Abstract: This report presents a bird’s-eye view of geo-dynamic trends in the world on the basis of 37 evidence-based indicators that reflect geo-economic, geo-political, geo-societal, geo-judicial, and geo-identitarian developments over different time periods. Our findings go against the grain of today’s conventional wisdom. In the areas where most pundits suggest doom and gloom—geo-economics, geo-military and geo-politics—we actually find more positive trends than widely recognized, especially in the most recent time periods. One possibility is that the Trump administration may actually have (unintentionally?) stumbled into a new form of hegemonic deterrence. At the same time, however, we also find robust evidence for deteriorating trends in the—far less well understood—geo-societal and geo-identitarian areas, especially from the point of view of Dutch and European preferences.

Our data for 2018 for the Netherlands paint a slightly more checkered picture than the strongly favorable one we reported on in previous years. Overall, the world still had a slightly more positive attitude towards the Netherlands in 2018 than in 2017, both in words and in deeds. But a closer look at various underlying indicators reveals a more inconsistent picture. Our data also show that the Netherlands' factual behavior has been slightly more negative towards the rest of the world in 2018 as compared to 2017 (but still in overall ‘positive’ (+0) territory). We suggest that ‘Paradise Lost’ would be too strong a trope for this trend, but that ‘Paradise Fraying’ might be more fitting.

Big events go by unseen while we sweat the smaller stuff; things happen underground while we watch the boulevard parades.”[1]

1. Introduction

An eerie sense of foreboding seems to have enveloped the world.

On the one hand, most of us just continue living our merry lives. Ten years ago, the 2008 financial meltdown caused or led to economic activity decline in half of the world countries. Today, the world economy is once again humming along, lifting ever more people out of poverty across the globe. Our own Western economies have also been benefiting from this global economic recovery. Especially those countries that were willing to put their fiscal house in order and that ensured they had better regulated and supervised banks—the Netherlands amongst them—generally suffered relatively less damage.[2] They now generate more jobs, profits, and taxes, thus giving domestic and foreign policy-makers more levers to address underlying structural weaknesses. We also read on a daily basis about new wonders of scientific-technological progress, many of which are impacting the lives of billions in various countries at an incomparably faster pace than ever before. Even politically speaking, global fundamentals are better than most recognize. Almost 60 percent of the world’s countries are now qualified as democracies, with an upward trend again in recent years. All the while, the international order(s) still stand(s)—international organizations function, diplomats negotiate, agreements are made.

And yet...

In the 2018 world Economic Forum’s Global Risk Monitor, leading experts and decision-makers from various countries conveyed elevated levels of concern about risk trajectories in 2018, particularly with respect to geo-political tensions.[3] Not only ‘the elites’ exuded doom and gloom, however. Average citizens attitude across the world also proved more negative than at any time since 2005, according to a Gallup poll tracking the feelings and emotions of over 154,000 people in more than 145 countries: "Collectively, the world is more stressed, worried, sad and in pain today than we have ever seen it,"[4] is how the study summarized its findings. The dawning realization that the President of the United States seems to question many of political and economic foundations of the post-World War II international order, both institutionally and conceptually (as well as in terms of decorum); that the US’ still unique position in the world is increasingly and brazenly challenged by a number of few-holds-barred, charismatic strongmen from non-status-quo powers that eschew neither brinkmanship nor braggadocio; that divisive populist identity politics continue to poison the domestic political and societal wellsprings of our liberal democracies and our prosperity; that truth relativism is undermining any aspirations to develop more ‘rational’ and evidence-based international policies—all of these observations increasingly sow a deep sense of unease in many contemporary minds.

There are many expert-based overviews and analyses of ongoing trends in the international system, as well as attempts to extrapolate those trends into the future. This genre of ‘strategic foresight’ has developed into a regular cottage industry, for better and, we have argued, for worse.[5] In previous editions of this Strategic Monitor, however, we have over the years increasingly tried to move beyond the expert-picked to the more systematic, from policy-based evidence to evidence-based policy analysis. Providing a few (often deceptively) facile ‘narratives’ about these inevitably quite contradictory trends, or listing a certain number of major threats or risks—however well-selected and captivating—does not, in our opinion, a value-added, systematic monitor produce. The lists of risks or the narratives that result from such efforts almost universally tend to be far more revealing about the teams who generate them—their geographical, professional, ideological, cultural, theoretical, sometimes even generational and gender markers, as well as about the audience and/or customers for whom and the periods in which they write—than about the real ongoing dynamics in the international system they purport to reflect upon.

Global economic analyses and projections seem less bedeviled by these vagaries than broader geostrategic ones. Economists have for a long time developed and refined various metrics to capture some of the main dynamics of the global economy. Most yearly overviews of economic trends are heavily based on these datasets, certainly in the specialized literature, but even in more popular periodicals and newspapers. Most of us have become familiar with global economic indicators like world economic growth, global trade (including barriers to trade), global poverty, international M&A volumes, and other phrases of these sorts on which the world media frequently report. Until a few years ago, we had precious few analogous metrics to monitor the overall state of the international political system. We did (and do) have a number of structural datasets that allow us to measure a number of political and military actor attributes, such as democracy (Freedom House, Polity IV), rule of law and human rights (World Bank and Amnesty), military capabilities (IISS) or dyadic ones like conflicts and war. All of these structural datasets, however, have the drawback that they only become available at least one, and often two years after the year on which they report.[6] In a time like the present, where fundamental changes seem to be taking place at break-neck speed in the international system, this lack of near real-time monitoring data seems particularly unsatisfactory.

Fortunately, much of that is changing with the advent of various automated event datasets that are dramatically improving our ability to systematically monitor what is going on within and between countries at a much more granular level, as well as to intelligently aggregate and/or normalize these fine-grained events at the systems level. This allows us to start monitoring various international trends at different levels of analysis on a near real-time basis.

This report focuses on what previous Strategic Monitors have dubbed geo-dynamics,[7] as a more neutral and broader term than the more familiar—but also more value-laden—geopolitics. Geo-dynamics refers to ongoing dynamic patterns and trends in various key aspects of the international system. The four sections in this report attempt to make sense of these geo-dynamics from four different time perspectives. The first section looks back at what different ‘structural’ datasets tell us about the past ten years with respect to a number of key— i.e., geo-economic, geo-political, geo-societal, geo-judicial, and geo-identitarian—aspects of geo-dynamics. The second section moves from a ten-year, backwards-looking perspective to the more recent ‘present’: the past two years up to today. This is what we have called ‘nowcasting’[8] in previous monitors, referring to our attempt to at least get a more systematic and systemic monitoring ability of what is going on in the present beyond the anecdotal. In this section we first look at the systemic level, where we update our previously reported findings on global and regional levels of cooperation and conflict; we then take a small step down to take a closer look at what our datasets reveal about this world’s Great Powers and their assertiveness; and we conclude this nowcasting section by zooming in on the Netherlands and its changing role in these geo-dynamics. In the third section, we—for the first time ever—start extrapolating from these enormous datasets to project interstate dyadic risk in the future. As in the ‘nowcasting’ section, we present our overall findings at the systems level and at the great power (assertiveness) level, where we zoom in on a few countries (China, the Netherlands, Russia, and the USA). The fourth and final section takes a step back from the data and looks at these different time-horizons in order to ask the question where all of this leaves us—both in terms of method and in terms of substance.

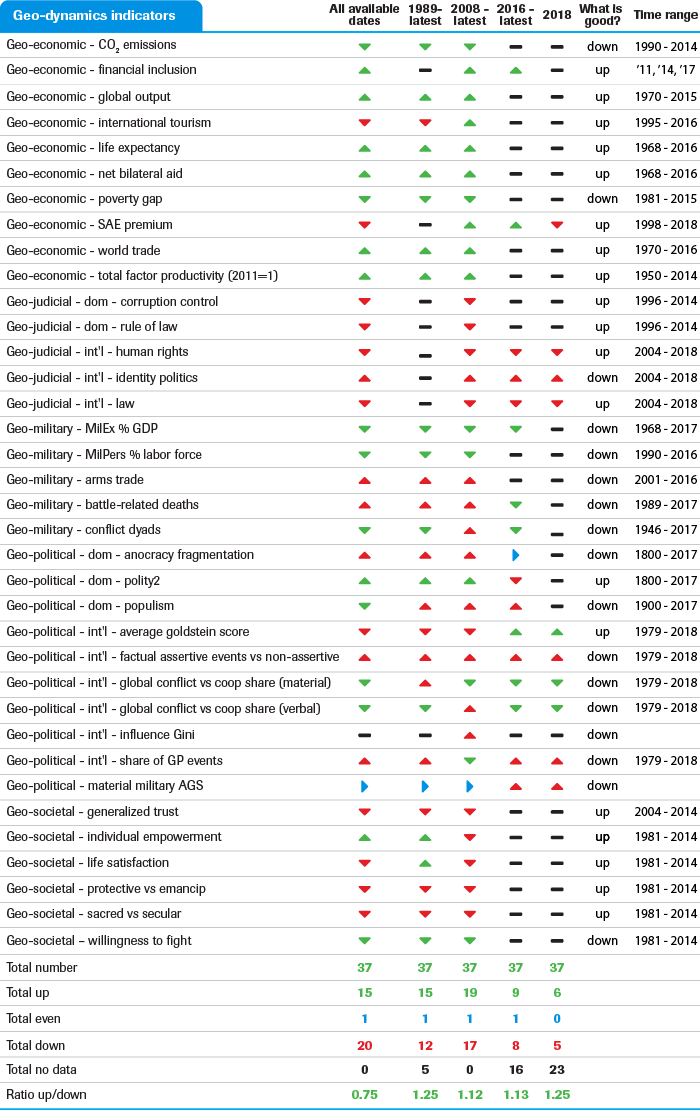

2. Looking Back: The State of Geo-dynamics in 37 Indicators

In this section, we set out to present the most important top-level data points about the current ‘state of geo-dynamics’ in 37 indicators that were selected to represent what we consider to be some of the key aspects of geo-dynamics. The actual availability of authoritative datasets varies widely across these different categories, but we still decided to pay attention this year to the geo-economic, geo-political, geo-societal, geo-judicial and geo-identitary aspects.

