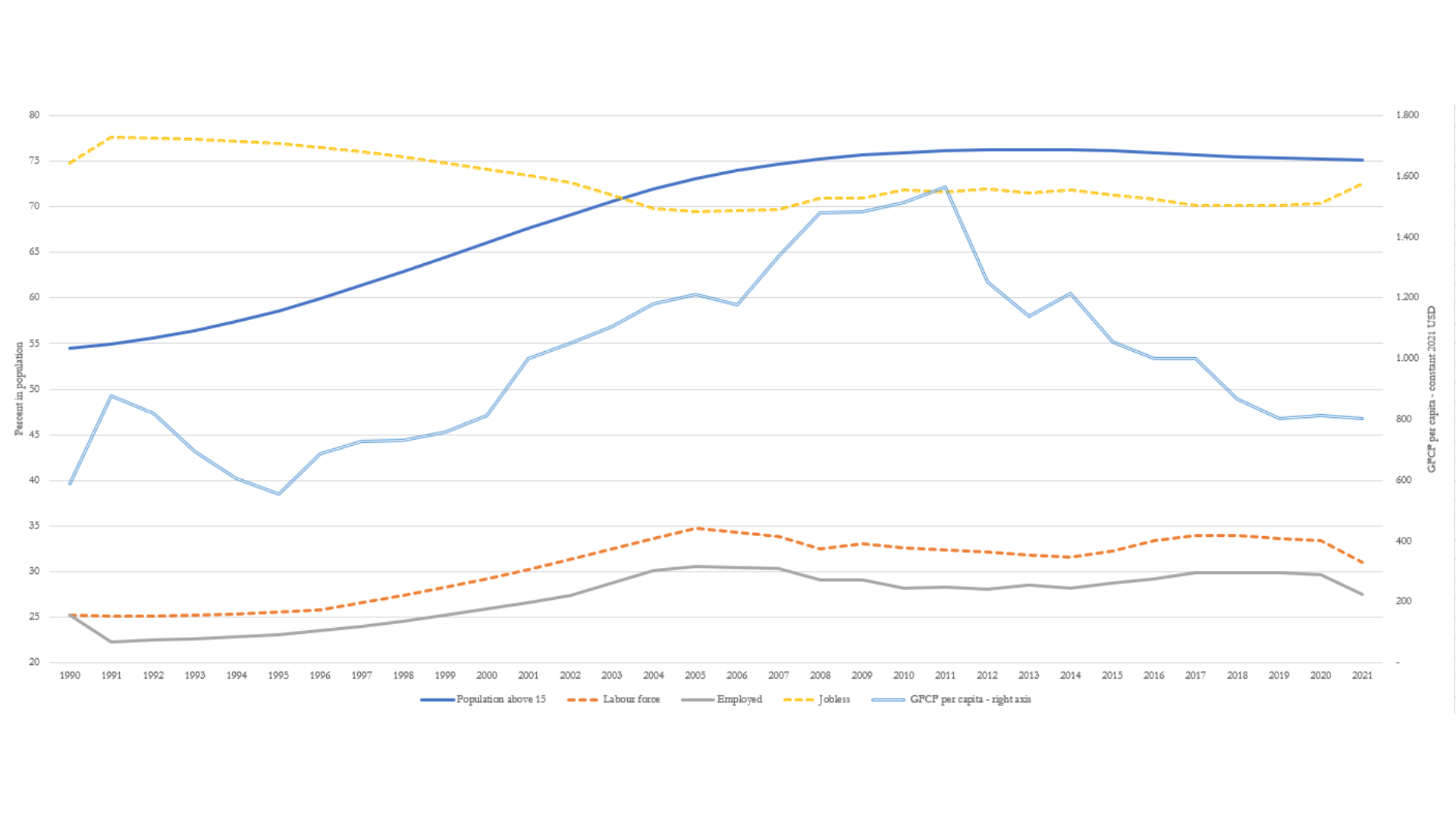

In the aftermath of the Iran-Iraq war (1980-1988), Supreme Leader Khomeini promoted population growth in a bid to regenerate wartime losses. He believed that a large population translates into greater geopolitical acumen even though it risks having several negative economic effects if accompanying policies are not put in place. For example, the government needed development plans to improve education, foster investment and create jobs once the new generation came of working age. The reformist government of Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005) was partly successful in implementing such policies by increasing private investment, inviting foreign direct investment (FDI), improving the infrastructure and oil production capacities, increasing private consumption (Figure 2 above) and creating more jobs (Figure 3 below).

