Spring blossoms in Jordan, but what is next?

Whoever thought the Arab Spring was over should look again, and this time to Jordan. The reasons why people were protesting in 2011 have only become more pressing. Years of economic mismanagement, political exclusion, and regional instability have brought Jordan to the verge of breakdown. The IMF-backed economic changes that King Abdullah proposed brought thousands of Jordanians to the streets to protest. Despite the recent Gulf pledge of USD 2.5 billion to patch up Jordan’s public finances, he faces an increasingly stark choice between meaningful and comprehensive reform – or repression.

The Jordanian economy is not doing well. Unemployment stands at 18.5%,[1] and some expect it to grow further.[2] Inflation jumped from -0.8% to 3.3% in a year, and GDP growth was 2.1% over 2017.[3] The country has a national debt equivalent to 95% of its GDP.[4] Crucially, Jordan remains much too dependent on other states to balance its accounts. While part of Jordan’s current economic difficulties can be explained by the regional situation, much is the result of a decades-long refusal to initiate broad economic and political reform.

It is not like reform was never tried. When King Abdullah inherited his throne in 1999, he kickstarted an ambitious economic reform agenda. Unfortunately, much of it was blocked by the Jordanian tribes, as were most further attempts. These ‘East Bank’ tribes form the core of Jordan’s original population. In contrast, the country’s ‘West Bank’ Palestinians were later arrivals, as they crossed the Jordan river in large numbers in the late 40s, 50s and 60s. The tribes have long benefited from an arrangement that trades political loyalty for economic advantage. More precisely, in return for their loyal support to the continued rule of the country’s Hashemite monarchy, Jordan’s tribes have enjoyed significant political influence and economic perks, including thousands of jobs for life in a bloated public sector.

(...) in return for their loyal support to the continued rule of the country’s Hashemite monarchy, Jordan’s tribes have enjoyed significant political influence and economic perks

A key feature of this arrangement is that it is largely financed through foreign largesse. Countries like the US and Jordan’s Gulf neighbors have long kept Jordan’s public finances afloat with aid and oil money. These, in effect, ‘buy’ Jordan’s stability in a conflict- and crisis-prone region.[5] The short of the matter is that Jordan’s economic model is not self-sustaining but that its political settlement is highly dependent on predictable and continuous foreign finance. The main domestic consequence of this arrangement is that the Jordanian economy has increasingly reinforced royal as well as ‘East Bank’ privileges and social status. Growth has remained sluggish.[6]

In face of the current public finance crunch, the Jordanian King proposed IMF-supported tax reforms to increase state revenues and pay off the national debt. This is a classic from the IMF script: more tax revenue will reduce Jordan’s deficit and re-establish macro-economic stability with less dependence on international donors. Yet, such measures also hit middle class and poor Jordanians hard, for example by doubling bread and fuel prices. There are observers, such as The Economist, that believe these reforms are a good solution to Jordan’s economic problems and its international dependence.[7] The fact that only 3% of Jordanians pay income tax is often noted in support of this line of argument.

These observers might be right in economic terms. However, they overlook the fact that 3% is also the amount of influence most Jordanians have on their country’s political system and its decision-making processes. Any tax-reform, however necessary, will not change the highly restrictive nature of this system. The Jordanian government is appointed by the King, as is the Prime Minister. There is a democratically elected parliament, but it has no power and is barely representative. Jordanian ‘West Bank Palestinians’, in fact the majority in a population of 7 million, are particularly poorly represented. Jordan hardly has any political parties and parliamentary seats are distributed in such a way that the tribes always win a majority. When parliament gets to vote, its members usually ‘get a phone call’ from the Royal Court with instructions. Although the political exclusion of Jordan’s Palestinians has always been a trigger of societal unrest, the recent protests suggest that economic reform at the cost of the politically marginalized will also be a hard act to pull off.

Ultimately, the question is what kind of stability the King wants to retain. If it is the kind that entails positive change and growth, political reform must happen before (or at least in tandem with) a comprehensive economic reform package that spreads the pain more evenly than the IMF-backed tax reforms. In fact, such a reform package already exists in the form of the National Agenda - an extensive reform plan that was developed on royal orders years ago, but (again) blocked by the tribes. Many of the plan’s elements remain relevant and can still be implemented with minor updates.

