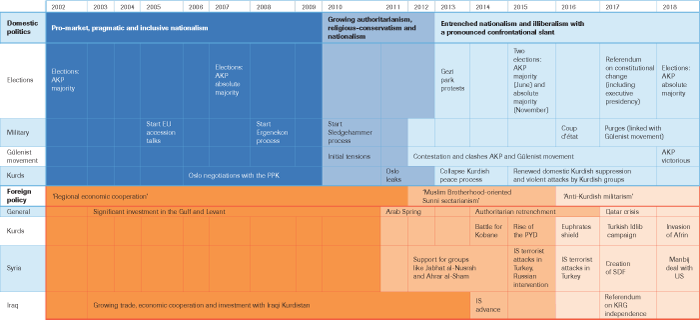

Exhibit 1: Turkish Foreign Policy towards Syria

The AKP established close relations with Assad’s Syria between 2002 and 2011 by eliminating visa requirements, increasing trade and holding joint cabinet meetings.[58] Despite close relations, then-Prime Minister Erdoğan did not conceal his sympathy for the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood (SMB) and even asked President Assad to legalise the movement (its leaders were in political exile in Turkey).[59] When the Syrian civil war broke out in 2011, Turkey’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Ahmet Davutoglu, called on President Assad to enact structural political reform, including integration of the SMB into Syrian politics. His efforts were entirely in line with Turkey’s broader pro-Muslim Brotherhood strategy in response to the Arab Spring, which was in turn enabled by the AKP’s own religious/ideological background, its transnational roots, and the scope that opened domestically for a more assertive foreign policy.

When President Assad declined the Turkish proposal, Ankara took a hard line and sought to overthrow his regime through a mix of international isolation at the diplomatic level and providing operational backing for the SMB and other Syrian opposition groups.[60] In 2011 and 2012, Turkey hosted several meetings to stimulate and facilitate the emergence of a Syrian opposition front in Istanbul and Antalya, namely the Syrian National Coalition (SNC) and its armed wing, the Free Syrian Army (FSA). While the SNC brought opposition groups of different political hues together (including SMB supporters), most of them shared a Sunni socio-religious background.[61] This enabled Turkey to pursue its interests along Sunni identity lines, grounded in its own Muslim Brotherhood antecedents.

A key problem of the early Western-Turkish-Gulf strategy in arming the Syrian opposition was that Western countries sought to make a clear cut between moderate FSA groups and more religiously oriented Sunni groups – supporting the former, but not the latter. In contrast, neither Turkey nor Gulf countries attached much importance to this distinction. In addition, even in the early days, differences between moderate and more radical groups, as well as between more secular and more religious groups were far from clear cut and intermingling had already started to occur. For example, about a dozen more religiously oriented rebel groups, such as Ahrar al-Sham, regularly worked with FSA groups in 2012/13 without accepting the authority of the FSA's Supreme Military Council. Although the US and Turkey were united in their covert effort to arm and equip more moderate FSA groups against President Assad’s regime, US officials especially warned Turkey against weapon deliveries to extremist groups in October 2012.[62] Despite occasional official Turkish assurances, it appears that Ankara continued to arm both moderate and more religiously oriented Sunni groups, sometimes under the guise of the SNC/FSA and at other times beneath the radar. A few incidents and developments provide suggestive proof for this assessment:

Turkey continued to support more radical groups via the SNC until at least September 2013, well after the initial US warning that in its view greater care should be taken in vetting FSA groups for support.[63]

A truck loaded with weapons was stopped in Hatay in January 2014. Although the Turkish government insisted that the truck carried humanitarian assistance for Syrian Turkmens, initial reports indicated that the truck was headed to Kilis, which is close to areas that were at that time held by jihadi’s.[64]

A month later, Turkish gendarmerie stopped a convoy of trucks that turned out to belong to the Turkish Intelligence Agency (MIT). The convoy was loaded with arms and on its way to the Reyhanli border crossing. At the time, the crossing was under the control of JAN.[65] Subsequent investigations indicate that the cargo was probably intended for JAN, Ansar al-Sham or other extremist groups.[66]