President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (2005-2013) enjoyed the fruits of his predecessor’s policies during another period of high oil prices. However, instead of further increasing investment to generate more jobs for those Iranians reaching working age, he used public revenues to introduce cash handouts. While these were initially popular, in just a few years they lost much of their value due to the inflation that they induced. This proved to be an unsound economic policy that stored problems of unemployment and inflation up for the future.

Figure 3 – Development of demography, labour market conditions, and GFCF per capita, 1990-2021 (click to enlarge)

Some of the Islamic Republic’s foreign policies, such as its stated intent to wipe Israel from the map and its development of nuclear capabilities, furthermore triggered sanctions that discouraged foreign investment and reduced economic growth, including job creation. As Figure 2 shows, Gross Fixed Capital Formation reached its post-revolution peak of USD 1,566 per capita in 2011. When international sanctions intensified, it declined to USD 804 per capita in 2021. Net investment has been negative since 2019 because capital has depreciated at a faster rate than GFCF.

Effect #3: Rising poverty and unemployment

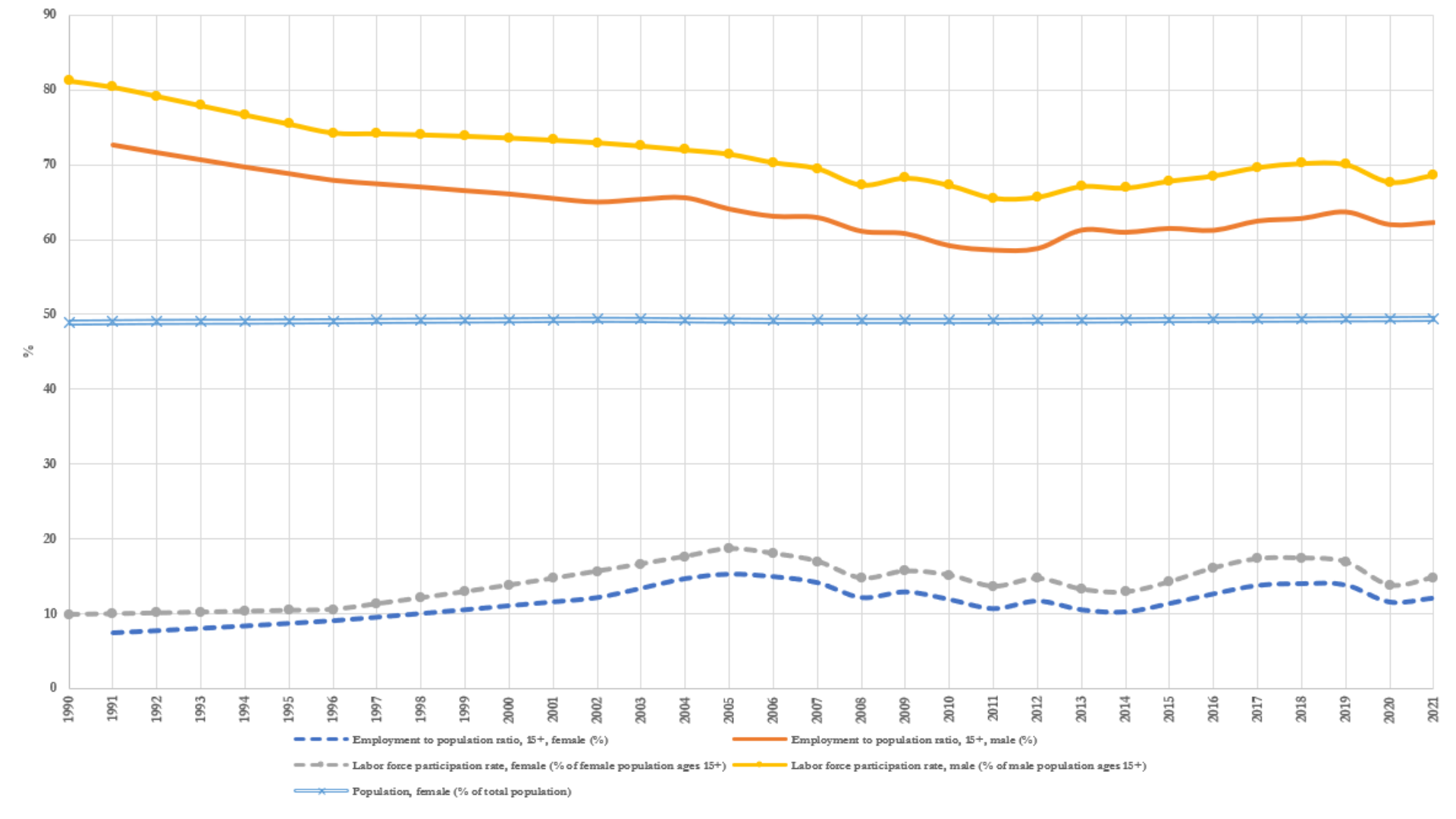

Only about 27.5% of Iran’s population has been in formal employment over the past decades (Figure 3). In neighbouring Turkey, about 37% of population is formally employed and in an advanced economy like Austria around 43% of population is working in the formal economy. This suggests that the remainder (i.e. 72.5%) of Iran’s population is either jobless, retired or employed in the informal sector. They receive lower salaries or cash handouts, which are not fully adjusted to inflation. Labour conditions for women have been worse than those for men. While 62.2% of men aged above 15 years old are employed in the Iranian economy (formal and informal), only 12.2% of women are (aged above 15, 2021) (Figure 4). Employing one out of eight women hints at a serious gender gap in the labour market. In neighbouring Turkey, the corresponding figure for women is 28% and in Austria it is 52.5%.