2.2 Geo-Economic

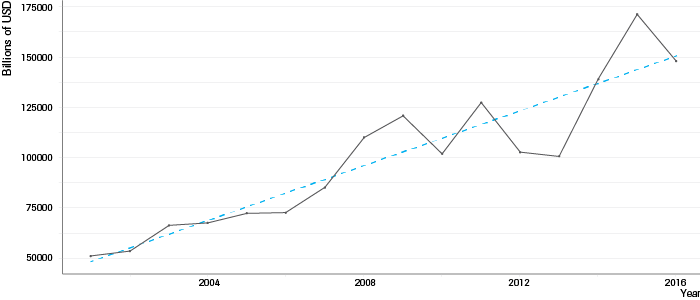

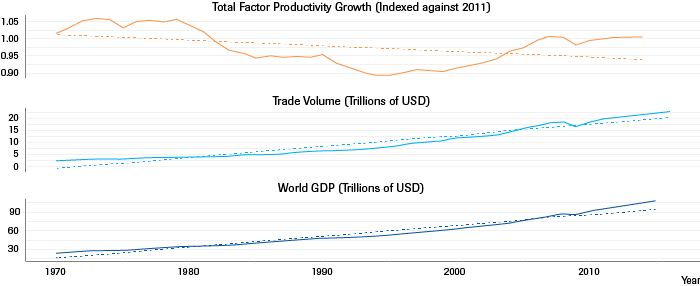

Source: World Bank, Angus Maddison & Groningen Growth and Debelopment Centre

A bird’s-eye glance at a number of key global economic indicators suggests that the world’s geo-dynamics in the economic realm have been—also historically—quite positive over the past decade.[9] Global economic output[10] has been growing again and in past years has been hovering around a relatively stable and healthy 3.8 percent per year, with growth slowing down, but not slow. The same is true for one of the underlying and increasingly important engines of this growth: technology innovation. One of the metrics that is widely used to measure this is Total Factor Productivity (TFP),[11] which indicates output per input of capital and (quality-adjusted) labor. TFP growth is also showing a downward, but still positive, trend. Recent research by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) also reveals that emerging market economies are benefiting from increasing use of foreign knowledge and technology over time, leading to a slightly more level playing field.[12]

In terms of international trade, the volume of world trade and services also exhibits a positive trend since 2012, in volume (as is visible on the chart), but also in composition and in nature, which may even be more important and positive. The composition of global trade[13] is shifting from often one-way streams of raw materials and finished goods between countries to more inclusive flows of intermediate inputs into sophisticated and dynamic international value chains. And global trade’s nature is transforming from goods to data and services.[14] Thus still forges ahead—albeit it in a noticeably different way—the powerful march of globalization that stretches back millennia[15] but that has particularly gripped and transformed the world in the first two decades after the end of the Cold War. This continued globalization trend endures, to a large extent, even in economic-institutional terms, as nations continue to conclude new trade agreements. Even after the financial-economic crisis in 2008, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) was signed (initially with the US at the helm, now continuing without), much of Europe created a banking union and capital markets union after the Eurozone crisis, China launched a multilateral development bank as well its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and Canada, Mexico, and the US even signed a new free trade agreement in 2018. If we look below the level of the nation-state, we also see that regions, cities, and especially private companies and (groups of) individuals are forging myriad new forms of connections between themselves.

Many other economic indicators confirm this fundamental positive trend, many of them boosted by the last decade of slow but fairly steady economic recovery.

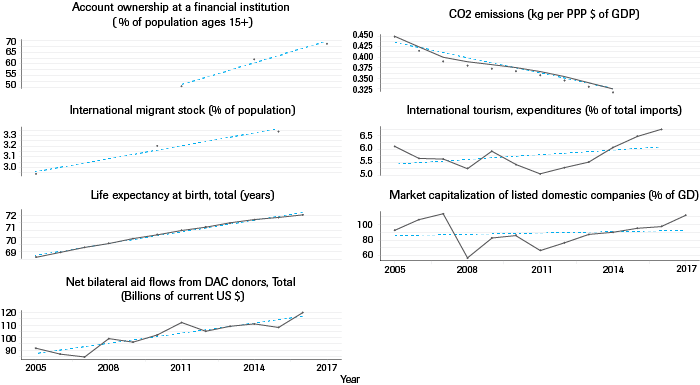

More and more people across the world now have direct access to and also use banks (often through mobile phones),[16] international tourism has picked up again, aid flows are increasing, global market capitalization is up, global life expectancy at birth is still edging up, CO2 emissions continue to come down (albeit not nearly at the rate that would be required to meet the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) recommendations),[17] and the list of changes for the better goes on.[18]

These positive developments over the past decade, while empirically accurate (and maybe in some senses even understated)[19] may, however, still paint an overly optimistic picture. The baseline for this decade coincides with the biggest downturn the world has seen since the interbellum last century, and therefore upward trends following such a low starting point should come as no great surprise. Many also argue that the year 2016 may still go down in history as a real turning point, with Brexit and Trump’s ‘populist sovereignism’[20] turn as potentially the first opening shots in a new and conceivably more confrontational and dangerous geo-economic dynamic even within the rich West that has been so dominant since the industrial age.[21] Over the past two years, much protectionist rhetoric has been bandied about by various governments, and the first real salvoes have been fired by the US in a number of potential trade wars, leading to instant retaliation by their targets. To this day, however, it remains unclear whether these initial salvoes will prove to have been mere shots across the bow by a few Anglo-Saxon buccaneers testing the waters, the opening shots of a genuinely new era in great power (or regional bloc) competition or even conflict accompanied by ‘beggar-thy-neighbor’ practices; or the parting shots of a massive financial-economic crisis that may prove one of the interludes (maybe even one of the milder ones in comparison with the two previous ones—the two world wars in the past century) in a century- (or even millennia-)long trend towards more international economic openness, connectedness, efficiency, and (absolute) welfare gains.

There are also other reasons why a linear extrapolation from the positive economic trends of the past decade may be ill-advised. One of the most recent versions of the IMF’s World Economic Outlook[22] mostly focused on the longer-term damages that the 2008 financial meltdown might have caused. The Outlook emphasizes that the downside risks to global growth have risen in the past six months, whereas the potential for upside surprises has receded against what it calls a “context of elevated policy uncertainty.”[23] Escalating trade tensions and the potential shift away from a multilateral, rules-based trading system are seen as key threats to the global outlook. The added likelihood of a continued (and possibly even sharp) tightening of currently still-easy global financial conditions is also expected to expose a number of vulnerabilities that have accumulated over the years. These include the potential continued build-up of financial vulnerabilities, the implementation of unsustainable macro-economic policies amid a subdued growth outlook, rising inequality, and declining trust in mainstream economic policies.

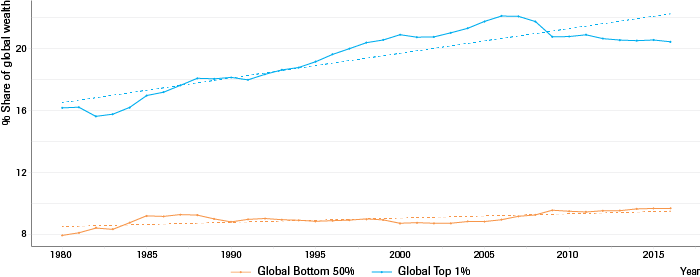

Another one of the primary areas of concern remains the issue of geo-equity. This term refers to the notion of global economic fairness between, across, but also within states: even as the pie is growing, does everybody get to benefit equally—or at all? The importance of this issue is also amplified by the growing recognition (partially driven by the populist backlash) that equity—or at least equal opportunities for upward mobility—is not just morally desirable, but even economically and politically efficient. Our datasets on these geo-equity issues, while far from perfect, have improved dramatically over the past few years, especially at the individual income level.[24]

Source: World Inequality Lab

At the individual level, these new datasets[25] do indeed bear out the widely-repeated findings that the discrepancy between the top 1 percent and the bottom 50 percent of global incomes has widened significantly in the more traditional globalization spurt that characterized the three decades prior to the financial-economic crisis. In this period, the share of the top 1 percent of incomes exploded from about 15 to almost 25 percent of global incomes. But these same data also show that the 2008 crisis hit those same one-percenters disproportionally heavily, bringing their share back down to 20 percent, whereas the share of the bottom half continued its slow increase (see - trend is upward since 2006). Although data are less readily available on between-country convergence, US economist Richard Baldwin talked in 2016 about a ‘Great Convergence’[26] in which developed country firms started unbundling production stages and moving labor-intensive components of production to low-wage countries, allowing developing countries to industrialize and gradually crawl up the global value chain without building their own entire supply chains. To illustrate this convergence: emerging markets currently account for 59 percent of the world’s output (measured by purchasing power), up from 43 percent just two decades ago.[27] As with global trade, recent mercantilist rhetoric (and initiatives) may still put a dent in, or even reverse, this great convergence story. In many cases—first and foremost in that of the United States—it remains unclear whether recent protectionist initiatives are bargaining ploys to achieve a truly more level global playing-field, as President Trump has repeatedly claimed, or whether they instead prove to be the modern-day equivalent of the Corn Laws in the UK in 1815, which revealed the shortsightedness of such mercantilist instincts and whose repeal in 1846 was one of the major breakthroughs for the unprecedented globalization spurt that started in the second half of the 19th century.[28]

2.2 Geo-Political

The modern and once again more salonfähig version[29] of ‘geo-politics’ tends to focus on the spatial dynamics between the world’s (especially great) state powers. It tries to make sense of how these (state) power dynamics are changing and shifting geographically. Especially en vogue in this community are narratives about how power is shifting from ‘the West’ to ‘the East’; or how the more skilled, determined, and even ruthless application of ‘raw’ power by certain modern-day geo-political entities may affect other less skilled or less determined ones. We have wondered before what the most useful scope of ‘geo-political’ analysis should be, and whether focusing so doggedly on (especially major) state actors and on certain instruments of so-called ‘hard’ power does not do a disservice to the very term ‘geo-politics’ and more broadly to the spatial analysis of power politics it purports to provide. What is happening to power may very well go beyond the sheer geographical shifts in the center of gravity of power in the world or the alleged re-discovery of national interest and ‘real’ power instruments. Instead, the very nature of international (and transnational) power and agency, their attributes, sources, structure, distribution channels across various (also non-state) actors—all of these fundamental aspects of power may be changing before our very eyes in new and as of yet poorly understood ways.[30] We are also witnessing the changing nature, size, composition, and interaction of non-state political power(s). Prudent strategic decision-makers today ignore the dangers and opportunities lurking in the more traditional, linearly state-centered ebbs and flows of political geo-dynamics at their own peril. But they would be at least equally ill-advised to ignore the dangers and opportunities that reside in the wider (sometimes also non-linear and emergent) manifestations of power at different levels and in different domains.