While the US branded JAN a terrorist organisation in December 2012, Turkey only followed suit in June 2014.[67]

Turkey only started to take control of its border with Syria more seriously in 2015 when the first IS attacks had taken place in Turkey and the YPG was on the rise after its victory at Kobane. This allowed thousands of jihadists to travel from Turkey into Syria under the pretext of providing humanitarian aid between 2011 and 2015.[68]

The growing dominance of IS in 2013 was not initially seen as a problem by Turkey, but it did create a further rift in the international approach to the Syrian civil war. Turkey’s top priority remained the overthrow of the regime of President Assad. Given the difficulty of engaging in a direct military intervention, its main tool to this effect was the somewhat motley assortment of FSA and more extremist armed groups.[69] However, the focus of the US and most European countries shifted to defeating IS and they came to see militant radical Sunni groups in an even more negative light than before. This ensured Ankara’s policy towards the Syrian civil war remained trapped between the conflicting requirements of maintaining good relations with the US (necessitating a strong stance against IS), encouraging the overthrow of President Assad (in which endeavor IS was a helpful, latent ally) and preventing the Kurds in Turkey and Syria from becoming too powerful or teaming up (the battles of IS with Syria’s Kurds were also helpful in this regard).[70] Turkey consistently prioritised the second and third objective.

In fact, Ankara only started to see IS as a serious threat towards the middle of 2014, when the group abducted (and later released) dozens of Turkey’s consular staff from its Mosul Consulate.[71] This incident played a significant role in convincing Turkey to join the US-led coalition against IS, although Turkey’s anti-IS efforts remained somewhat half-hearted. For example, although it agreed to stop the flow of foreign terrorist fighters as part of the Coalition’s strategy against IS,[72] Turkey’s claims of having put effective border controls in place continued to ring hollow as evidence kept surfacing that people, lethal military equipment, funds/resources and bomb-making materials continued to cross the Turkish border into then-IS strongholds.[73] Presumably, Turkey maintained its under-the-radar ‘supply policy’ towards the Syrian conflict, including engagement with more extremist groups, because it killed two birds with one stone: it strengthened anti-Assad forces and it disadvantaged the Syrian Kurds who were frequently engaged in battle with IS.

The result of this policy was a clear deterioration of Turkey’s relationship with both the US and the Syrian (as well as Iraqi) Kurds as the combat assistance Turkey could have offered in the fight against IS did not materialise. Moreover, by not putting effective border controls in place until late in the day, Turkey frustrated its Western allies and arguably prolonged the fight against IS.

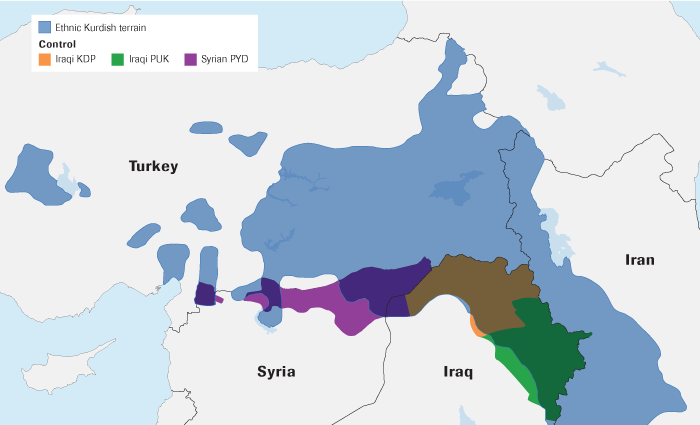

By 2014/15, the Syrian Kurds had emerged as the most effective force fighting IS. While the PYD’s territorial gains induced anxiety in Ankara, it kept diplomatic channels open with the head of the PYD, Salih Muslim, who sought to reassure Turkey that the PYD’s intention was to free the region from IS threat and not the establishment of an independent Syrian Kurdistan.[74] By mid-2015, the PYD’s armed forces, the YPG, had managed to establish three autonomous, but non-contiguous, cantons in northern Syria (Afrin, Jazira and Kobani) during their fight with IS. This brought into being a Kurdish ‘corridor’ that extended about 400 kilometres westward from the border between Syria and the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (see Figure 3). Practically, PYD control over hundreds of kilometres of border fatally undermined Turkey’s efforts to establish safe zones within Syria as a buffer against regime forces, reduce Kurdish influence and keep Syrian refugees inside of their country.[75]

Source: Middle East Eye; Institute for the Study of War.