Figure 4 – Labour market conditions in Iran, female versus male, 1990-2021, 1990-2021 (click to enlarge)

Effect #4: Inflation increases

The sanction regime that US President Trump put in place in 2018 rapidly caused a fiscal crisis in the Islamic Republic because plunging oil revenues made it impossible for the government to finance its expenditures. More precisely, Iran’s crude oil and condensate exports dropped from more than 2.7 million bpd in June 2018 to less than half a million bpd in April 2019, which was especially due to secondary sanctions. Even with the Biden administration turning a blind eye on Iran’s oil exports since 2021, Iran could no longer export oil or gas at full capacity due to overdue maintenance requirements. The financial shortfall of the Iranian government could only be covered by printing money and selling government assets. The former caused prices to soar and the second encouraged corruption. Moreover, the geopolitical instability resulting from US withdrawal from the deal generated a negative shock to financial markets and the rial depreciated in consequence. The subsequent rise in the price of imported goods due to sanctions also caused a price hike, which interacted with an expanding money supply needed to finance the government’s budget.

Several consecutive years of high inflation of around 40-50% have shrunk the real income of many employees – especially those in government service – despite benefitting from a nominal increase of 10-20% in the national budget that Ibrahim Raisi’s government submitted to parliament in 2021. Prices rose further in the summer of 2022 when the government removed the preferential exchange rate (1$=42,000 rials) that was introduced by Hassan Rouhani’s governments and which financed the import of primary commodities such as food, medicine, and livestock feed. This measure increased food prices by 100% or more. The consumer price index (CPI) of urban areas collected by the Statistics Center of Iran increased by 483% in the past five years (up until 20 February 2023).

