EU policies

To address the issue of irregular migration, the EU has adopted a complex and multifaceted response, now loosely organised under the 2015 European Agenda on Migration.[12] The Agenda contains four pillars that focus on 1) reducing the incentives for irregular migration, 2) improving border control, 3) developing a common EU asylum policy and 4) strengthening legal migration. The ‘irregular migration’ pillar comprises a diverse set of measures and projects, such as more traditional development measures that aim to address the root causes behind irregular migration, securitised measures that focus on the dismantling of smuggling and trafficking actions, and migration management measures that seek to improve return policies and shelter in the region of origin.

This multi-faceted approach is also visible in the more specific EU migration policies targeting the African region. The EU is building on the 2015 Valletta Agreement to implement its Agenda on Migration in Africa. The Agreement’s key areas are: 1) addressing the root causes of migration; 2) enhancing the protection of migrants and asylum seekers through maritime operations; 3) tackling the exploitation and trafficking of migrants; 4) improving cooperation on return and readmission; and 5) establishing and organising legal migration channels.[13] In June 2016, the EU launched a Partnership Framework to further mobilise and focus EU actions in these areas. Under the Framework, the EU agrees on tailored ‘compacts’ with third countries that outline ‘financial support and development and neighbourhood policy tools [that] will reinforce local capacity-building, including for border control, asylum procedures, counter-smuggling and reintegration efforts’.[14] In addition, the EU Action Plan against migrant smuggling (2015-2020) implements the ‘fight against migrant smuggling as an [EU] priority’. [15]

The EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa funds a substantial part of the EU Partnership Framework. This Trust fund, set up to address the root causes of migration, finances projects that create employment opportunities, support basic services for local populations and support improvements in overall governance, as well as projects that improve migration management.[16] In addition, the EU created the European External Investment Plan ‘to promote sustainable investment [in Africa and the Neighbourhood] and tackle some of the root causes of migration.’[17] Despite this focus on development, stemming irregular migration and strengthening borders are key drivers of spending. The European Commission even goes as far as to say, for example, that ‘a mix of positive and negative incentives will be integrated into the EU's development and trade policies to reward those countries willing to cooperate effectively with the EU on migration management and ensure there are consequences for those who refuse’.[18]

As a consequence, many of the policies outlined above have a strong emphasis on security measures such as anti-smuggling operations and border control.[19] Similarly, some of the most visible programmes that have resulted from the Valletta agreement are security measures aimed at disrupting human smuggling networks operating out of Libya (EU NAVFOR MED Operation Sophia) and on capacity building to help the Nigerien authorities prevent irregular migration and combat associated crimes (EUCAP SAHEL Niger mission).[20] Technical and securitised migratory management has thereby become the main driver of development spending in the region. In the process, concerns about the relationship between irregular migration and regional (in)stability, and the way in which migration-mitigating measures might influence this relationship, have taken a backseat in favour of short-term results. It is precisely the lack of attention to the politics of irregular migration in a region that is already very conflictive and instable to begin with that can be expected to contribute to these policies’ ineffectiveness in the medium to long term (see Annex 2 for this relationship).[21]

Intra-African migration: historical legacies and contemporary practices

The historical legacies that drive contemporary trans-Saharan migrations illustrate that the potential for destabilisation is indeed an issue to be reckoned with. Trans-Saharan migration is an age-old phenomenon that can only be understood in the context of the tightly interwoven geographic, cultural and economic patchwork that constitutes the larger Sahel and Sahara region. Post-colonial arrangements have created independent states whose borders cut through tribes, clans and ethnic groups. These groups generally constitute a minority within the three countries at issue here, and a disadvantaged political and economic minority located on the desert’s fringes at that. Governments historically paid little attention to the social and economic development of these regions and their communities and, in the cases of Mali and Libya, even played the different tribes and clans off against one another.[22]

To deal with the region’s climatic challenges, such as variations in rainfall, cyclical drought and growing desertification, the pastoral and sedentary communities in the Sahara and Sahel relied – and continue to rely – on various coping strategies. Internal and cross-border migration between communities across the region served to dampen the harshest shocks to people’s livelihoods.[23] This was the case in particular for Niger, which ‘long depended on neighbouring economies as a source of employment’, as a result of which ‘all of its neighbours house significant populations from the Nigerien diaspora’.[24] Looking for economic opportunities or seeking refuge in response to climatic challenges, Malian populations similarly settled temporarily in neighbouring countries such as Niger, Algeria, Burkina Faso, Mauritania and Libya.[25]