The development caused deep concerns among the Turkish political and military elite, as they considered the YPG a PKK-linked terrorist group which in the medium term could develop the region into an autonomous Kurdish state (‘Rojava’). Memories of the 1980s, when the Ba’ath regime supported the PKK and allowed it to stage violent campaigns in Turkey from northern Syria, were quick to spring to mind.[76] Ankara’s attitude became even more hostile when the PKK – disappointed by the absence of structural reform and the clear failure of the peace process by mid-2015, inspired by the YPG’s successes across the border, and more confident of the political revival of the Kurdish cause following the June 2015 elections in which the HDP won about 13 per cent of the vote – initiated its ‘urban warfare’ strategy in Turkey to achieve ‘democratic autonomy’.[77] A vicious cycle of terrorist attacks and state terrorism ensued, which led to large-scale destruction and displacement in major cities in south-eastern Turkey. In this context, the Syrian Kurds were increasingly seen as a threat to national security and US assistance to the YPG as a source of major concern.[78]

In a bid to counter the PYD/YPG, Turkey deployed a three-dimensional strategy, namely exploiting intra-Kurdish leadership rivalry (especially by using President Barzani of the KRG against the PYD leadership), using the FSA against YPG forces and – as a last resort – employing its own military forces.[79] The limited impact of the first two planks of Turkey’s strategy soon became apparent when it launched three military operations in rapid succession.[80] These had the net effect of effectively containing the PYD/YPG along Turkey’s southern borders:[81]

In August 2016, a mix of Turkish and FSA troops took control of Jarablus and the Al-Bab border crossing (Operation Euphrates Shield). Turkish control over Al-Bab prevented the coalescence of the PYD cantons of Kobani and Afrin.[82]

In October 2017, Turkish forces created safe zones along Turkey’s southern border that further blocked the completion of the ‘Kurdish corridor’. Turkey also executed operations in and around Idlib as part of the Astana agreement to establish de-escalation zones. These allowed Turkey to surround the PYD-controlled Afrin canton from the south and prevent its expansion.

In January 2018, Turkish and proxy forces initiated an offensive that wrested control over Afrin from the Kurds (Operation Olive Branch).[83]

An interesting ancillary effect of Turkey’s increasingly anti-Kurdish foreign policy in Syria is that its success required improved relations with Russia given the latter’s dominance of the northern Syrian airspace from its bases in Latakia.[84] Although Presidents Putin and Erdoğan rapidly restored relations after the Turkish air force downed a Russian fighter in 2015 when it suited them, the price Ankara had to pay for Russian support was steep. In exchange for Russian consent for its operations in northern Syria and restraining the Syrian Kurds, Turkey became a full sponsor of the Russian-initiated Astana peace negotiations – increasing its legitimacy as an alternative pathway to peace next to the UN’s Geneva process – and had to accept, at least implicitly, that President Assad would continue to lead Syria.[85] In addition, by seeking Russian support for its intervention in northern Syria, Turkey also deepened its rift with the US. Ideologically, Turkey marketed these manoeuvres with reference to the newly-minted notion of ‘Eurasianism’, which was briefly discussed above.[86]

In brief, the domestic power consolidation of the AKP in Turkey enabled the party to engage in an ambitious revisionist effort of the regional political order when the Arab Spring broke. Initially, this took shape largely via support for Muslim Brotherhood-related groups. In Syria this meant Turkish support for an array of FSA (including the Muslim Brotherhood) and more radical Sunni groups. However, when the AKP-PKK peace talks collapsed and the AKP lost its absolute majority in the June 2015 elections, anti-Kurdish narratives and actions swiftly emerged as instruments to restore AKP domestic political dominance. This was both facilitated and necessitated by the PKK’s urban campaign of violence that followed the failure of the peace talks. Meanwhile, the rise of IS and, later, the Russian intervention in the Syrian civil war contributed significantly to the failure of Turkey’s initial strategy to overthrow President Assad by aiding and abetting a range of armed opposition groups. To revitalize this strategy, Turkey essentially turned a blind eye to IS, albeit for a limited period.