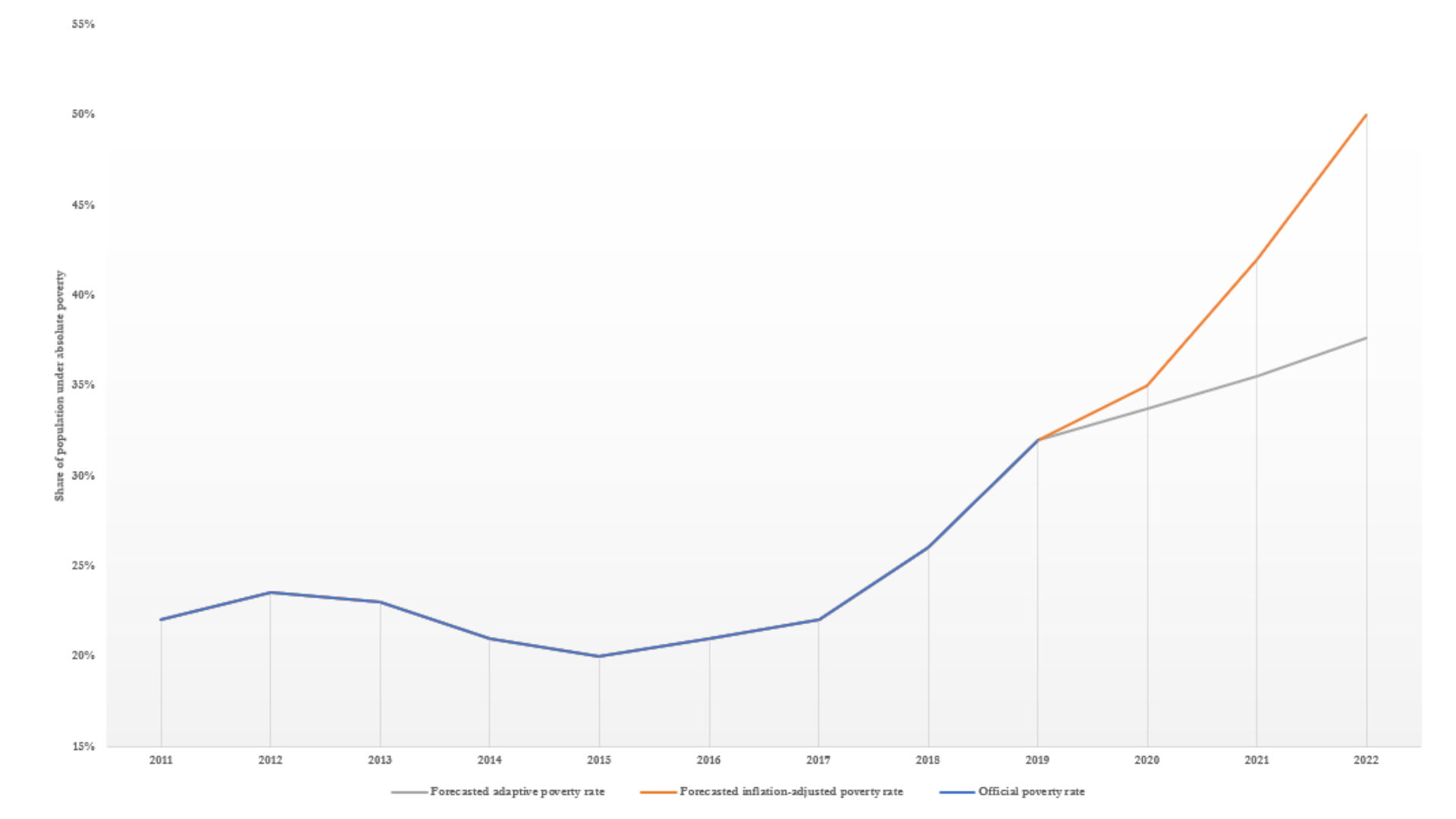

Figure 5 – Development of poverty rate, official and estimated, 2011-2022 (click to enlarge)

As the number of unemployed grew and the inflation rate depressed the value of cash handouts, the reported poverty rate exceeded 33% already in 2019 (Figure 5). Today, the poverty rate likely exceeds 50% of the population. Based on calorie use per capita, the poverty rate might hover around 60%. While the real income of many Iranians has decreased substantially over the past few years, the government nevertheless increased spending on its security apparatus, media and propaganda as well as its clerical commercial operations to squash protests, maintain domestic rule and continue a set of assertive foreign policies.