As with many other aspects of geo-dynamics, our ability to systematically monitor these various spatial dynamics of power is limited. In this section, we will focus on a few of systematic longitudinal datasets that provide insights about the international and the national dimensions of political power and how it is globally distributed.

2.2.1 International

In 2018, the Atlantic Council of the United States, the University of Denver's Pardee Center for International Futures, and HCSS analyzed what a new dataset—the Pardee Center’s Bilateral Foreign Influence dataset—tells us about power and influence in the world.[31] That dataset does not merely look at (monadic) national attributes of power, but at the (dyadic) links of (diplomatic, economic, and military) influence and power. The study also revealed some less well-known insights that we will briefly summarize here, while referring the interested reader to the actual study.

Global influence is concentrated in the hands of the few. Only ten countries possess about half of the world’s influence.

Similar to trends in the global distribution of power, global influence has been dispersing. A growing number of states wield greater amounts of influence over larger geographical distances.

The US still retains a global lead in terms of its share of global influence capacity, but its share has been decreasing and is considerably smaller than its share of the world’s coercive capabilities.

China’s upward trajectory has been impressive. It has vastly expanded its influence, not only in its own region but also outside of it, including in NATO member states and in Africa at large, where it has surpassed the US.

Russia’s trajectory has been similarly dramatic, but in the opposite direction: it has lost considerable amounts of influence, including in countries in the former Soviet space.

European states, including some small ones such as the Netherlands, punch significantly above their weight in comparison to the size of their economies.

Great powers continue to vie over spheres of influence for a variety of military–strategic, economic, and ideological reasons. Pivot states are located in the Middle East, Central Asia, Southeast Asia, Latin America, and West Africa.[32]

The past two decades saw the emergence of new networks of influence and the reconfiguration of others around dominant hubs, including in the Middle East and China.

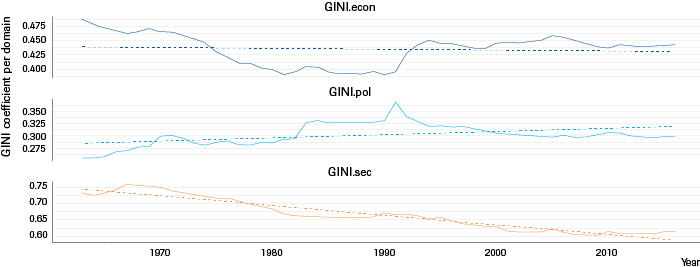

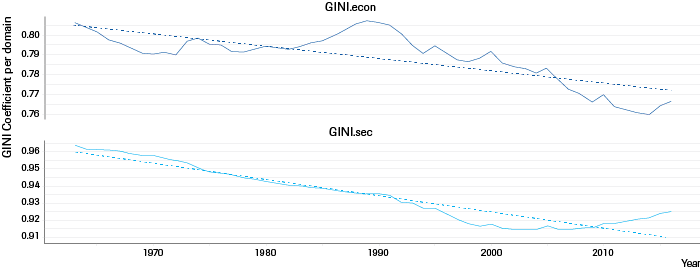

To summarize the longer-term, systemic-level trends in international influence, HCSS computed the Gini coefficient[33] for the amount of influence that countries wielded over other countries from 1963 to 2016. A first observation is that the Gini coefficient for international influence is quite high—higher, in fact, than the traditional Gini coefficient that measures inequality within countries.[34] Secondly, we also see that international influence has become slightly more balanced across countries over the past decade. A closer look at the difference between economic and military dependence (one of the two indicators that make up the overall influence score) shows that security influence is significantly less equally distributed across the world than economic influence, and this has become more unequal over the past decade. Inequality in economic dependence, on the other hand, has been declining noticeably since about 1990, but has been growing again in the past few years.

Source: HCSS Calculation, based on Pardee Global Influence

Source: HCSS Calculation, based on Pardee Global Influence

2.2.2 National

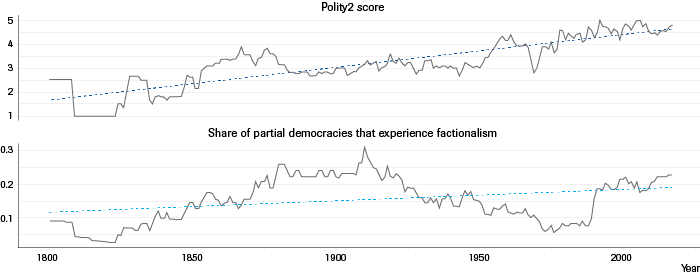

We are also witnessing some evolutionary rather than revolutionary changes in our national polities—changes that also matter (indirectly and directly) to international relations. There is a large body of literature on how countries’ political regimes matter to various domestic and international economic, social, military and other output variables.[35] One of the most widely used metrics of regime types is the Polity IV dataset[36] that codes democratic and autocratic "patterns of authority" and regime changes in all independent countries since 1800. The following vizzes (Figure 6) show changes in two important variables from this dataset: the Polity2 score, which ranks countries on an interval-level scale from +10 (strongly democratic) to -10 (strongly autocratic); and the share of partially democratic countries with high amounts of political factionalism, meaning many “identity cleavages and factions that challenge the coherence and cohesion of authority patterns within the shared, central polity.”[37] The reason we selected these two variables is that they have been shown to be highly correlated with political violence.[38] For Polity2, we show the yearly average of all countries available in the dataset; for factionalism, we display the share of partial democracies that experience it against all partial democracies.

The data shows that the average Polity2 score increased dramatically since 1800 until the 1920s, when the rise of populism and even fascism threatened the legitimacy of many established democracies. It took a world war to overcome that threat, after which decolonization and the emergence of many newly independent states with lower polity scores led to a second decline in the world’s level of democracy. The end of the Cold War saw yet another democratization wave that rose to far higher levels than in the pre-World War II era. We see that since 2008 (the global financial meltdown) that upward trend has slowed down somewhat, but not to the extent some pundits[39] have proclaimed.[40]

The data on factionalism, however, show that the share of partial democracies—countries with Polity2 scores from (including) +1 to +6[41]—that experience factionalism has been increasing steadily since the late 1970s and reaches almost 23 percent in 2016. Based on what recent scholarship has revealed about the link between these political characteristics and political instability, this is certainly a cause for concern.

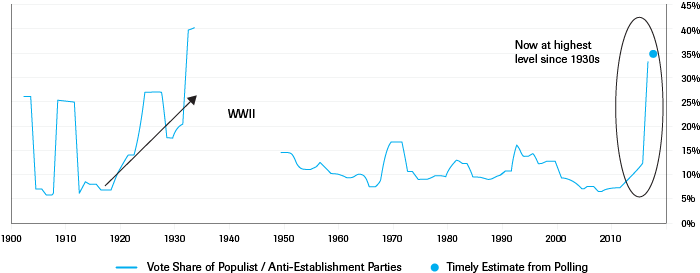

The final political data point that deserves to be taken into account is the particularly virulent bout of populism that many democratic polities are clearly going through.[42] As pointed out in research by the hedge fund Bridgewater,[43] populism is currently at its highest level since the late 1930s (even though they hastened to add that the ideology of the populists today is much less extreme compared to the 1930s).

2.3 Geo-Military

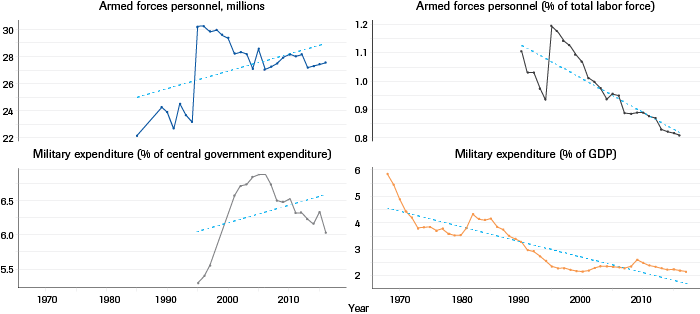

There are a number of data points that can be used to get a better sense of where military geo-dynamics seem to be heading. Figure 8 shows two publicly available and (therefore)[44] widely used indicators—the number of military personnel in the entire world, as well as global military expenditures.[45] It shows these in different ways, however, to illustrate how easily they can be abused.

If we look at two line graphs on the left—representing the overall absolute numbers of soldiers in the world, and the part that global military expenditures represent in overall government expenditures—we see a clear rising trend over the years for which data are available (but also a decline in more recent years since 2006). Both of these signals are meaningful. The more soldiers there are in the world, one could argue, the higher the risk that they might clash with each other and the higher also the absolute numbers of military casualties that would result from such clashes. By the same token, the demonstrable fact that the world’s governments have proved willing to spend a growing part of their tax revenues on defense, in a era where non-military budget items are becoming increasingly politically contested (even in more authoritarian countries), is quite telling. At the same time, however, if we put these figures in a broader context (as we do in the two line graphs on the right), we can paint an entirely different—and far rosier—picture. With respect to military personnel numbers, we see that rising absolute numbers actually represent a starkly declining relative proportion of the active labor force.[46] The same applies to military expenditures relative to GDP instead of to government expenditures. Here we see that the world’s economies have been growing far more rapidly than government expenditures, and so that the proportion of the world’s overall ‘wealth’ that states have allocated to the military has actually declined.[47] This last line graph also nicely illustrates the so-called ‘peace dividend’ after the end of the Cold War, which seemed to start reversing itself in 2008-09, but which has declined again since then. We cannot fail to point out that the global average on this indicator (2.17 percent of GDP) is still significantly higher than the current European (including Dutch) percentage or than the NATO 2 percent ‘target’. We therefore submit that it is important to always report on both sides of these trends—both the absolute and the relative one.

For the next and at least as important (and probably also ‘leading’)[48] geo-military indicator, the global arms trade,[49] we unfortunately only have absolute figures. These SIPRI data still clearly show, however, that despite noticeable fluctuations every few years the global arms trade is booming—a trend we suspect would still be visible even if we were to normalize the data for expanding global wealth.

