Geopolitical tensions in western Iraqi Kurdistan

Geopolitical limelight on the Middle East tends to focus on Iranian-Saudi rivalry, recently intensified by the US quitting the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), and the Syrian civil war. However, these primary conflicts obscure several secondary drivers of instability in the Middle East, such as the longstanding Palestinian and Kurdish questions, Turkish-Iranian rivalry and Turkish-Iraqi tensions. It is in northwestern Iraqi Kurdistan that primary and secondary drivers of geopolitical instability increasingly interact, namely the Kurdish question, the Syrian civil war and Iran vs. Turkey rivalry.

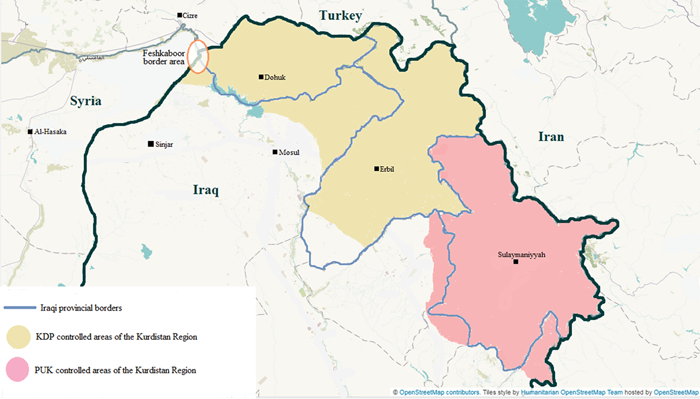

Western Iraqi Kurdistan is traditionally a stronghold of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) with the Dohuk governorate at its core (see Figure 1). However, the area also connects both the interests and military presence of Turkey, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK)[5] and Iran (by proxy), which are largely competitive in nature. For starters, the presence of the PKK in western Iraqi Kurdistan has become more pervasive over the past few years. This has taken the form of military activity and an increase in popular sympathy for the group. Some suggest that the PKK might yet establish a political party in the area.[6] For several reasons, the KDP perceives this development as a potential threat. First, the KDP aspires to lead the Kurdish cause itself. Second, the PKK maintains close ties with the PUK, Iran and the Syrian Democratic Union Party (PYD – a Syrian Kurdish outfit with its own armed group, the People’s Protection Units (YPG) – while the KDP itself must maintain good relations with Turkey as its main economic lifeline. However, Turkey is implacably opposed to both the PKK and PYD, which it considers closely-linked terrorist organisations.[7] It is in part for this reason that the KDP has allowed Turkish forces to operate from bases located on its territory, despite Baghdad’s protestations. Although the Iraqi government regularly condemns Turkish military activity and bases in the Dohuk and Soran areas as violations of its sovereignty, the Turkish military presence in Dohuk has remained significant. In Turkey’s view, it pursues a vital national security interest by taking its fight against the PKK closer to the latter’s home turf and by creating a buffer between southeastern Turkey and the PKK’s Iraqi bases, much as in Syria’s Afrin.[8]

The provinces of Dohuk, Erbil and Sulaymaniyyah officially form the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) along the lines of the administrative boundaries denoted in blue above. Actual Kurdish territorial control (excluding the disputed territories) extends beyond the administrative boundaries in most places save one.

The Feshkaboor border area in Dohuk governorate offers a microcosm of the interests at stake as it is here that the borders of Syria, Turkey and Iraq meet. In consequence, it is a major transit point for licit and illicit goods, such as oil and contraband, as well as people – from businessmen and traders to PKK fighters. It connects, for example, the Syrian YPG with the Iraq-based ‘Turkish’ PKK, as well as the PKK with its constituents and guerrilla activities in southern Turkey. If there is a Kurdish equivalent to the ‘Shi’a land bridge’ from Tehran to Beirut, it is here. When Iraqi forces sought to establish control over the area after the referendum, Kurdish politicians/forces and their Arab equivalents traded both accusations and bullets for a few days. Although today Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) control the actual border crossing, the area is sparsely populated and rugged, making effective surveillance difficult.[9]

Further afield, but still close to Dohuk, is the matter of influence and control of the Sinjar area, which connects PKK activity in Dohuk and Sulaymaniyyah with Syria. When the KDP Peshmerga[10] withdrew from these lands in the face of the IS’ 2014 onslaught, the PKK opened a corridor for the Yezidi population to flee and then fought the IS over Sinjar. Later, after the defeat of IS, PKK forces were initially reluctant to leave, even under serious pressure from the Iraqi government, as Sinjar is part of the longer, alternative route between the Qandil mountain range in northeastern Iraq – the PKK’s main base – and the Syrian Kurdish territories of the PYD/YPG. When the PKK finally did leave Sinjar in late March 2018, it strengthened the Sinjar Resistance Units (YBS). [11] And, by having these Units qualify for registration under the umbrella of the Iraqi Hashd al-Sha’abi, the PKK in a sense also managed to retain a presence.[12] As both the PKK and significant parts of the Hashd have close connections with Iran, some even think the YBS are a soft proxy of the PKK, which has Iran’s tacit approval.[13] While this line of thinking may underplay the evident urgency with which Iraqi Yezidi communities had to protect themselves from IS, and thus downplays the agency of the YBS, it is a possibility that must be reckoned with.

This mix of PKK, KDP Peshmerga, Turkish, Yezidi and Iraqi forces – and associated geopolitical tensions – in western Iraqi Kurdistan will not necessarily lead to violent conflict in the near future. However, its interaction with militant developments in the disputed territories (factor 2) or popular dissatisfaction with the KDP in Dohuk governorate (factor 3) could intensify and gradually create the elements of a greater crisis.

| Elements of restraint |

Developments to monitor |

Trigger events |

|---|---|---|

| Joint Iraqi-Turkish operations against the PKK are unlikely due to Iraqi-Turkish animosity[14] |

The intensity and pace of Turkish military operations in Dohuk governorate (including the possibility of Turkey initiating an offensive in the Qandil mountain range) |

The ISF using control over the Feshkaboor crossing to enforce fees from oil sales being paid directly to Baghdad[15] |

| The KDP needs to stay on reasonable terms with Turkey, the PKK and the PYD |

KDP-PKK relations: rhetoric and (potentially) violent clashes |

The creation of a PKK-affiliated political party in/around Dohuk |