Libya and Algeria became particularly attractive destination countries due to their strong economies. Commercial ties that had developed over the years between southern Algeria and northern Mali saw many Malian traders and seasonal workers cross the Algerian border to find work there.[26] Algeria and Mali even formalised this migration through bilateral agreements that legalised free movement between the two countries.[27] As for Libya, its oil reserves are the largest in Africa and the country’s relative wealth has long attracted migrants in search of work. In addition, Qadhafi’s policy of pan-Africanism resulted, among other things, in an open door policy whereby African nationals were allowed to enter Libya without visas between 1998 and 2007.[28] Sub-Saharan Africans flocked to Libya in large numbers to work in agriculture, construction and other menial labour such as cleaning.[29]

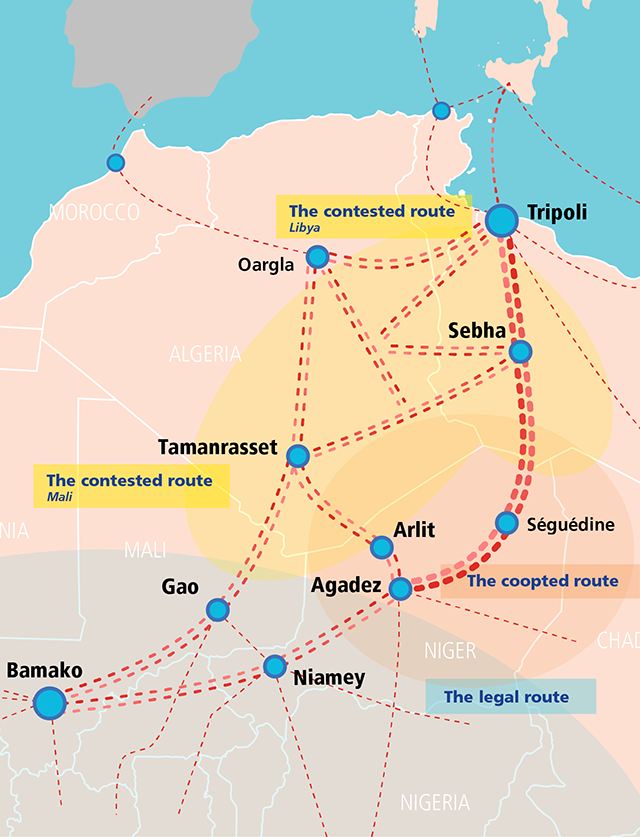

The role of Algeria and Libya as migrant destination countries remains visible to the present day. Figure 1 (below) provides an overview of the main trans-Saharan migration roads servicing the West-Central Mediterranean route. Migrants that travel this route come from West African countries, such as Nigeria, Guinea and Ivory Coast, or from Mali and Niger itself. The northern Nigerien desert town of Agadez forms the main migration hub on this trajectory. IOM estimates suggest that in 2016 alone some 310,000 migrants will travel from Agadez to Libya, while an additional 30,000 migrants will travel from Agadez to Algeria.[30] Gao in Mali is a somewhat smaller hub, with some 30,000 to 40,000 migrants estimated to travel from Gao to Algeria in 2016.[31] This is quite surprising, as it means that the ongoing internal conflict in northern Mali has not stopped transit migration. From Gao and Agadez, migrants generally travel on to Sebha in Libya or Tamanrasset in Algeria. These transit hubs form staging points for migrants seeking temporary labour in the region as well as for migrants that choose or are forced to travel further north to the coastal area and/or Europe.

Click on the highlighted areas for more detail

Contemporary fearmongering holds that scores of African migrants ‘lie in wait in Libya, ready to break for Europe’.[32] The majority of migrants travelling the trans-Saharan route self-report, however, that Algeria and Libya are their final destinations. In comparison, only 20 percent to 35 percent of migrants initially report that they intend to travel on to Europe.[33] Although these figures are based on self-reporting, with all the methodological flaws this entails, these percentages are in line with a historical pattern in which, based on the numbers of returnees by land, only ten to twenty per cent of migrants have been found to travel on to Europe.[34] The UNHCR data in Box 1 below outline that this continues to be the case in the current day and age, as the figure of 71,000 West Africans arriving in Italy corresponds to 22.9 percent of the 310,000 migrants reportedly transiting through Niger this year.[35] This is some ten percent less than the 106,000 migrants that travelled back from Libya to Agadez in 2016.