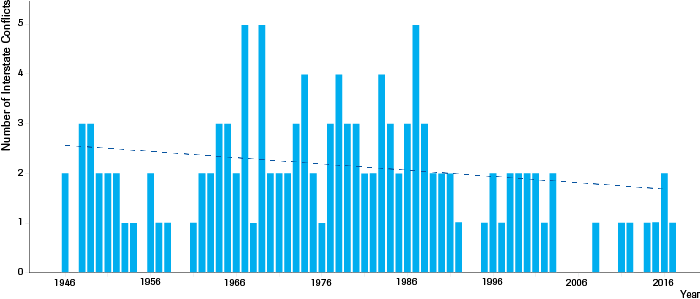

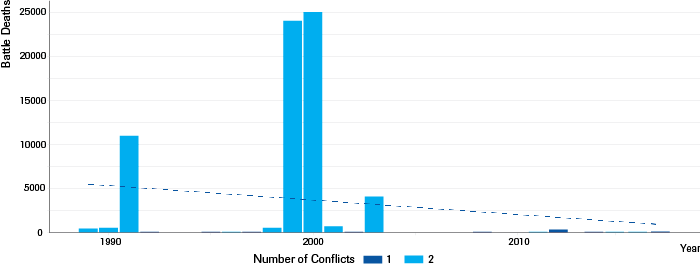

What do we find when we take a closer look at actual international military clashes? Figure 10 visualizes the yearly number of dyadic—between two states—armed conflicts (as measured by the UCDP Armed Conflict Dataset).[50] It has discernibly decreased over the last forty years; however, with the past two decades showing further decline.

2.4 Geo-Societal

One of the important messages the (at least) past few years have clearly driven home is that geo-dynamics do not merely reflect the global economic, political, and military waves we see fluctuate at the surface of the international system. There are also deeper undercurrents at work here that are undoubtedly connected to these aforementioned waves but that also have logics and dynamics of their own. The rise of what are sometimes called post-materialist values[51] in different, more developed parts of the world is clearly a reflection of the higher living standards that better governance, more informed economic policy, and the absence of conflict brought about there. But they in turn also start affecting those drivers, as they lead to different consumption, voting, and even security (and increasingly also privacy) priorities. The reverse can also be said of the countervailing undercurrents of resentment and revanchism, both within our own societies and in societies further away.

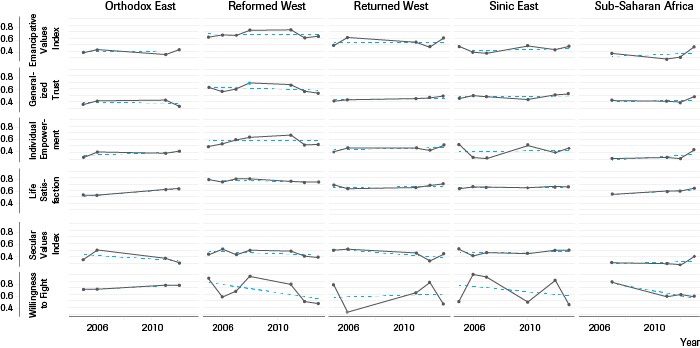

What do we know about these ‘deeper’, also values-based societal or even cultural geo-dynamics across the world? Is the world becoming on average more or less like the (mostly) post-modern Western liberal democracies? And how would we know? The single largest and most widely-used global dataset on these questions is the World Values Survey,[52] a massive undertaking in which a worldwide network of social scientists has conducted, since 1981, representative national surveys in almost a hundred countries in order to explore people’s values and beliefs, how they change over time, and what social and political impact they have.

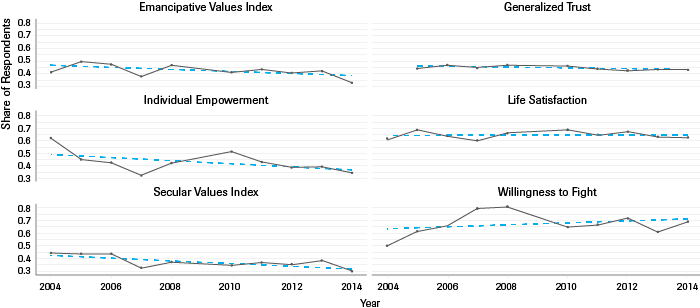

In this section, we report on a number of the key aggregate variables, for which we, just like in the previous section, computed the mathematical mean for all countries included in the survey. The variables we selected for inclusion are the:

Emancipative Values Index, “Protective-vs.-Emancipative Values,” a twelve-item index measuring a national culture’s emphasis on universal freedoms in the domains of 1) reproductive choice (acceptance of divorce, abortion, and homosexuality); 2) gender equality (support for women’s equal access to education, jobs, and power); 3) people’s voice (priorities for freedom of speech and people’s say in national, local, and job-related affairs); and 4) personal autonomy (independence, imagination, and non-obedience as desired qualities in children). The scale ranges from a theoretical minimum of 0 when the least emancipative position is taken on all twelve items, to a maximum of 1.0 when the most emancipative position is taken on all items. Intermediate positions are given in fractions of 1.0;

Secular Values Index, “Sacred-vs.-Secular Values,” a twelve-item index measuring a national culture’s secular distance to “sacred” sources of authority, including: 1) religious authority (faith, commitment, practice); 2) patrimonial authority (the nation, the state, the parents); 3) order institutions (army, police, courts); and 4) normative authority (anti-bribery, anti-cheating, and anti-evasion norms). The scale ranges from a theoretical minimum of 0 when the least secular position is taken on all twelve items, to a maximum of 1.0 when the most secular position is taken on all items. Intermediate positions are given in fractions of 1.0;

Individual Empowerment, version 2. This is another multi-item index measuring the extent to which the people in a society are mentally and habitually empowered to make their own choices and to exhibit them in their actions. The index covers the domains of 1) motivational empowerment (emancipative values); 2) intellectual empowerment (formal education); and 3) behavioral empowerment (social movement activity). Scaling is based on a multi-point index with original scores on each of the multiple items rescaled from minimum 0 to maximum 1, with proper fractions for intermediate positions, and then averaged over all the measures;

Generalized Trust is an index that measures to what extent trust in others is general, assigning increasing weights to trust’s generality from close to unspecified to remote others as In-Group (1), Out-Group (2), and Unspecified (3). Here, too, scaling is based on a multi-point index ranging from 0 when there is no generalized trust to 1.0 when the opposite is the case, with proper fractions for intermediate positions. Country-level scores are the average of each national sample;

Life Satisfaction is a ten-point item indicating to what extent people are satisfied with their lives as a whole. This variable is rescaled from minimum 0 for the least to maximum 1.0 for the most satisfaction, with fractions for intermediate positions. Country-level scores are the average of each national sample;

Willingness to Fight refers to a dummy item that indicates whether or not people are willing to fight for their country in the case of war.

Of all of the sub-categories we report on in this more backwards-looking section of our geo-dynamics indicators, this one undoubtedly paints the gloomiest picture of the whole period. We find for every single one of these indicators that while most Western—or at least European—liberal democracies would presumably like to see an increase in the world (life satisfaction, trust, individual empowerment, emancipation, and secularism), the opposite is actually occurring. However, some positive trends can be identified as well. For instance, people’s willingness to fight (usually an alarming trend) has actually decreased in recent years. We want to emphasize, however, that the crude country-wide averages we are showing here have not (yet) been weighed by their population.

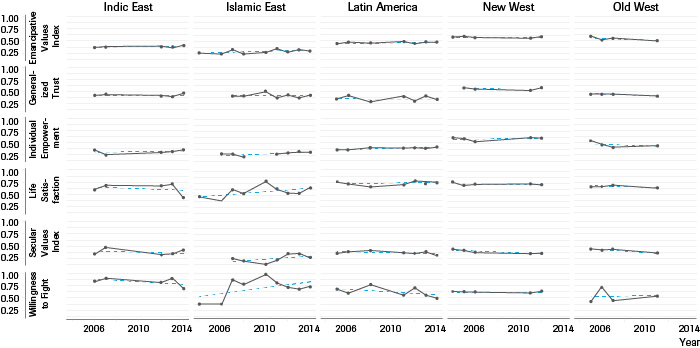

A closer-up look at the underlying regional differences indicate, however, that there are still glimmers of hope in a number of the ‘cultural zones’ that were developed in the margins of the World Values Survey.[53]

We note that in quite a few up-and-coming zones—the Sinic East, Latin America, the Returned West,[54] the Orthodox East, and even the Islamic East—many of the trend lines are indeed heading in the direction that European liberal democracies currently desire. Then again, some apparent trends, like the average willingness to fight in the Returned West and Islamic East, reflect and raise major concerns.

2.5 Geo-Judicial

The final two categories of this backwards-looking geo-dynamics section are the ones where we arguably have the weakest datasets, despite the fact that they are widely acknowledged to have been and to continue to be of paramount importance to the past, present, and future stability of the international system. The importance of a well-organized and effective legal system (the famous ‘law and order’-nexus) as a foundational pillar of political stability is widely acknowledged. That is certainly the case at the domestic level.[55] But also internationally, the few remaining ‘ungoverned’ black holes of the world where law and order have collapsed—or where the foundations were never even laid—serve as constant reminders of how deep homo sapiens can sink in the absence of some form of legal-institutional structure. Longue durée historians[56] now tend to concur that ‘law’, together with a number of other attendant ‘social technologies’[57] emerged in the lucky latitudes at the time homo sapiens started settling down in ever larger and more complex settlements that required more political ‘management’ than hunter-gatherer societies could muster. Over the subsequent centuries, these social technologies matured in different ways in various parts of the world, but by the modern age, the idea (and the reality) of the ‘Rechtsstaat’ became a widely accepted form of ‘best practice’. One that many polities, of various stripes, continue to struggle with to this very day.

Given the importance that the Netherlands puts on the further strengthening of international law[58] and the fact that “to protect and promote the international rule of law” is the second main task of the Dutch armed forces (anchored in Article 97 of the Dutch constitution, as revised in 2000),[59] we decided to take a closer look at this aspect of geo-dynamics.

