The EU and most EU member states are disillusioned by Russia, even to the point of feeling betrayed. Brussels always saw the EU–Russian strategic partnership as more than an economic relationship comprising the exchange of Russian energy for EU-made machinery. Instead, the EU’s aim was to establish a process of normative rapprochement, based on openness, dialogue and modernization. The expected end-result was supposed to be a stable, satisfied and ‘European’ Russia that is truly deserving of the label ‘strategic partner’. After more than a decade of highly institutionalized ties and biannual high-level summits, negotiations on a new EU–Russia Agreement were finally suspended; the last acrimonious meeting took place in Brussels on 28 January 2014.

Although the Ukraine crisis came as a surprise, the breakdown of EU–Russia ties had developed in slow motion, ever since the much-advertised Partnership for Modernization was launched at the 2010 Rostov Summit. The ambition of cooperation on a wide range of policy areas – from research and education to culture, and from human rights to energy governance – remained declarative. The return of Vladimir Putin (who began his third term as Russia’s President in September 2011) implied the end of a more forward-looking model of modernization (under President Dmitry Medvedev). Instead, President Putin adopted a foreign policy based on Realism and even neo-revisionism, in the hope that a rekindled process of Eurasian integration would halt the encroachment of the EU and NATO into Russia’s ‘near abroad’. The EU’s reluctance to liberalize its strict visa regime to include ordinary Russians (and not just businessmen, researchers and diplomats) proved a major bone of contention and ‘has helped the authorities to portray the EU negatively inside Russia’.[12] Moscow also withdrew from the Partnership for Modernization’s human rights dialogue, to the EU’s dismay. In 2013, the EU–Russia ‘strategic partnership’ had already become a misnomer. In May 2015, the European Parliament officially pulled the plug by declaring that Russia ‘can no longer be treated as, or considered, a “strategic partner”‘.[13]

Official EU policy (March 2015) is based on the premise that ‘restrictive measures against the Russian Federation […] should be clearly linked to the complete implementation of the Minsk agreements. […] The European Council does not recognize and continues to condemn the illegal annexation of Crimea and Sevastopol by the Russian Federation and will remain committed to fully implement its non-recognition policy’.[14] This unequivocal stance quickly became the mantra within all of the EU member states. Dutch Minister of Foreign Affairs Bert Koenders echoed this official statement in September 2015: ‘Sanctions remain necessary while Russia refuses to implement the Minsk agreements to resolve the conflict in eastern Ukraine. There is also a separate set of sanctions for Crimea, which will remain in place as long as Russia continues its illegal annexation’.[15] This stands in stark contrast to President Putin’s statement in March 2014 that ‘Crimea is our common historical legacy and a very important factor in regional stability. And this strategic territory should be part of a strong and stable sovereignty, which today can only be Russian’.[16] On the future of Crimea, the EU and Russia are clearly at loggerheads. Policy-makers on both sides have formulated their positions in tough, uncompromising terms, making it hard to see room for flexibility and a diplomatic trajectory towards the ‘middle ground’.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Although the EU celebrates its united front against Russia as a major achievement, its main challenge is recalibrating policy vis-à-vis Russia, opening up political room for manoeuvre.

