In general, the customary justice mechanisms of Gao, Mopti and Tombouctou have similar processes. Typically in response to disputes over land, inheritance, theft or marital issues, individuals will ask customary leaders for help, either to determine a fair result or to act as a mediator between parties. These leaders tend to be men who have an important role in their communities (such as a village or community chief), a religious figure (such as an imam, marabout or qadi) or a traditional communicator (such as a griot). The oldest people in the community, sometimes referred to as sages, are also often approached to take on this role. With the exception of religious leaders, training could either be nonexistent or based on observing the customary leaders that came before them.

The typical conflict resolution process starts at the level of a family discussion, then moves to a discussion between friends, then neighbours, then the neighbourhood and successively to the village. Most respondents try to keep disputes from being dealt with outside of the village level because of a preference that ‘dirty linen be washed in the family.’

When called upon, a customary leader will generally speak with both sides, consult witnesses, and allow each side to confront each other. The leader’s decision is usually publicly made and can be influenced by the input or vote of a council of advisers, a religious text or the community’s traditions. The decisions are not legally binding but are enforced given the perceived moral authority of the customary leader.

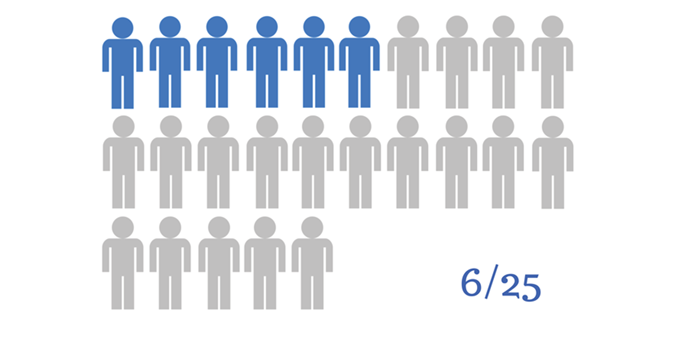

The origin of these traditions is unknown, but many believe that they predate the colonial era. Customary justice mechanisms are free of charge, easily accessible and seen as being more efficient than the formal justice system. However, many respondents also explained that customary justice decision-making processes can take longer than formal justice processes to allow the time needed to find a resolution that restores societal harmony, not just one that proclaims a winner. Customary justice leaders typically do not make a written record of their decisions, which is perceived as weakening their enforceability. Collaboration between the customary and formal justice systems is somewhat typical, and is welcome to the extent that this prevents multiple or contradictory decisions on the same issue. Of the 25 customary justice leaders who indicated whether they collaborate with the formal justice system, only six (24 percent) answered affirmatively (figure 4).

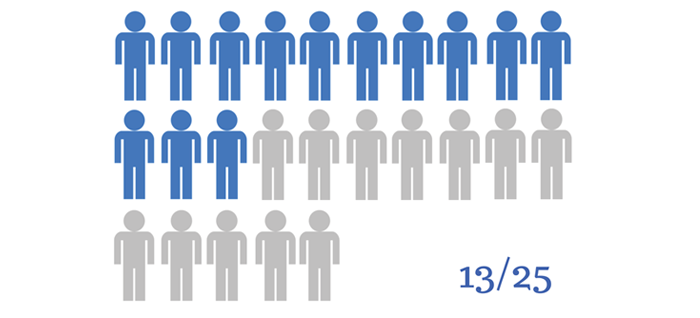

Thirteen customary justice leaders, or 52 percent of those who answered the question, explained that in the future they would like to collaborate more with the formal justice system (figure 5). Reasons include wanting to create a reliable system of precedence, to improve their knowledge and abilities in dispute mediation and to create a better articulation between what should be handled by customary justice rather than by formal justice. Customary justice leaders who do not wish to collaborate more with formal justice gave several reasons including that the actors of the formal system are too corrupt, that the formal justice actors are too pretentious and ‘not from our society’ and that they are too ‘aged’ to do so.

The customary leaders interviewed handle a wide-ranging array of disputes, some taking on multiple cases every week, others only several cases a year. They will not necessarily take on every conflict, some specifying witchcraft, serious crimes and boundary disputes as being more suited for resolution by the formal justice system. For the most part, customary leaders do not fear any repercussions from their involvement in disputes because they are speaking ‘the truth,’ and because they take decisions collectively while acting in the interest of the greater community.

The majority of those interviewed spoke in favour of the continual usage of customary justice and indicated a general sense that customary leaders were a good first port of call to resolve disputes.[4] Many explained that even if they disagreed with a decision, they still believed that it should be followed because it was made for the good of the community. Those who disagreed with a customary justice ruling and decided to take their dispute to the formal justice system seemed to be able to do so without any trouble.

Infographics depiciting the unique features of the customary justice mechanisms in Tombouctou, Niafunké, Gao, Ansongo, Mopti, and Douentza are interspersed throughout the report.