2.5.1 National

The extent to which the rule of law is upheld in different countries across the world is captured in one of the World Bank datasets on World Governance Indicators,[60] which contains at least two variables that seem pertinent to this issue:

“Control of Corruption” captures perceptions of the extent to which public power is exercized for private gain, including both petty and grand forms of corruption, as well as "capture" of the state by elites and private interests. Our data show the average ‘estimates’ for all countries’ scores on this aggregate indicator, in units of a standard normal distribution, i.e., ranging from approximately -2.5 to 2.5;

“Rule of Law” captures perceptions of the extent to which agents have confidence in and abide by the rules of society, and in particular the quality of contract enforcement, property rights, the police, and the courts, as well as the likelihood of crime and violence. Our data once again show the average ‘estimate’ for all countries’ scores on this aggregate indicator, in units of a standard normal distribution, i.e., ranging from approximately -2.5 to 2.5.

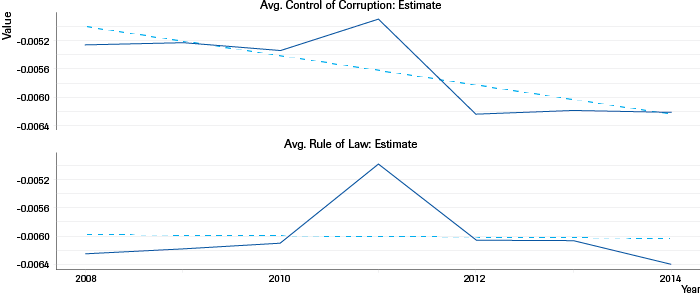

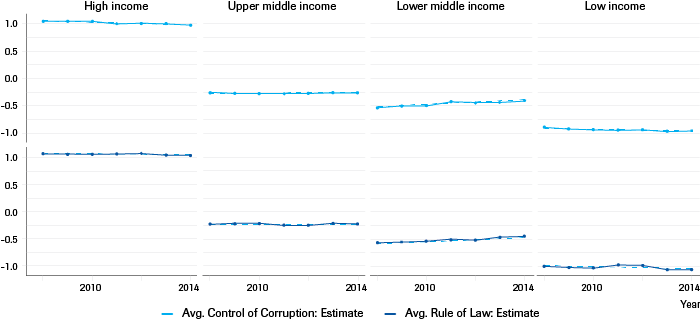

As Figure 13 shows, the data for these two variables since 2008 show a slightly deteriorating trend line over the entire period—especially in terms of control of corruption, with both indicators hovering just below the ‘neutral’ 0-level.

Source: World Bank, World Governance Indicators

A breakdown of these same data by country income level (based on the 2018 World Bank classification) reveals that only the lower-middle income group actually shows a fairly steady improvement, whereas all other groups experience declines. This suggests that the international community has not yet succeeded in finding effective ways of improving the often endemic corruption levels in these countries.

Source: World Bank, World Governance Indicators

2.5.2 International

Although these data show that much work remains to be done at the national level, at least most countries have and sustain some form of national legal order that can adjudicate various disputes in a non-violent way. At the international level, however, progress towards ‘global’ law and order has been far slower and more checkered. States are still able to violate some of the most hallowed principles of international law with relative (though no longer absolute) legal impunity—as Russia’s 2014 annexation of Ukraine’s Crimea region most vividly demonstrated.[61] Our ability to monitor the extent to which various disputes have been met with a legal solution in international courts remains surprisingly limited, and this is definitely an area into which HCSS intends to put more effort and creativity.

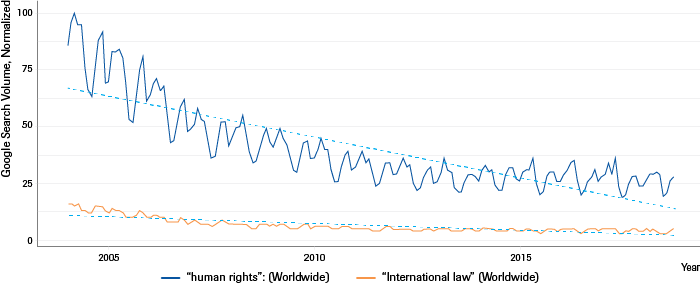

Figure 15 from Google Trends[62] tries to capture at least one aspect of this international judicial aspect of geo-dynamics: the extent to which the global (English-speaking) general public expresses an interest in the issues of ‘human rights’ and ‘international law’ (as witnessed by their search history) and how that revealed interest changes over time (in relative figures, compared to the ‘human rights’ query peak popularity).[63] These data show declining global public interest in both topics, although this seems to have bottomed out somewhat in the past ten years.

Source: Google Trends

Also here, however, we would submit that there is a glimmer of hope[64]—even if we have not (yet) been able to find or develop truly reliable quantitative indicators for it.

2.6 Geo-Identity

As we argued, documented, and analyzed in our 2017 study on The Rise of Populist Sovereignism,[65] the shift from the certainties of the ‘solid’ world to the increasingly and constantly changing ‘liquid’[66] nature of many aspects of our everyday lives, relationships, and societies has disoriented the identity of many citizens in ways that populist political entrepreneurs have been able to leverage in order to challenge existing political equilibria. Much of this backlash is undoubtedly related to more material developments in the economy, technology, etc. However, much of it is likely also of a more immaterial, ‘identitarian’ nature.[67]

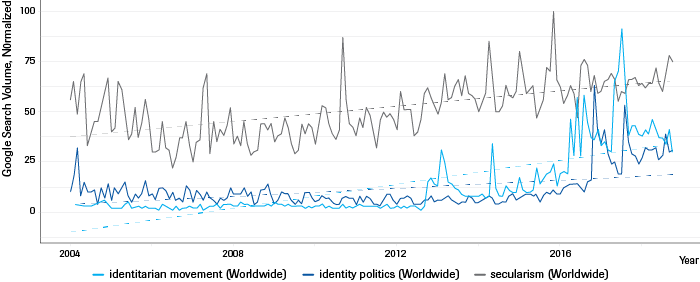

Source: Google Trends

These Google Trends data (Figure 16) show that (at least) English-speaking internet users increasingly were curious enough about issues like ‘identity politics’, ‘identitarian movement’, and ‘secularism’[68] to look these up on Alphabet’s Google Search.[69] This trend is especially poignant for the two identity-based search terms, which have seen significant spikes over the past two years.

In our 2017 Populist Sovereignism study,[70] we placed much emphasis on the socio-economic and political-institutional drivers of Populist Sovereignism and on the (difficult but at least fairly well-understood and relatively tractable) policy options in that area. A year later, we find ourselves slightly more hesitant on both that analysis and on the policy inferences we drew from it. The—so far—(to many surprisingly) steadfast loyalty of supporters of US President Trump, of Brexiteers in the UK, of various right-wing groupings in Europe, but also of many Chinese, Indian, Russian, Turkish and other PopSovists to their causes, in spite of often increasing evidence that these might contradict their personal or collective economic prospects, may suggest that identity formation and manipulation (and therefore also identity defense and resilience) may play a more important driving role in international stability than most of studies (and models) of these issues suggest. We therefore submit that this too is an area for which future strategic monitors will have to develop better sensors (and effectors).

3. Looking at the Present:

Nowcasting Geo-dynamics

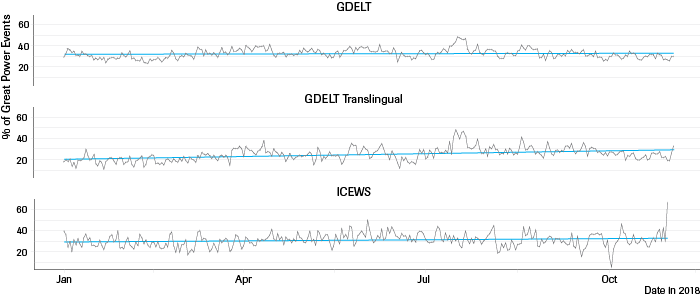

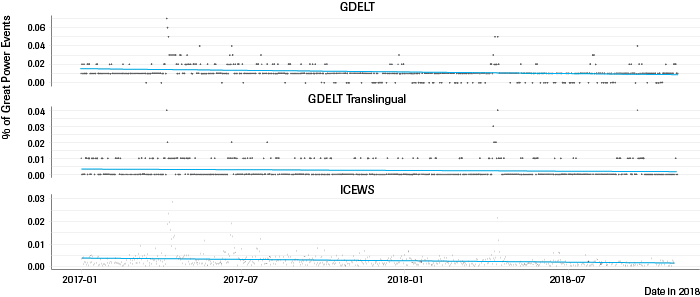

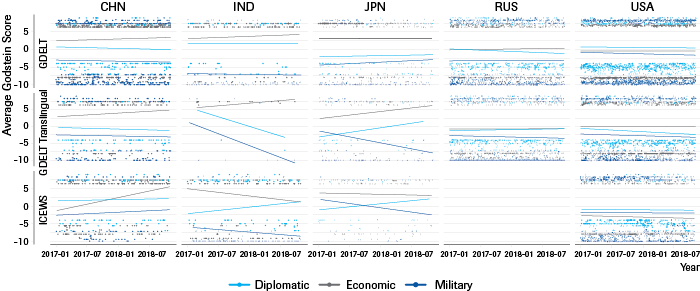

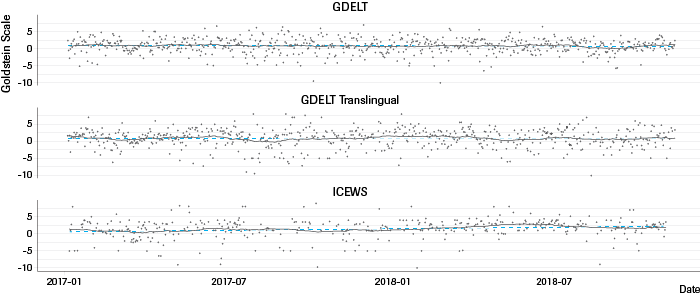

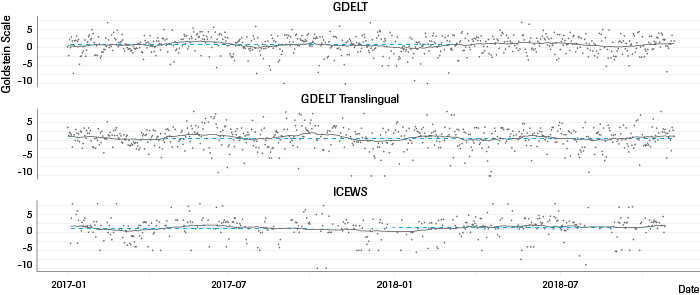

In this section we take a closer look at the more recent past (and especially at the data for 2018) that the more structural datasets do not have data for (yet). It is based on three event datasets that—usefully—all use the same event coding scheme (CAMEO),[71] making it easy for us to compare and analyze their findings: GDELT2[72] (both English and Translingual), ICEWS,[73] and the new ‘real-time’[74] datasets. Although they all use the same coding scheme, they still differ quite a bit in many other important aspects. We leverage these differences to filter out only those patterns or trends that can be discerned in the majority of available datasets.[75] More methodological details on event datasets and our use of them can be found in an upcoming annex “Events Datasets and Strategic Monitoring.”