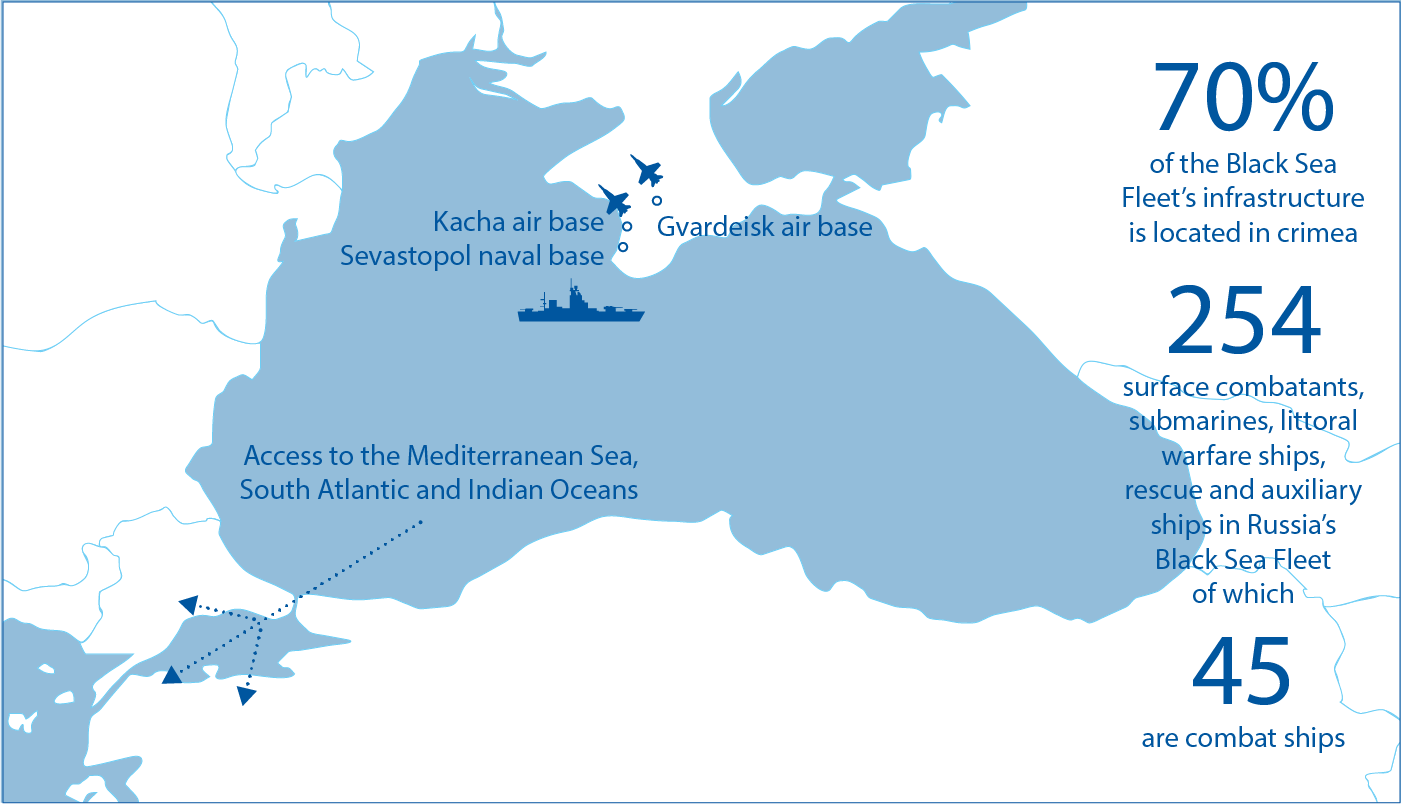

The EU is not the only Western antagonist of Russia, but coordinates its policies with the United States, and to a lesser extent (within) NATO and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). Flexible configurations like the so-called ‘Normandy Format’ (comprising Germany, France, Ukraine and Russia) also play a role. Still, the EU has turned itself into the key player in the region, which means that the onus for finding a possible way out of the current dead-end street is put on Brussels. Although the EU celebrates its united front against Russia as a major achievement, its main challenge is recalibrating policy vis-à-vis Russia, opening up political room for manoeuvre. For Russia, it will be easier to budge on eastern Ukraine than on Crimea, simply because its naval base in Sevastopol and the Black Sea Fleet remain crucial because of their size, location and infrastructure (see figure 2). Crimea gives Russia access to its naval base at Sevastopol, home to the Black Sea Fleet (BSF). Operating from Sevastopol, Russia has the ability to project power in and around the Black Sea and also provides the Russian Navy with access to the Mediterranean, and to the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans. Crimea also serves as headquarters for Russia’s newly constituted Mediterranean Task Force, which has recently resumed permanent operations in the eastern Mediterranean, extending Russia’s reach and enhancing its prestige in the region. The Mediterranean Task Force was recently used to deliver military equipment to Syria, to remove Syrian chemical weapons and to conduct anti-piracy operations near Somalia. Crimea is also home to the BSF 11th Coastal Defence Missile Brigade, and is part of a new system of advanced combat aircraft stationed at Crimea’s Kacha and Gvardeisk air bases, which will significantly enhance Russia’s air defence capabilities on its southern flank.[17] Since Russia’s official lease of Sevastopol (from Ukraine, running through 2042) was put into doubt by Ukraine’s government in Kiev,[18] Moscow saw itself ‘obliged’ to take over the Crimean Peninsula, which it did in March 2014.

Many EU leaders argue that a ‘prosperous, stable and democratic Ukraine is vital to Europe’.[19] What is more, the EU’s self-styled role as guardian of ‘European norms and values’ makes it nigh impossible to water down its demands. So how can this Gordian knot be loosened and ultimately untied?