|

2015 |

2016 (to Sep) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Nigeria |

14.5% |

Nigeria |

20.6% |

|||

|

Gambia |

5.5% |

Gambia |

6.6% |

|||

|

Senegal |

3.9% |

Ivory Coast |

6.6% |

|||

|

Mali |

3.8% |

Guinea |

6.6% |

|||

|

Ghana |

2.9% |

Mali |

5.3% |

|||

|

Ivory Coast |

2.5% |

Senegal |

5.2% |

|||

|

Guinea |

1.7% |

Ghana |

3.1% |

|||

|

Total arrivals in Italy |

153,842 |

132,043 |

||||

|

West Africa total |

34.8% |

(53,330) |

54.0% |

(71.303) |

||

|

Total migrants Niger Libya (to Nov) |

311,036 |

|||||

|

Compare: West-African arrivals in Italy as a percentage |

22.9% |

(71,303) |

||||

|

Compare: West-African migrants returning from Libya to Agadez |

34.1% |

(106,154) |

||||

Source: Nationality of arrivals to Greece, Italy and Spain – Monthly – Jan to Sep 2016, UNHCR, Geneva, link (accessed November 2016). Monthly Sea Arrivals to Italy and Malta – Jan to Dec 2015, UNHCR, Geneva, link (accessed November 2016). Statistical Report Niger Flow Monitoring Points (FMP) 01 Nov – 30 Nov 2016, IOM, Geneva, 2016, link (accessed December 2016).

These figures go to show that the reality of African irregular migration is much more complex than often assumed, with Nigerian-based human trafficking networks, seasonal intra-African cross-border migration, West African economic migrants and even Syrian refugees all travelling the same route.[36] The conspicuous absence among the Italian arrivals of Nigeriens – the largest group of migrants departing for Algeria and Libya from northern Niger – underlines that not all migrants should necessarily be conflated into intercontinental migrants. In a similar vein, a 2014 study on migration conducted by the Malian Ministry of Overseas Malians concluded that the majority of Malians abroad seek opportunities in emerging economies on the continent and that fewer are entering Europe.[37] This suggests that the majority of migrants travelling the trans-Saharan route maintain traditional, circular migration patterns in search of temporary labour. At the same time, and as will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 5 below, the hardened migration climate in the region combined with practices of migrant exploitation in Libya also forces migrants to travel on to Europe – even if they never intended to go there in the first place.

A better understanding is thus needed of the factors and circumstances that incentivise or disincentivise migrants to pursue their journey all the way to Europe. This would make it possible to distinguish between different migratory streams and to safeguard intra-African migration. This is crucial for stability purposes, as intra-African migration will likely become an all the more salient coping strategy in the near future. In the short term, this is the case because the lean season with little or no harvest has reportedly increased, while irregular rains affect the agricultural sectors.[38] For many people, migration is truly an escape valve in the face of diminished livelihoods. In the long term, climate change, population growth and youth unemployment may increase pressure on local communities. The danger currently exists that these relatively benign coping mechanisms will get caught up in measures that aim to stop all migration.[39] In a region that is already rife with political and social instability, the failure to recognise that intra-regional migration relieves tensions on overburdened communities adds fuel to an explosive mix.

Policy recommendation 1: understanding trans-Saharan migration

Understanding this diversity of trans-Saharan migration, as well as its stabilising nature, provides policy makers with crucial knowledge that could help them design more efficient and effective policies. To date, the EU has set itself the needlessly over-ambitious goals of addressing the root causes of all intra-African migration and of seeking to manage all flows. In light of the multitude of migratory streams that constitute trans-Saharan irregular migration, a vital precondition for efficient and conflict-sensitive responses to trans-Saharan migration is thus to understand more clearly which migratory streams end up in Europe – and to develop policies that target these streams only while regularising the streams that constitute intra-African coping mechanisms instead. An added benefit of this approach is that it would likely be much more efficient to target specific streams rather than irregular migration as a whole. To this end, the following recommendations apply:

Existing data sources should be combined in an overarching database that provides information on migratory dynamics. The IOM and UNHCR have made important strides in collecting data on transit migration and the migrants arriving in Europe respectively. The dynamics behind these streams should be further disentangled through use of the data collected through Frontex migrant interviews, as well as domestic information sources such as the Dutch Immigration and Naturalisation Service (IND) and academic sources.[40] Policy makers should use this database to gain a better understanding of the factors and circumstances that incentivise or disincentivise migrants to pursue their journey all the way to Europe.

Policy makers should adopt more tailored approaches tackling the root causes of migration in relevant migrant origin and transit hubs based on the information collected in the step described above. In addition, these tailored approaches should focus on the regularisation of common intra-African streams, such as by issuing civil registry cards to communities that frequently circulate across borders. Formalising and legalising part of the current practice will help understand, map and organise migration so that it can be better managed – accepting that circular intra-African migration is a timeless and unstoppable phenomenon.

In the long term, incentives should be created to improve intra-African migration in a manner that regularises regional mobility, and that contributes to regional economic development. In this sense, one may think of financial or trade incentives to urge stable North and West African countries to adopt favourable policies towards economic migrants. In a similar vein, the current focus on migration provides a unique opportunity to increase EU collaboration with ECOWAS to further strengthen its free movement protocol and intra-regional trade structure. Investments in credible regional economic opportunities would likely reduce the migratory pressure towards the EU.