3.1 Global Cooperation and Conflict

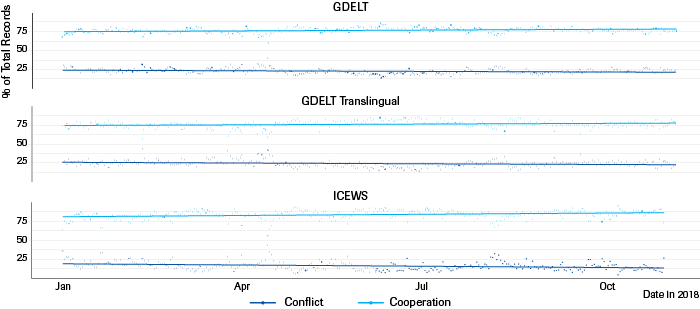

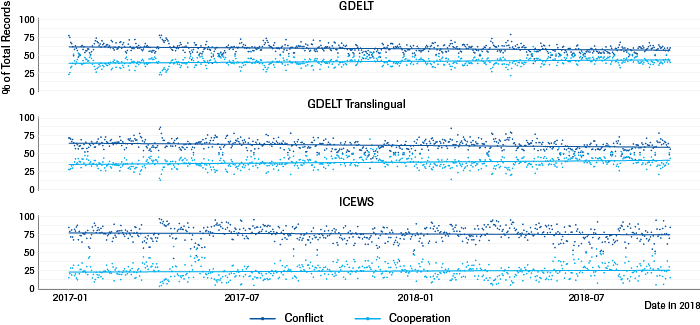

In stark contrast to the widely-felt global angst that has gripped our public debates and even private discussions about the international system, both of the metrics[76] that we have used to monitor global conflict and cooperation show a positive trend in every single one of our automated event datasets. Throughout 2018 the interstate trend at the system level—meaning all recorded interstate events—has been towards (slightly) more cooperation and less conflict, both in the material and the verbal categories (even though conflict remains dominant in material events).

3.1.1 Overall

Source: HCSS calculations based on GDELT (English and Translingual) and ICEWS

3.1.2 Material

Source: HCSS calculations based on GDELT (English and Translingual) and ICEWS

3.1.3 Verbal

Source: HCSS calculations based on GDELT (English and Translingual) and ICEWS

The slight decline is even the case for purely military events. If confirmed by the human-coded UCDP “Battle-Related Deaths,”[77] this finding would provide further evidence for the decline in the past few years—contrary to widespread popular opinion—in the number of global interstate conflict fatalities across the world. Some may see this as the continuation of a long-term fractal decline of (also interstate) violence,[78] others may interpret it as a new (or rather, ‘modern’) form of ‘hegemonic deterrence’ that the US president may have (accidentally?) stumbled onto and that may or may not prove sustainable; still others may just call it a fluke, a stage transition, or ‘silence before the storm’. Whatever narrative one prefers, it remains striking that this appears to be such a robust observation across the datasets.

Source: UCDP, Battle-Related Deaths Data

3.2 Great Power Assertiveness

Given the Great Powers’ continued disproportional salience in the international system, we have paid close attention to developments in their assertive rhetoric and behavior in various contributions to the Strategic Monitor since 2013.[79]

Our data from the different automated event datasets for the year 2018 show that Great Powers seem to be regaining control of international events again. Their relative share of all interstate events, which had declined quite notably in 2017, picked up again in 2018 and reached new heights unseen since the end of the Cold War.

Source: HCSS calculations based on GDELT (English and Translingual) and ICEWS

We reported in 2017 on how many Great Powers (including China and Russia) seemed to be ‘lying relatively low’ in terms of their international assertiveness. We conjectured that this might be a response to the possible deterrent effect of a more prickly and unpredictable global hegemon under President Trump. Our data for this year see the Great Powers as a group behaving far more assertively across the board in 2018, especially in the beginning of the year and in the summer. This is also the case for just material events, although the gap is smaller there. The only exception here is in the important category of military material assertiveness. Great Powers as a group still seem to be 'lying low' in terms of military material assertiveness in 2018—other than a (mostly Syria-related) peak between March and May. But the trend over 2017 and 2018 is downward.

Source: HCSS calculations based on GDELT (English and Translingual) and ICEWS

An analysis of the individual Great Powers reveals that, in line with our findings for the preceding years, the US remains by far the single most negatively assertive great power in factual military events over 2017 and 2018, although Russia on various days also jumps out of the group (again primarily Syria-related).

Source: HCSS calculations based on GDELT (English and Translingual) and ICEWS

When we compare these findings with previous years, however, we do note that the US exhibited more negative (factual) military assertiveness in last two years of the Obama administration than in the first (nearly) two years of the Trump administration.

The Chinese story remains complicated as well. Overall we see increasing negative assertiveness from China over the past five years, but the figures for 2018 are lower than those for 2017 and we observe a slow yet evident decrease in negative diplomatic and (despite a number of striking peaks) also military assertiveness over this period.

3.3 The Netherlands in Geo-dynamics: Leaving Paradise?

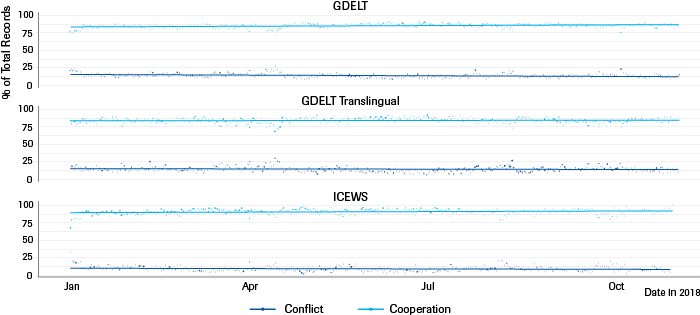

3.3.1 World -> NLD

Source: HCSS calculations based on GDELT (English and Translingual) and ICEWS

In previous editions of the Strategic Monitor, we reported that the Netherlands still found itself comparatively speaking in an extremely favorable position in terms of how the world in general—and the Great Powers in specific—behaved towards it. Our findings for 2018 are slightly more checkered.

The metric we use to gauge the tone of the relationship between two countries (the average Goldstein score) shows that the world as a whole had a slightly more positive attitude towards the Netherlands in 2018 than in 2017,[80] in words and in deeds. A closer look underneath this still comforting high-level observation at the different functional categories (diplomatic, informational, security, military, economic, and legal—‘DISMEL’ for short) in which we bin our events, however, reveals a more inconsistent picture, with different datasets coming to different conclusions for the various categories. The second metric we use to track broader geo-dynamic shifts in these different categories, namely the proportion of (binary) conflictual versus cooperative events, also does not indicate any noticeable shifts.

3.3.2 NLD -> World

Source: HCSS calculations based on GDELT (English and Translingual) and ICEWS

In two out of the three datasets for which we have data for 2017 and 2018, we see the Netherlands behaving factually slightly more negatively towards the rest of the world in 2018 as compared to 2017 (but still in overall ‘positive’ (+0) territory). The biggest declines are seen in the diplomatic and economic realms, whereas in the military one the Netherlands proved less conflictual in 2018 (e.g., due to fewer Syria-related events).

3.3.3 The Netherlands in the Geo-dynamic Maelstrom

Our ‘two-way’ findings this year do not imply ‘Paradise Lost’ quite yet. Our main high-level findings on global levels of conflict and cooperation suggest that events in 2018 did not only not deteriorate (as global headlines keep clamoring) but even (slightly) improved.

The Netherlands continues to benefit from relatively sound and stable ‘fundamentals’ at home, an internationally enviably stable neighborhood, and comparatively still high levels of international goodwill. But the solid foundation that these three elements have cemented are starting to show worrying cracks, as our findings also suggest. Brexit, the building Populist Sovereignism crest throughout and other fissures within Europe (including the Netherlands itself), growing Transatlantic drift, the continued pressures along the European border—all of these elements are increasingly jeopardizing the political steadfastness, economic prosperity, security stability, societal ‘sanity’, and maybe even the high quality of life and wellbeing that have characterized this country and its immediate neighborhood for the past half century.

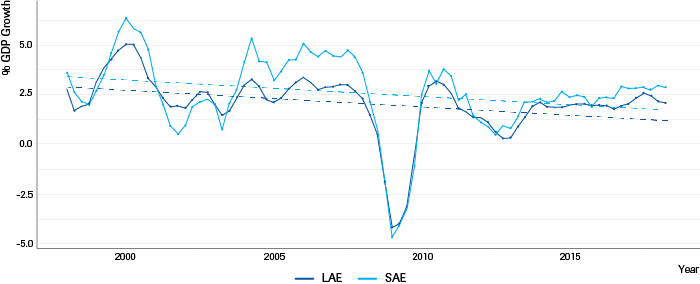

Even if ‘Paradise Lost’ is not the appropriate trope, ‘Paradise Fraying’ might be. There are at least a number of good reasons to wonder whether the golden age of small states might be over. As Janan Ganesh recently suggested—not without a hint of hyperbole—in the Financial Times: "Almost all the conditions that allowed small nations to bloom look precarious."[81] We want to emphasize, however, that most economic datasets do not (yet?) bear out that point. The remarkable streak of superior economic performance of advanced ‘small’ countries (of which the Netherlands is a ‘large’ one) over their larger advanced peers still endures.[82]

Source: Landfall Strategy Group

Findings from our broader and more geo-strategic datasets, however, do point to some worrisome trends that certainly deserve further in-depth analysis and policy attention.

4. Looking Ahead

4.1 What Do Our Data Project?

In the (recent) past, our contributions to the Dutch government’s Strategic Monitor have always dutifully reported on what we have called our ‘nowcasting geo-dynamics’ efforts—our attempt to leverage various new datasets to better monitor what has been going on in the international system beyond a few cherry-picked peak-events. The main intuition behind this ‘presentist’ focus was that we did not feel confident that we had the wherewithal to produce any evidence-based risk assessments about interstate conflicts.