Exhibit 2: Turkish foreign policy towards Iraq

Turkish foreign policy towards Iraq between 2002 and 2018 focused largely on its relationship with the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) – the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) in particular. Turkey’s main priorities were, and continue to be, increasing its exports and maintaining KRG support in its fight against the PKK. On both counts, it has been rather successful. For example, towards the end of 2013 Turkey signed an energy agreement with the KRG that enabled oil to be pumped directly to Turkey to the volume of around 500,000 barrels a day (about one-seventh of total Iraqi exports).[87] In fact, Iraq was Turkey’s third-largest export partner between 2007 and 2016.[88] The scale of the successful economic Turkish-Kurdish relationship even replaced the longstanding Turkish policy of intolerance and animosity towards autonomous Kurdish regimes in its immediate neighbourhood.

In return, the KRG continues to allow several Turkish military bases to exist on its territory, as well as Turkish military operations to take place in northern Iraq that are aimed at limiting the PKK’s ability to manoeuvre, rest and recuperate.[89] The deeper explanation for the persistence of these bases and the apparent lack of intra-Kurdish solidarity lies in the complexities of Kurdish power politics. As the PKK consolidated its power in northern Iraq in the 1990s and aligned itself with the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK),[90] KDP-PKK relations suffered and a power rivalry emerged between them.[91] Turkey subsequently started to support the KDP-Peshmerga in their clashes with the PKK, as both the KDP and PKK claim the mantle of pan-Kurdish leadership.[92] Turkey is paying a price for this arrangement, however, as the Iraqi central government does not consider Turkish-KRG relations in a positive light and has accused Turkey of interfering in Iraq’s domestic affairs on several occasions.[93] Nevertheless, the cost of deteriorating relations between Turkey and Iraq has up to now been negligible for Turkey.

Several episodes suggest, however, that the relation between Turkey and the KRG is one of pragmatic convenience and skewed in favour of Turkey. For example, when the Iraqi Kurds came under attack from IS in 2014, the KRG leadership had expected greater Turkish support on top of what it received from its international partners.[94] Yet, Turkish assistance for the Peshmerga remained extremely limited throughout the entire fight.[95] The explanation for this lies in Turkey’s general ambivalence towards to the IS, which it did not initially see as a serious threat, and in Turkish long-standing conflict with the PKK, which it sees as linked with the Syrian YPG. Hence, in 2014 Turkey launched a military training programme for the Peshmerga forces of Iraq´s Kurds rather than providing direct combat support. This introduced a somewhat sour note into Turkish-Kurdish relations, especially when the IS onslaught intensified. President Erdoğan’s termination of the Turkish-PKK peace process in 2015 provided a second note of discord, in part because it was followed by a resumption of air strikes against PKK positions in northern Iraq. Finally, the rhetoric of Turkey’s political leadership turned sharply against the KRG when it went ahead with its ‘independence referendum’ in September 2017.[96] Ankara considered independence as materially different from autonomy and viewed an independent Kurdish state in northern Iraq as a dangerous precedent for Turkey’s own Kurds. Once the Iraqi government had called its wayward Kurdish region to order, Turkish-KRG relations resumed rather quickly, however, suggesting that the failure of the Kurdish independence bid had produced no lasting damage.

On balance, it can be argued that positive relations between Turkey and the KRG (especially the KDP) represent one of Turkey’s more notable foreign policy successes in the region. As it stands, the KRG is now almost wholly economically dependent on Turkey, which means it must continuously take good note of Ankara’s strategic policy preferences. It is worth noting that the creation of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (2003–05) predates Turkey’s reinvigorated anti-Kurdish strategy of 2015 by a significant period. This makes it an exception to Turkey’s current aggressive approach towards the PKK and YPG. Dealt the ‘bad hand’ of Iraqi Kurdish autonomy, which it could not control, Turkey played it well by encapsulating the KRG in its sphere of influence, which was greatly facilitated by intra-Kurdish tensions between the PKK and KDP.

