The material realities and perceptions of Gulf Arab aid, investment and trade into African states cannot be understood without factoring in the long and deep history of ambivalent relations between the Arabian Peninsula and the Horn of Africa. The societies of the Gulf have profoundly influenced the economic, political and sociocultural landscape of the Horn of Africa and vice versa. From the Sinai Peninsula and the Gulf of Aqaba in the north to the strait of Bab al-Mandab and the Gulf of Aden in the south, the Red Sea is at no point wider than 355 kilometres. This geography underpins a long and deep history of relations that have often swung back and forth between intimate partnership and prejudiced animosity. Historical experiences accumulated over the centuries continue to colour how policy makers and ordinary citizens perceive each other today.

Religion is crucial in this regard. Although the monotheistic faiths had their cradle in the Middle East, northeast Africa was the site of pivotal moments in their respective traditions. It was in Egypt that Moses confronted the Pharaoh and that the Holy Family sought refuge; the legendary Kingdom of Kush, in today’s Sudan, features prominently in the Bible as the land ruled over by Noah’s grandson; the first Muslim hijra to flee persecution by the dominant Quraish tribe in Mecca was, following the instructions of the Prophet Muhammad, to Ethiopia; and the mystical union of the Jewish Prophet-King Solomon and the Ethiopian Sheba remains an enigmatic story integral to Jewish, Christian and Islamic traditions. Such narrations, fundamental to family settings and public education systems, give relationships between both sides of the Red Sea a sense of great familiarity.

Yet if religious connectivity has often represented the positive dimension to proximity, other memories — of competing imperialisms and military betrayal — are less cheerful. No old wound is more painful than the centuries of enslavement of hundreds of thousands of Africans and those of African descent across the Hejaz, the Najd, Oman and Yemen.[15] Associations between blackness and slavery remain powerful shapers of attitudes and prejudice on both sides of the Red Sea, framing perceptions of contemporary labour migration such as the Ethiopian domestic workers employed in the Gulf. Slavery was in fact only abolished in Saudi Arabia and Yemen in living memory, 1962.[16] The practice continues to exist and be tolerated in certain parts of Sudan and Yemen. In the Horn itself, patterns of cross-border labour exploitation persist, such as South Sudanese employed in Sudan and Eritreans in Djibouti, while labour migration in the other direction remains limited. Against this historic backdrop, complexion continues to serve as an important, though contextual, marker of social position.

The movement of ideas, traditions, slaves and pilgrims between the Horn and the Peninsula was for centuries complemented by a rich and well-balanced trade in food grains, salts, coffee, frankincense, livestock and much else.[17] This relative economic equilibrium between both regions was also visible in their joint subjugation by various imperial projects — most prominently those of the Ottomans and the British — which cut some of the interregional links that had grown organically in the past yet stimulated intensified interactions between Arabia and Africa in other ways.[18]

A shared thirst for independence and the spread of ideologies like Pan-Arabism meant that nationalist aspirations in the Middle East and northeast Africa stimulated each other.[19] Oman, Saudi Arabia and Yemen had long established statehood, the latter two after World War I, but the independence of Bahrain, Qatar and the UAE in 1971 came only a few years after that of Somalia and Kenya. Djibouti, in 1977, was the last state in the region to end European colonial rule. Many observers expected the emerging autonomous countries in both regions to be natural allies given their shared history and certain cultural similarities: Arabic is spoken on both sides of the Red Sea (recognised as one of a number of official languages in Djibouti, Eritrea, Somalia and Sudan); tastes in food and music overlap to some degree; tribal diaspora populations connect Yemen with Somalia and Kuwait and Saudi Arabia with Sudan; and the deeply religious character of all these societies could strengthen transnational solidarities and identities. Such connections do create a sense of cultural proximity, mainly in Sudan, but other competing identity markers are relevant as well, creating a substantially more complex situation in different Horn states and regions. Many groupings identify themselves more locally through complex ethnic ties, such as Somali identities in Djibouti, while religious identities may at times drive a divide between Horn and Gulf populations, such as in South Sudan.