This year, however, we did decide to leap beyond our previous comfort zone. Since last year we have been using various machine learning algorithms to provide forward-looking risk assessments of (intra-state) political violence at the national[83] and (in recent months) also sub-national levels. What we did this year, for the first time, was to expand these efforts to also include analogous models for interstate (militarized) conflict data. We trained[84] various models using a human-coded interstate conflict dependent variable (the HIHOST variable[85] from the Militarized Interstate Disputes dataset)[86] and a set of high-level CAMEO codes (e.g., ‘coerce’, ‘fight’, ‘threaten’, etc.) from the automated event datasets alongside the independent variables that MIDv4.2 itself used. To do this, we used H2O, a new and promising open source machine learning and predictive analytics platform, to train an ensemble of supervised machine learning models based on different algorithms.[87] The results we report here represent the average of the HIHOST scores the different models predict for a certain dyad. For a more detailed explanation of our methodology, please see annex “Events Datasets and Strategic Monitoring.”

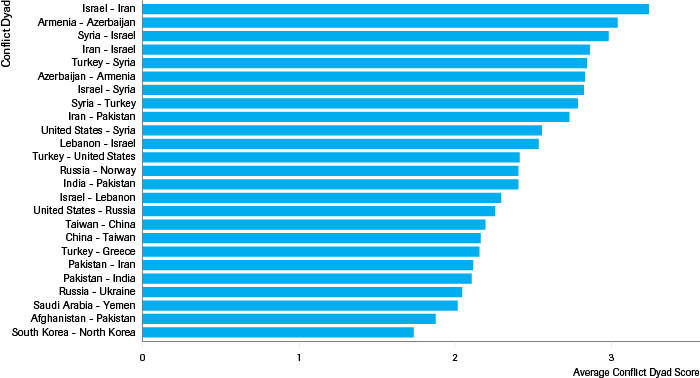

Dyadic Interstate Conflict Risk

Our first visual (Figure 27) presents the dyads that, based on our ensemble of models, appear the most risk-prone to become embroiled in higher levels of interstate conflict over 2019. This list, which was generated in a fully automated way based on the ‘best fit’ with the data, does seem to have quite some prima facie plausibility. The central role of the Middle East in the top dyads; tensions in the South China Sea or between India and Pakistan—most of these top-twenty risks will not surprise most pundits.

At the same time, however, this list also reveals a few dangerous dyads that are likely to confound many experts and would require further exploration and validation. These include the possible unfreezing of the Azerbaijan–Armenia conflict (which as a long-time frozen conflict does not receive much press attention, but where the political turmoil in Armenia after the election may be picked up by our models as a potential trigger for further escalation), Russia–Norway (probably a false positive triggered by NATO’s large-scale Trident Juncture exercise that took place in Norway, as well as Russia’s provocative reactions to it),[88] and others. Certainly the presence in this list of nuclear dyads—like the USA and Russia; India and Pakistan; the USA and China—may test the faith of many security analysts who put absolute trust in nuclear deterrence.[89]

Source: HCSS calculations based on GDELT (English and Translingual) and ICEWS

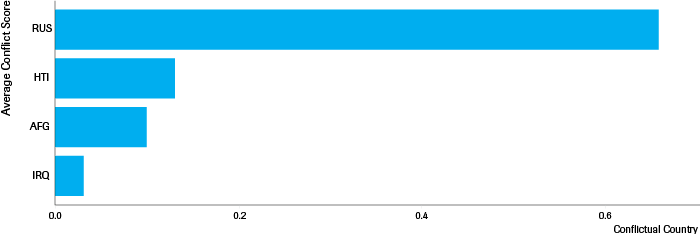

The Netherlands

Source: HCSS calculations based on GDELT (English and Translingual) and ICEWS

Based on our event datasets and the different machine learning tools we have applied to them, the countries with which the Netherlands is predicted to have the highest levels of interstate disputes are the Russian Federation, followed (at a long distance) by Haiti, Afghanistan, and Iraq. We note that the levels of intensity remain very low (below 1, which is the lowest level after 0), providing yet another confirmation of the relatively propitious position of the Netherlands in global geo-dynamics. What struck us in this finding was that, based on our data and models, Venezuela did not make the cut.

| Target Country |

Mean |

|---|---|

| RUS |

0.6600 |

| HTI |

0.1300 |

| AFG |

0.1000 |

| IRQ |

0.0300 |

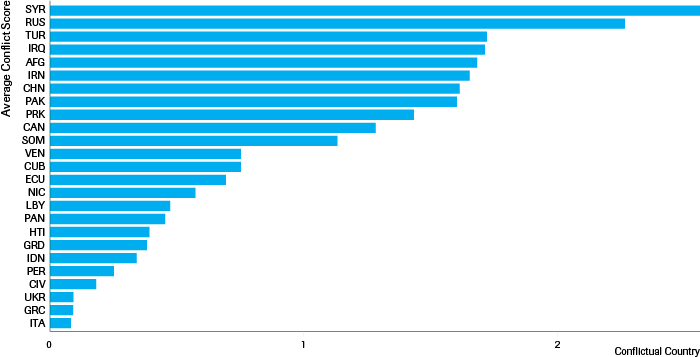

The United States

The map of the countries that the US is predicted by the models to have the highest levels of interstate disputes with over 2019 is significantly more expansive than that of the other countries we are reporting on—which reflects the country’s still unique position (and its reach and impact) across the international system. The actual levels of predicted militarization are significantly higher than those of the Netherlands.

Source: HCSS calculations based on GDELT (English and Translingual) and ICEWS

| Target Country |

Mean |

|---|---|

| SYR |

2.560 |

| RUS |

2.260 |

| TUR |

1.720 |

| IRQ |

1.710 |

| AFG |

1.680 |

| IRN |

1.650 |

| CHN |

1.610 |

For the US, the most conflictual dyad in 2019 is—arguably not very surprisingly—Syria, followed by Russia, but then followed (more unexpectedly) by Turkey and Iraq.

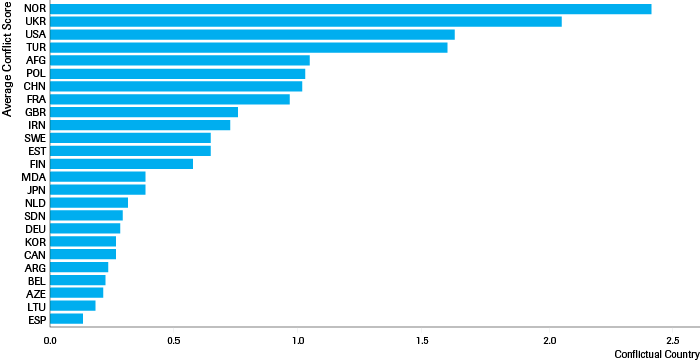

Russia

For Russia, the most dangerous dyads include Norway, immediately followed by Ukraine, but also quite a few other countries.

Source: HCSS calculations based on GDELT (English and Translingual) and ICEWS

| Target Country |

Mean |

|---|---|

| NOR |

2.410 |

| UKR |

2.050 |

| USA |

1.620 |

| TUR |

1.590 |

| AFG |

1.040 |

| POL |

1.020 |

| CHN |

1.010 |

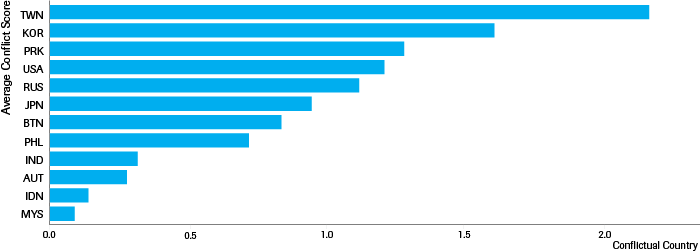

China

Source: HCSS calculations based on GDELT (English and Translingual) and ICEWS

| Target Country |

Mean |

|---|---|

| TWN |

2.170 |

| KOR |

1.610 |

| PRK |

1.280 |

| USA |

1.210 |

| RUS |

1.120 |

| JPN |

0.950 |

| BTN |

0.840 |

If we look at the countries that China, based on our models, is predicted to have the most intense disputes with, we find Taiwan in the top spot, followed by South Korea and then (much more surprisingly, though less likely) by North Korea. Curiously, despite Russia’s emphatic claims that it is re-orienting itself away from ‘the West’ towards ‘the East’, it turns out that our (early) models show Russia in the top five of candidates for dyadic conflict with China, immediately after the US.

4.2 What Do We Not Have (and Need to Build) Data on?

In our successive contributions to the Strategic Monitor of the Dutch government we have consistently argued in favor of a more systematically balanced and evidence-based approach to the analysis of international dynamics. Our early embrace of the new automated event datasets, that once again play an important role in this report, was an important component of this ambition. We hope to have demonstrated the (potential) added value of these more systematic efforts over—the far more common—purely anecdotal (cherry-picked) evidence. We find it hard to understand why, a full eight years after Philip Schrodt’s seminal paper on the promise of automated production of high-volume, near real-time international political event data,[90] not more progress has been made in this area and why—even more troubling from our point of view—Europe has mostly remained ‘missing in action’ on this front.[91]

We have always been acutely aware of the continued limitations of these automated event datasets—probably more so than most, precisely because we have been using them so extensively. Like at least some of our colleagues, however, we have been buoyed by the prima facie plausibility of many of the high-level findings that we have been able to extract from these datasets over the years and by our ability to improve the performance of our forecasting models by inserting the event data. Based on the unprecedented (and ongoing) improvements that are taking place in natural language processing and especially in machine learning more broadly, we remain confident the quality and scope of this effort are our single best hope to at least compensate for the many well-know limitations of human analysts.

Given the decidedly sub-optimal uptake of these near real-time (fully or semi-)automated datasets to date, our field endures to be stuck in a twilight zone between better validated[92] so-called ‘structural’ variables that tend to be produced and/or collated at least one and often even two years after the fact; and the near real-time, often highly mediatized and/or politicized event selection and interpretations of ongoing international developments by pundits of various ilk.