Exhibit 3: Turkey’s position amid Iranian – Saudi rivalry

After the AKP had more or less consolidated its control over the state, Turkish foreign policy gradually complemented its traditional European orientation with a greater focus on the Middle East. Turkey successfully played to the interests and issues of key regional players with its mix of trade/investment and politico-religious moderation/modernisation. The groundwork for this approach had been laid by Ahmet Davutoglu and it enabled positive sum economic thinking to guide Turkish foreign policy for some time, i.e. the exercise of soft power based on mutual economic advantage. This approach enabled Turkey to maintain positive relations with both Iran and Saudi Arabia until 2011 – no mean feat.

For example, a Turkish-Saudi Business Council was established in 2003, with mutual visits between the respective heads of state further increasing cooperation. Turkey and Saudi Arabia also saw eye-to-eye politically on a range of issues including Palestine, Lebanon and the Kurds while they both opposed the Iranian nuclear energy programme and its regional expansion.[97] Turkey nevertheless also engaged in mediation efforts between Iran and the West in respect of the former’s nuclear programme. This resulted in a joint declaration between Turkey, Brazil and Iran in 2010 that aimed to mitigate Western concerns as well as forestall sanctions.[98] Furthermore, when NATO deployed missile defence systems to Turkey in 2010, the latter sought to reassure Iran by announcing that the systems were meant solely for defensive purposes.[99] In short, Turkey tempered global realpolitik with the pragmatism of good neighbourliness based on an economic foundation.

Yet, as noted, the Arab uprisings saw the AKP leadership engage in an ambitious effort to socially engineer the regional political order and make good on ‘the regional shift towards political Islam’ that it saw occurring with Muslim Brotherhood-inspired parties coming to power in Egypt and Tunisia.[100] Qatar rapidly became Turkey’s new ally – the pair being united in their support for the Muslim Brotherhood-variety of political Islam – and together they energetically backed the Ennahdha Party, the Egyptian Brotherhood, Hamas and Brotherhood-related parts of the Syrian uprising. The Turkish-Qatari romance was symbolised by the creation of a Turkish military base in Qatar in 2014.[101] Predictably, these moves earned Turkey the enmity of Saudi Arabia, for which both the Muslim Brotherhood and Iran represented ‘the source of all evils’ in the Arab world. In fact, Saudi Arabia outlawed the Muslim Brotherhood as a terrorist organisation in March 2014.[102] The rift was further deepened when Turkey maintained its Qatari alliance after the latter’s quasi-expulsion from the Gulf Cooperation Council in 2017, and pragmatically used the blockade’s economic consequences for Qatar to offset some of the financial losses resulting from its deteriorating relationship with Saudi Arabia.

Turkish-Iranian relations fared somewhat better after 2011 due to their common rejection of Kurdish aspirations for greater autonomy. Just as Turkey perceives the PKK as a terrorist organisation, Iran views its Iranian offshoot, the Free Life Party of Kurdistan (PJAK),as a terrorist group. Both countries view the PKK’s Syrian offshoot, the PYD, in a similar light.[103] Aligning with Iran offered Turkey an opportunity to counter-balance the PYD in Syria despite longstanding Iranian support for the PUK and its links with the PKK. Apart from these more structural elements, Turkey and Iran were also nudged towards each other by the behaviour of third parties, notably the US. For example, the aggressive US policy towards Iran, combined with US-support for the Syrian Kurds, facilitated an interest-based cooperation between Iran and Turkey.[104] The official visit of the Iranian Chief of Staff, Mohammed Bagheri, to Turkey in August 2017 suggests that such collaboration continues to expand.[105]

On balance, it is clear that Turkish-Saudi and Turkish-Iranian relations have largely been a function of shifting Turkish foreign policy towards the Middle East – from regional economic cooperation towards an assertive pro-Muslim Brotherhood, pro-Sunni policy in the wake of the Arab Spring, the effects of which were moderated only in the case of Iran by a shared anti-Kurdish interest in Syria.