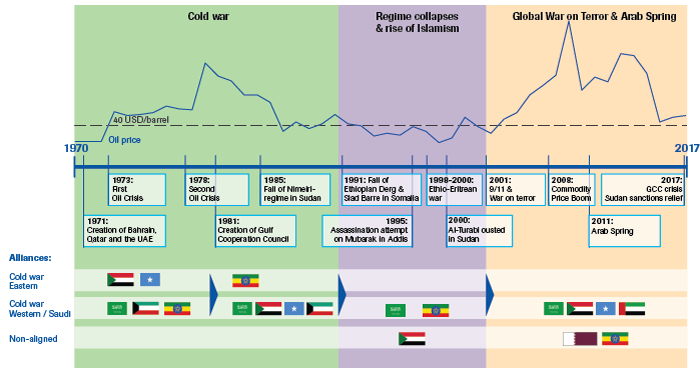

Regardless of ethnic and cultural ties, geopolitics at times played a decisive role. One macro-development that drove the region apart was the Cold War between the US and the Soviet Union, which divided the Middle East and the African continent and forced Arab and African states into different camps.[20] Shifting alliances variously pitted Egypt, Ethiopia, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, South Yemen and Sudan against each other in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. The initial period of the Cold War (1952–1970) saw Cairo, Damascus, Khartoum and Mogadishu confronting Riyadh, Kuwait, Addis Ababa and Sana’a.[21] A second phase (1977–1991) reshuffled those coalition structures in the face of regime change and changing political calculations: now Riyadh, Cairo, Khartoum and Mogadishu faced Tripoli, Aden and Addis Ababa.[22] The other decisive macro-development that shaped the international relations of the regions (with one another and with the global political economy) was the astonishing increase in the oil price in 1973: one side of the Red Sea emerged almost overnight as a global economic powerhouse, becoming the main creditor of the other side and the make-or-break patron of regimes and rebel movements in the Horn of Africa.

2.1 After Oil: The bargain between the Horn and the Peninsula since the 1970s

An oil price above USD 40 per barrel changed everything after 1973.[23] Not only did it dramatically bolster the importance of the Gulf states to the superpowers (the Gulf was the only region with which Western states ran a trade deficit, creating stagflation in the West), it also rocked the trade balance between the Peninsula and the Horn. All states on the Western shore of the Red Sea were (and are) net importers of oil, triggering balance-of-payments crises from Cairo to Mogadishu that coincided with growing economic difficulties of their own making.[24] To compensate for the acute shortfall in cash required to import daily necessities (including oil), African governments, including those in the Horn, stimulated their citizens to join the rapidly expanding labour force of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the UAE so that they could send back valuable remittances earned in the Gulf. Moreover, they also positioned themselves as deserving recipients of ODA and foreign direct investment (FDI) from the Gulf. Invoking historical, religious and cultural ties as well as underscoring that untapped agricultural potential in the interior of the Horn could help meet the growing food deficit on the Arabian Peninsula, African states sought to benefit from the growing asymmetries in wealth and power with the Gulf. Their courting of aid and investment in exchange for political loyalty and resources was a deliberate strategy that combined the need to make economic ends meet with a desire to maintain political stability.[25]