Figure 6 – Development of national budgets in Iran’s GDP – 1980-2021 (click to enlarge)

Corruption as cause and effect of economic trouble

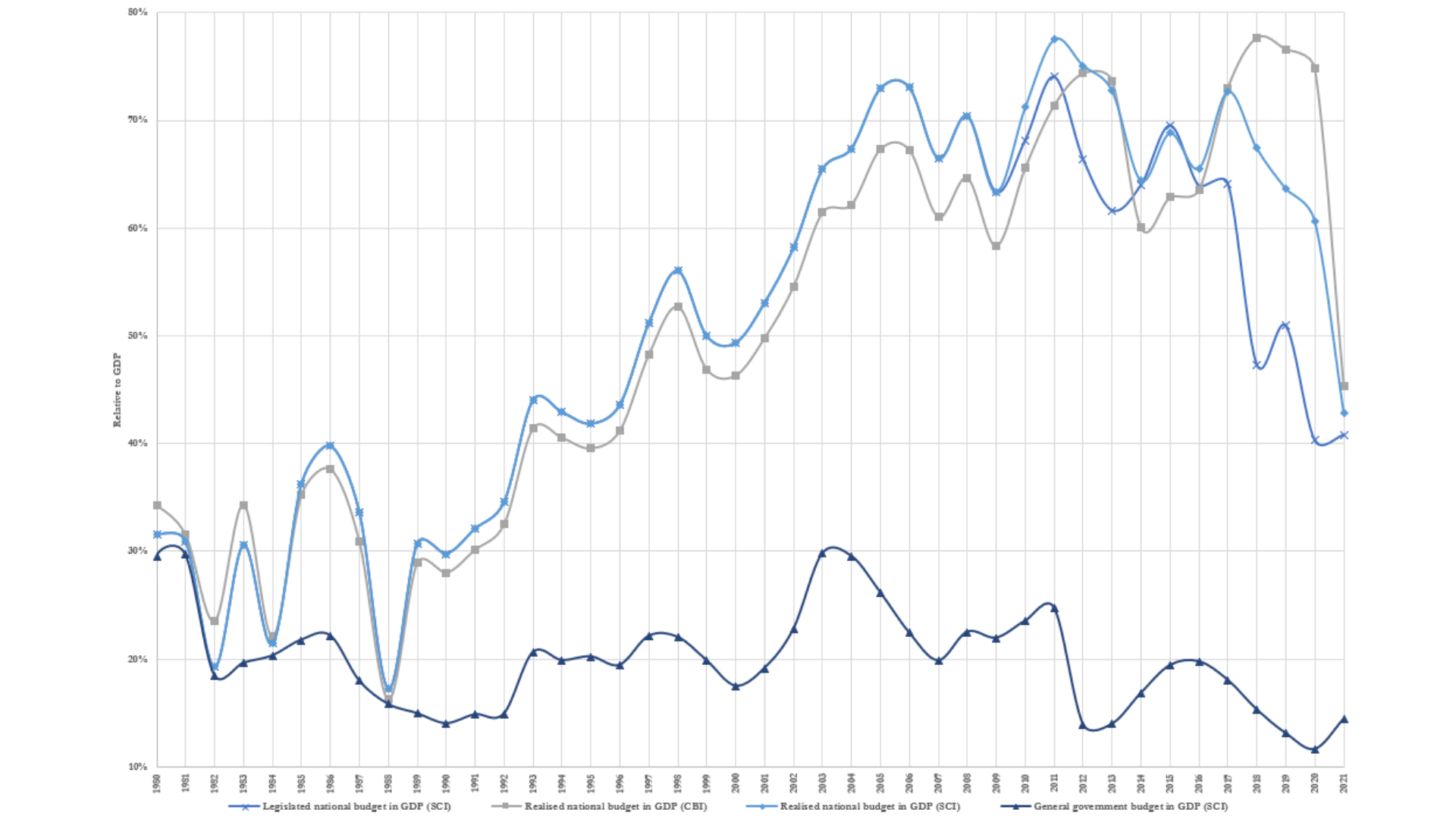

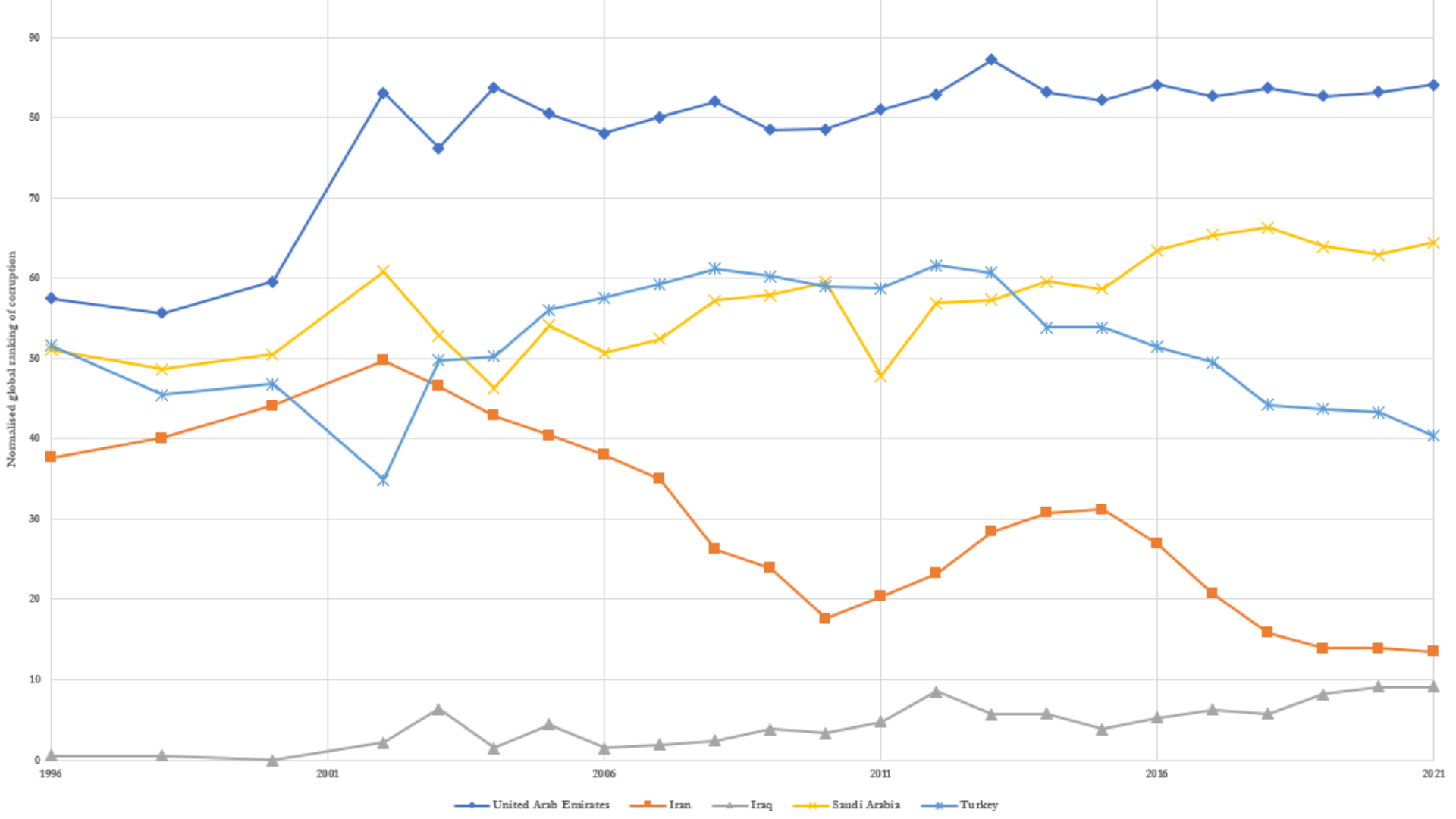

Despite this poor economic situation, president Raisi keeps repeating that Iran is a “train of progress.” However, an ever greater part of the economy is run by government and individuals loyal to it – roughly 75% of total Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as reported by the Central Bank of Iran (CBI) (see Figure 6). To this figure, one needs to add the budget and value added of semi-public companies such as foundations (Bonyâds, e.g. Astan Quds Razavi owns a share of almost all land in Iran) and executive offices that are managed by the office of the Supreme Leader (Setâd, e.g. Setâd-e Ejrây-ye Farmân-e Emâm). Including such actors and their assets brings Iran’s public economy to around 80-90% of Iran’s GDP, which crowds out nearly all formal private enterprise. Practically, this also brings endemic corruption about that provides substantial rents to the elites running the Islamic Republic. It is no exaggeration to say that Iran’s political system has turned a once reasonably productive economy into an unproductive rent factory. Figure 7 shows that corruption rates in Iran were standard compared with regional peers in 2001-2002, but subsequently increased to the effect of bringing Iran to the bottom of the regional ranking.

Figure 7 – Normalised global ranking of corruption of selected countries across 214 countries – 1996-2021 (click to enlarge)