First and foremost, the King should allow the formation of political parties, and grant the press greater freedom so that a civic space can slowly develop. At some point, this should be followed by a new electoral law that ensures political parties have a fair shot at winning seats in parliament. In a bid to avoid alienating the tribes, some seats could remain reserved. Finally, in a decade or so from now, an elected government and prime minister could exercise power independently of the King, who might retain several royal prerogatives on key social and political issues.

First and foremost, the King should allow the formation of political parties, and grant the press greater freedom so that a civic space can slowly develop

Economic reform should focus on creating a better connection between labor market supply and demand, progressing educational reform, supporting private entrepreneurship (youth in particular) and easing credit conditions for start-ups. Incentives to increase female participation are also high on the list of economic growth enhancing measures. Today, only 15% of Jordanian women are employed.[8]

In a sense, the protests present King Abdullah with a perfect excuse to sweep the dust of the National Agenda. The thousands of Jordanians that demonstrated peacefully are a rather compelling rationale for both the King and the tribal elites to undertake meaningful reform in a gradual but controlled manner. Mindful of the events of 2011 in Yemen or Egypt, they might reduce the risk of greater political unrest that could lead to crisis or revolution. So far, none of the political decisions made since the protests started have altered the need for comprehensive reform: not the provisional freeze of the IMF-backed tax reform, not the cosmetic change in government, and not the temporary bail-out by the Gulf states. All three are postponement tactics that may slow, but are unlikely to stop growing dissatisfaction among the Jordanian people, or to solve the state’s economic problems in the long run.[9]

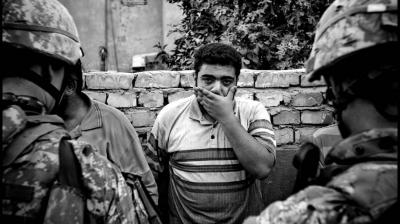

Still, several Arab countries have been at this point before, and few of them have chosen gradual reform. Indeed, the other option to maintain stability is of the Egyptian variety. In that case, exclusion and repression will continue and possibly get worse. The Jordanian security services are renowned for their intelligence and professionalism, and so far, political activity remains tightly controlled. If anything, the Gulf’s aid package indicates Jordan’s neighbors are more than willing to keep the King in the saddle, given the regional context. The same can probably be said about the US and Israel. Yet, there are strong indications that the King himself sees the need for political reform in principle. I interviewed many of the King’s former ministers, Royal Court officials, and childhood friends. Many of them believe he actually prefers an English-style constitutional monarchy. The difficulty is, of course, how to transition to one without too much violence or socio-political breakdown.

One thing is certain, Jordan’s political order approaches a tipping point that will initiate a new phase of the Hashemite Kingdom’s existence

Either scenario will have profound consequences for the region. A slowly democratizing Jordan could inspire Iraqi’s, Palestinians and Moroccans alike. It could stimulate Sunni West-Iraq by providing a model for positive political engagement, or even create long-term pressures on finding a resolution for the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. For the citizens of Morocco or the Gulf, it could show the possibility of peaceful transition to less monarchical rule without rendering the monarchy less relevant. On the other hand, an increasingly repressive Jordan would further squeeze its ‘West-Bank Palestinians’ and create another high-pressure vat waiting to explode.

One thing is certain, Jordan’s political order approaches a tipping point that will initiate a new phase of the Hashemite Kingdom’s existence and its place in the region, for better or for worse.

This analysis was written for Clingendael's Levant research programme to complement its analysis of regional geopolitics. The results of this research program can be accessed here.

Violet Benneker is a PhD candidate and lecturer at the Institute of Political Science at Leiden University. Formerly based in Amman, she researches elites’ human rights decision-making in Jordan. She teaches her own master’s course ‘The Politics of Human Rights’.

[2] http://jordantimes.com/news/local/unemployment-rate-remains-185-last-quarter-2017; http://jordantimes.com/news/local/unemployment-rise-near-future-due-wrong-policies-%E2%80%98

[4] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/06/jordanians-vow-continue-protests-demand-approach-180604125104346.html