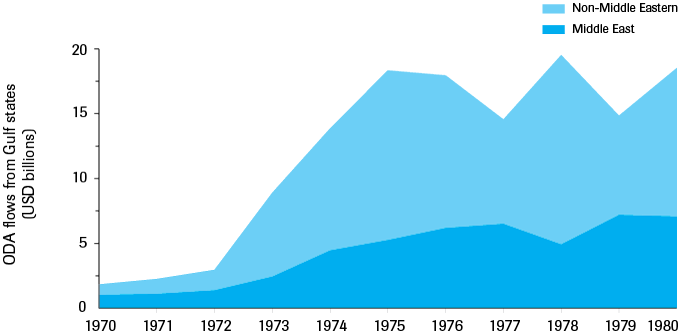

The positioning of post-independence African presidents during the Cold War was a classic case of extraversion: an intentional leveraging of limited assets — vital minerals, military bases and professed loyalty to Moscow or Washington — to attract external assistance that would help defeat internal rivals.[26] After 1973, extraversion came to define the previously relatively equal relationship between the shores of the Red Sea. Egypt, Sudan and Somalia sought Gulf patronage and sent doctors, engineers and teachers to Riyadh, Jeddah and Abu Dhabi. They pledged loyalty to Saudi Arabia in its fight against communism and spoke of informal economic union with Gulf states. For their part, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the Emirates made unprecedented sums of money available to help African states weather their balance-of-payments crises. Prior to the oil crisis, 80 percent of Gulf ODA went to other Arab countries, the Kuwait Fund for Arab Economic Development being at the centre of this generosity (see figure 3). After 1974, Kuwait began to lend hundreds of millions of dollars for special assistance to non-Arab nations in Asia and Africa for the first time. Saudi Arabia and, to a lesser extent the UAE, also established themselves along the world’s top aid donors in both absolute and per capita terms as they provided significant sums to help poorer nations deal with the rising cost of oil and imported goods. In 1977, at the Afro-Arab Conference in Anwar Sadat’s Cairo, Gulf states committed to invest USD 1.35 billion in African development projects over the next five years.[27]

It is the element of continuity between the 1970s and today that is striking. Despite continual disappointments on both sides with what this partnership actually delivered in economic terms, the key bargain — political-economic alignment between regional blocs to help manage dependence and vulnerability in turbulent international waters — has proven too valuable to abandon. Extraversion is still, as we will see, the order of the day in Gulf-Horn interactions.

Based on ‘Aid (ODA) disbursements to countries and regions [DAC2a]’ datasets of Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait. Excludes ODA disbursements made through multilateral institutions.

2.2 Confrontation and disengagement in the 1990s: Islamism and its enemies

The end of the bipolar confrontation between the US and the Soviet Union was a chasm for the geopolitics of the Red Sea as well. The oil price bubble had already burst in 1986 and thereby limited how much largesse the Gulf states could bestow on their clients, whether governments as in Somalia or Sudan or rebel movements in Eritrea, but the demise of the Socialist bloc also meant that the perceived need to do so was much less acute. The collapse of the Marxist-Leninist Derg government in Ethiopia (1991) and the disappearance of the People’s Democratic Republic of South Yemen (1990), combined with the independence of Eritrea (1991/1993), meant that the foreign policy goals of Saudi Arabia seemed to have been achieved.[28] The 1990s were a decade of disengagement from Africa by Gulf actors. The implosion of the Somali state meant that working on the ground there became more difficult — lacking a formal government serving as interlocutor and security guarantor investments in various factions continued, albeit on a smaller scale (see box 2) — and a now autonomous that Eritrea was too small and too distrustful of private-sector activity to be a major recipient of Gulf aid, investment or trade.[29] The biggest headache was Sudan, which in 1989 had witnessed an apparently traditional coup d’état by the army, but which quickly revealed itself as a front for an Islamic Revolution.

Led by the mercurial scholar and Islamist politician Sheikh Hassan Al-Turabi, the Khartoum government sought not only to fundamentally reform its domestic society and to intensify the war in Central and Southern Sudan against the rebels of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA), but also to radically restructure the international relations of both the Horn of Africa and the Middle East.[30] The military-Islamist regime was fiercely critical of the role of the US and Saudi Arabia in the Islamic world and decided to side with Saddam Hussein’s Iraq following the latter’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990 and the subsequent Gulf War.[31] Turabi invited dissidents from across the region — including Osama Bin Laden and his Al-Qaeda network, which wanted to overthrow the House of al-Saud in Riyadh and Hosni Mubarak in Cairo — and established political and security relations with Iraq and Iran, the two nemeses of King Fahd and Crown Prince Abdallah. This led the Gulf states, led by Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, to suspend nearly all aid, investment and trade relationships, public and private, with Sudan in an effort to isolate and contain Turabi (an objective shared by Ethiopia and Eritrea from 1995 onwards). In the 1990s, Sudan received only a meagre 0.5 percent (USD 0.1 billion) of pan-Arab development assistance, whereas this figure stood at 5 percent in the preceding (USD 3.6 billion) and following decade (USD 0.5 billion).[32]

Initially, this strategy appeared highly unproductive as Egyptian jihadists, with extensive backing by the Sudanese intelligence services, nearly succeeded in assassinating Mubarak during a Pan-African summit in Addis Ababa in 1995. However, the total isolation of Sudan, growing momentum for the SPLA rebellion and the financial cost of pariah status led to deep internal fissures in the military-Islamist government. In December 1999, Turabi was betrayed by his former co-conspirators and ousted from the regime he had created; power passed to Brigadier-General Omar Al-Bashir, who had since 1989 served as president but had been a mere figurehead until then.[33] Immediately, Cairo threw its political weight behind the reformed Khartoum government (reformed in the sense that Bashir announced the end to Sudan’s revolutionary foreign policy, whilst continuing to pursue its domestic agenda) and persuaded the Gulf states too to engage with the ‘new’ leadership. Sudan once again became the Gulf’s prime point of contact and engagement in the region.