We may be emerging from the dark ages in terms of our actual ability to ‘monitor’ what is really happening internationally in a deeper and more evidence-based way. But we are still doing so at a glacially slow pace and in a disappointingly haphazard way. There remain myriad truly foundational aspects of the international system that we have not even come close to 'capturing'—or worse, have barely tried. We still sorely miss reliable systematic indicators for some of the more 'leading' (as opposed to ‘lagging') indicators, like countries’ detailed defense investment choices, their broader policy choices, etc. We also are in great need of better ways to track some of the ‘softer’ (but arguably increasingly more foundational and consequential) aspects of geo-dynamics, such as identitarian angst, liquid modernity, the transition to a post-industrial/post-modern world, potential (at least physical) de-globalization, shifts in what may very well become the ultimate ‘balance of power’ (between human and artificial intelligence, etc.).

5. Conclusions

5.1 Things May Not Be What They Seem

This next section provides a bird’s-eye view of our geo-dynamic findings for the different time windows for which we have data available in our StratBase. Table 1 provides this overview for: 1) all available dates (for the respective datasets, some of which go further back in time than others) up until November 4, 2018 (when the most of this report was produced); 2) the period from 1989 (since the end of the Cold War) until November 2018; 3) 2008 up until November 2018; (the past decade), 4) from 2016 to November 2019 (the past few years) and 5) 2018 (up until November 2018). The data are visualized in two ways. The arrows up, down or right represent the actual mathematical changes in the figures; whereas we also added the colors green and red to indicate which trends are ‘good’ or ‘bad’ for the user’s ease of absorption. We decided against purely displaying mathematical changes, as some changes are widely seen as ‘positive’ (e.g., economic growth, increase in the rule of law, etc.), whereas others are seen as ‘negative’ (increase in battle deaths, increase in CO2 emissions, etc.). Seeing so many arrows pointing up or down would therefore be extremely hard to digest, which is why we opted for this—admittedly Euro- or even Holland-centric—way of presenting our findings. The logic behind the color-coding is that green represents what we take to be dominant ‘Western European’ preferences: a more equitable world is preferable over a less equitable one; a more ‘relativist’ attitude towards religion is preferable over a more ‘fundamentalist’ one; nationalism and populism (“we first”) are more dangerous than multilateralism and open-mindedness, etc. The table specifies how we have color-coded each indicators. We recognize that these choices are to a large extent ethnocentric and not universally shared even in Western Europe or the Netherlands. We certainly acknowledge the potential disadvantages of excessive egalitarianism; the importance of respecting different values or interests; and the continuing grip that (also national) identity has on people in our own countries and across the globe. But all in all, we still submit that our choices contain a certain ‘logic’ that—while not universally shared—might still provide a useful cognitive ‘anchor’ for our readers to get a better feel for the big picture trends behind all of these data.

With this in mind, here is the promised high-level overview:

The high-level picture we therefore obtain here is a mixed one. The bottom-line trend is still, counter-intuitively, a positive one. Contrary to the growing sense of despair that global pollsters detect (and many of us may even feel), our data show the balance between ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ geo-dynamic trends to be improving over time for those time periods for which we have data on most indicators. This is especially the case for the most recent time windows, with almost twice as many improvements as deteriorations in the (admittedly limited) available indicators. The most striking finding is probably in the geo-economic category, which is often used by people to indicate that people’s lives are getting worse, but where we see mostly improvements across all time windows. The poverty gap is decreasing for the entire observed period despite the economic upheavals in the recent decades, and life expectancy is still increasing. Even for small advanced countries like the Netherlands the story remains robustly positive: they outperform the large ones for the overwhelming majority of reported time periods. While they tend to get hit harder in tough times, they also bounce back more quickly and are able to reach new heights.

We find a similar—though certainly less pronounced—positive trend in the international geo-political and geo-military categories, especially in the most recent time periods. We see more mixed scores in these categories than in the geo-economic one, but also more encouraging trends than conventional wisdom would suggest. While the number of factually assertive events in the military conflict domain increases, the average Goldstein score, depicting all events in all automated event datasets that are now used by HCSS, is improving, as is the number of ‘positive’ events (cooperation). These positive (green) trends are particularly noticeable in recent years.

In a number of other geo-dynamic categories, however, we observe more discouraging trends than one would gather from conventional wisdom. Many readers may be surprised that this is especially the case in the geo-societal category on ‘values’ issues, most of which tend to move away from post-modern Europe instead of getting closer. The level of generalized trust decreases for most regions of the world with the exception of the Old West. Although a visible improvement is present in the New West, the Reformed West[93] demonstrates an opposite trend. This decline in trust is accompanied by a decrease in secular and emancipatory values. Simultaneously, the willingness to fight for one’s country is diminishing, possibly signifying a rising demand for other solutions to conflicts and misunderstandings between countries.

The same is also the case for the—both international and domestic—geo-judicial and the domestic geo-political categories. For instance, corruption control diminishes for the high-income countries, which is less intuitively expected than for some other types of countries. Europe remains the only ‘stable’ region in this regard, improving its corruption control mechanisms while others have both ups and downs (and some regions exhibit a clear downward path). The ‘rule of law’ trend is negative for the lower-middle and low income countries, and positive for upper-middle and high income countries. However, the geographical breakdown of the same data reveals that the rule of law has actually been strengthened only in Europe and Central Asia, while the trend for all other regions is negative.

5.2 Making Sense of (Limited) Data and Missing Non-Data

Because of the importance of governmental decisions, and our limited capacity as human beings, government has a responsibility to use the most powerful tools at its disposal to make the best decisions it can. When policymakers make decisions without gathering all available information, looking at alternative courses of action, and anticipating the likely consequences of their actions, they are as foolish as someone who fails to consult a map when driving in unfamiliar territory. When governmental officials ignore the latest scientific developments, suppress new information, or make decisions that are rationalized after the fact, bad policy is made, resulting in loss of life, squandered economic resources, and the needless destruction of natural resources.”[94]

The most dominant—even purely visually—and disturbing finding in our overview table is probably the large amount of missing data.[95] The amount of available data of all sorts is exploding exponentially across the globe. We can now mine an avalanche of data in ever more sophisticated ways that are still improving by leaps and bounds. Yet our ability to monitor geo-dynamic trends remains extremely unbalanced, with rich, validated, regularly updated, and near real-time datasets on geo-economic issues; but with far patchier datasets on all other geo-dynamic categories. In a day and age when all advanced nations profess their aspiration to become more ‘evidence-based’ in policy-making, that chasm cannot but surprise. International economic and financial organizations like the World Bank, IMF, and OECD can only be applauded for their gargantuan efforts to collect and freely disseminate so many global datasets in their areas of competence. Certain parts of the UN system without a doubt also make valiant efforts in selected fields like demography. But there is no commensurate effort on geo-military data (e.g., by regional military organizations like NATO), or geo-judicial data (e.g., by international legal institutions—quite a few of which are located in The Hague).

Where does that leave us as we try to make sense of what we do and do not know from the point of view of international policy analysis and development? How are prudent strategic decision-makers supposed to leverage the both available and unavailable elements of the desired but still largely elusive ‘strategic knowledge base’ in their quest to come to actionable conclusions today?

Our personal sense—and it is not much more than that—is that the still fairly optimistic picture that this report has derived from different datasets is in some ways likely to be overly rosy. As our data showed, many of the ‘softer’ aspects of geo-dynamics, like the deeper undercurrents in terms of values, evoked some of the most somber of the results we examined. But there were also plenty of worrisome aspects in the geo-economic, geo-political, and geo-military domains. We suspect that part of the difference between the still relatively more optimistic portrayal of geo-dynamics that emerges from this report and the more outspoken geo-dynamic angst that permeates similar analytical efforts by many of our colleagues is due to the aforementioned uncaptured or poorly covered trends. It is increasingly difficult not to experience a deep and growing sense of unease when we hear the Russian leader talk about Russians “going to heaven” as martyrs in the event of nuclear war;[96] or the Chinese leader telling his military commanders to “concentrate preparations for fighting a war.”[97]

And yet we would still like to caution against excessively one-sided ‘doom and gloom’ thinking, since we also suspect that many of the insights we proffered in this report may ultimately prove to be overly pessimistic from a (broader) security point of view. We have not—in this edition (and to our great regret)—focused on what we have, in previous work,[98] called ‘the other (brighter) side of the security coin’.[99] The deeper wellsprings of (individual, societal, national, regional, even global) security arguably go much deeper than psychological or political grievances, however heart-felt they may be. The quote we used at the outset of this report referred to the fact that in 1858, British pundits were so engrossed in ‘geo-political’ developments in India and France that they entirely missed ultimately far more consequential (also in terms of security-relevance) ‘geo-hygienic’ developments like the building of the London waste management system that would end up saving the lives of millions of people across the globe. Today as well, the altercations and ‘near-misses’ between the Great Powers; the ambitions, statements, and peccadilloes of the ‘strongmen’ who lead them; the danger of all sorts of deliberate or involuntary (military) escalations are very real and understandably catch media headlines. But where do we read about the continued global decline in absolute poverty, the impressive strides that are being made in financial inclusion, in global education, in sustainable energy, in identitarian emancipation (with far less 'oppression' at the personal, group, and national level), in secularism, critical thinking, and also (once again, as in 19th-century Britain) in hygiene,[100] and what all of these trends mean for international security?[101]

In the absence of that more reliable, comprehensive, and ‘holistic’ evidence base that we feel is required in order to start generating truly ‘evidence-based’ international policy analysis, we want to conclude this analysis by highlighting two fundamental pieces of the international puzzle[102] that we may be misinterpreting. The first one of these is the resilience of the current international order(s). Most of today’s analysts tend to assume that the current international order(s) is(/are) fragile, and that strongman leaders’ clear intentions to 'shake up' the order(s) are fraught with unprecedented danger. At least some of us submit that this may not be the case, and that there are multiple grounds to assume that the world today is fundamentally different—economically, educationally, culturally, nuclearly, etc. We submit that the international order(s) is(/are) far more resilient than in 1914 or in 1933. The second one of these puzzle pieces relates to the 'efficiency' of the system as it emerged after the Second World War (Bretton Woods, UN, NATO, then EU, and 'formalistic' multilateralism, etc.). Here too, most of our analysts tend to assume that the current system still serves us well, as it at least 'embeds' (/bridles) our more vestigial, primordial ('realist') urges. This leads to a 'conservative realist' exhortation: "above all, let's not rock our all-in-all 'nice' boat—alternatives would be even worse." Also here—at least some of us think that may very well not be the case, and that the current 'heavy', formalistic, linear structures in which we have embedded ourselves lead to lowest-common-denominator equilibria and not to (positively) disruptive breakout solutions.