The law of unintended consequences

The government’s encouragement of population growth after the Iran-Iraq war in combination with increasing unemployment forced young Iranians to continue to study or to emigrate. As a result, human capital in the country increased in the course of time. Young and well educated generations voted a moderate president into office – Hassan Rouhani (2013-2021) – with the aim of restoring ties with the international community, encouraging foreign investment, and achieve greater economic prosperity. Hardliners have sought to sabotage this process at various turns, and especially to prevent the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) from bearing fruit (its opportunity cost in the form of sanctions has been estimated at about $200 billion). The most infamous acts of sabotage were the 2016 US-Iran naval incident and publicly testing missiles after the conclusion of the JCPOA under slogans like “Death to America, Death to Israel, Death to Al-Saud”. Iran’s current Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, subsequently rejected negotiations about security matters like Iran’s regional network of armed groups and its missile program. US president Donald Trump used such developments to rescind US participation in the nuclear deal, which he had already hinted at on the campaign trail. At the time, many economists predicted a gloomy economic future for Iran as a consequence. They were right. The economic factors discussed above all indicate that the current political system in Iran is failing to develop a prosperous economy that produces sufficient levels of growth that allow national development to accelerate and make the majority of Iranians better off.

The economics of protesting

The 1979 revolution was run by the poor or ‘Mostazafan’. Supreme Leader Khomenei promised them to eradicate income inequalities and poverty. Iranian society felt empowered at the time by a charismatic leader and his promises. But these ultimately turned out to be empty, at least in the economic sense. Today, Iran’s political system does not apply modern science to the management of its economy. Instead, it uses a dominant public sector to redistribute economic rents to loyalists, among other things. This ensures survival of Iran’s political system but does little to achieve a more equal distribution of income and wealth. Such a system is, however, incapable of identifying and implementing effective solutions to overcome modern challenges such as COVID-19, or society’s desire to think and live more freely as expressed in the ‘women-life-freedom’ movement. Force thus becomes the currency of regime survival in the face of protests and social unrest. However, as livelihoods deteriorate, Iran’s ruling elites will not be able to maintain their positive spin on the actual state of the economy, which is set on a negative trajectory. If modern media pull Iranian civil society into activism, economic hardship pushes them into the same direction.

Stay tuned for the next blog. Subscribe to our Middle East Updates.