2.3 So close, yet so far: Cooperation amidst disappointment and distrust in recent history

The toppling of Turabi meant, for the Gulf monarchies, the end of a directly hostile presence on the other side of the Red Sea. Even after 11 September 2001, when Saudi Arabia came under repeated attack by Al-Qaeda (including the Khobar terrorist strikes in 2004), Khartoum no longer represented a threat after well-known foreign jihadists were expelled from Sudan. Yet despite this undeniable foreign policy success, ties between Sudan and Saudi Arabia over the next decade could not be described as warm.[34] The reasons for the ambivalent relationship were similar to those for the Saudis’ lukewarm contacts with Eritrea, Ethiopia and Djibouti: from the Gulf Arab perspective, these African states were quite keen to receive external largesse but often made life difficult for Gulf investors on the ground by trapping them in a bureaucratic maze.[35] Moreover, they offered only half-hearted political support for the international causes Riyadh and Abu Dhabi deemed vital, such as isolating Iran and stopping support for Hamas in Gaza and Hezbollah in Lebanon; Sudan in particular disappointed them because it maintained important political and military contacts with Tehran. However, from the Horn perspective, it was the Gulf states that did not live up to their side of the bargain by proving fickle commercial investors and disinterested political partners, for whom Africa (like for much of the rest of the world) ranked at the bottom of their priority list. Cash-strapped, African governments have consistently signalled that they will partner with whoever is able to provide financial and other assistance for their strategies of regime survival and economic development. Ideological or sectarian preoccupations — such as the Sunni-Shia rivalry or the three-way competition between Wahhabists, secularists and Muslim Brothers at the centre of so much of Middle Eastern politics of the last two decades — are seen as costly distractions from more urgent challenges by Horn political actors.

This pattern of real cooperation and a quest for mutually beneficial economic and political ties amidst sequential disappointment and distrust persists today. Gulf states fret over large-scale migration from the Horn across the Red Sea (whether in transit to Europe or with the Arabian Peninsula as a final destination) and over the enduring close connections that Eritrea and Sudan (until very recently) maintained with Iran, Riyadh’s arch-enemy.[36] Horn states on the other hand are faced with refugees and arms-trading stemming from Yemen. Moreover, a rising Ethiopia’s challenge to Egypt’s historical hegemony in the Nile Basin — amongst other ways through the construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam — deeply concerns Saudi Arabia and the UAE, who see the stability of Egypt as critical to the regional balance of power in the greater Middle East. Egypt has historically been a gateway for Gulf Arab political and economic actors to enter the rest of Africa and, as the geographical pivot seated between North Africa, the Horn, the Levant, the Red Sea and the Arabian Peninsula, its stability directly shapes the national security of Gulf states. The presence of millions of Egyptians in other Arab countries, especially the Gulf, as guest labourers only further underlines why Egypt matters considerably to Riyadh and Abu Dhabi in particular.

For their part, most Horn of Africa societies worry about, on the one hand, the intensifying identity politics and sectarian extremism that the Gulf exports and, on the other, the pressures they face in having to choose sides in geopolitical rivalries (whether between the Gulf Arabs and Iran or amongst the Gulf Cooperation Council member states themselves) that they would rather stay out of. Djibouti, Eritrea, Somalia and Sudan know Gulf states cannot take their political allegiance for granted and thus skilfully play them off against each other for financial gain, but they know this is a dangerous game to dabble in; their fears about deepening domestic instability and inter- and intra-religious confrontation are growing. At the same time, the Arabian Peninsula is a key destination for many youngsters who send back desperately needed remittances yet who often experience profound racism and violent abuse during their sojourns in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Oman or elsewhere. Thus although the Gulf is seen as an inevitable partner with long-standing cultural and historical connections to the Horn (see figure 4 for an overview), the relation is ultimately driven by necessity rather than a shared cultural and historical legacy, as this legacy can be as divisive as it can be bonding.