Mopti: A contested space

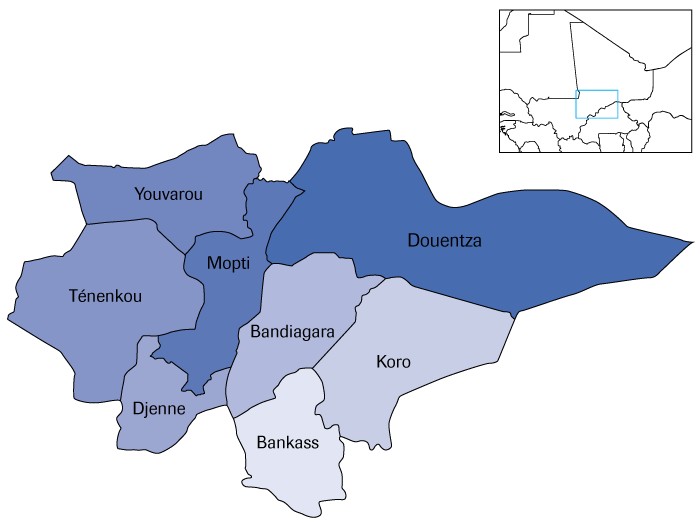

Mopti is the fifth administrative region of Mali and is divided into eight cercles and 108 communes.[2] It is bordered by the Tombouctou region to the north, the Ségou region to the southwest and Burkina Faso to the southeast. Located in the inner Niger Delta, an area known as Macina, home to a network of lakes, swamps and channels, it is one of the most fertile areas in Africa. For centuries, the inhabitants of the region have benefitted from and valued Macina’s wealth of resources. As one customary chief explained, ‘God created a hundred fortunes and he only left one on earth for humankind to enjoy: water. That is why we never have to drag our feet here in Mopti’.[3]

Bestowed with abundant natural resources, then, and situated on one of the main waterways in West Africa, the inner Niger Delta has been an important trade hub throughout history as well as a highly contested space. Between the 9th and 16th centuries, the area was incorporated within the great West African trading empires in control of the north-south axis of trans-Saharan commerce.[4] The main products exchanged along this route were salt, manufactured goods, gold and slaves.[5] By the 17th century, the route moved westwards, following the European settlements on the coast and the new transatlantic and north European trading routes.[6]

Originally inhabited by the Nono and the Bozo people, the indigenous cultivators and fishermen of the region, the commercial activities of the inner Delta attracted and assimilated many other ethnicities into the trading activities of the region. Although the region was part of different West African empires, its unification as a state came only in the 19th century. Between 1820 and 1862, the entire inner Delta was unified into a theocratic Muslim state known as the Dina, or Macina Empire, under the rule of the Fulani marabout Sékou Amadou.[7] However, the relative stability of the Dina did not last long. It was overthrown by new competitors, including French troops that colonised the region between 1894 and 1960. To date, the inner Niger Delta remains a contested space in which various groups coexist and exploit abundant natural resources.

Socio-professional groups

In the central regions of Mali, the livelihoods of local populations and production systems are closely linked to natural resources – land and water in particular.[8] Here, socio-professional groups[9] that largely overlap with the ethnic groups resident in the centre of Mali[10] exploit these resources within three production systems.[11] For instance, the Bozo ethnic group is associated with fishing activities and with both sedentary and nomadic ways of life, depending on the availability and access to waters rich in fish. The Dogon, the Bambara and the Songhai have a sedentary agricultural mode of subsistence, and cultivate millet, sorghum and rice, as well as onions, tobacco and peanuts. The Fulani and the Tuareg are known as a nomadic ethnic groups of pastoralists who move their herds across the regions they inhabit in search of better grazing and watering for their animals.

The activities of all these groups take place by following natural cycles. During the dry season, herds of cattle are led by pastoralists on to grazing lands rich of bourgou, a grass typical to the inner Delta that thrives in inundated areas.[12] Once the inner Delta is flooded during the rainy season, usually between June and September, pastoralists move their cattle to dry lands towards the south or east of the Mopti region. At the same time, agriculturalists cultivate the flooded zones with rice and millet and harvest them between September and November. Fishermen set their nets on the channels (mares) that are flooded by the river Niger and abundant in fish. When the water recedes, it leaves behind fertile lands suited for both agriculture and pastoralism. This is also the time that pastoralists can return their cattle in the Delta, according to a well-established calendar and order.[13]

Traditional management of natural resources

Traditionally, most natural resources exploitation takes place based on a complex management system that is the legacy of the Macina Empire (1820-1864) created by Sékou Amadou. During his reign, Amadou elaborated a resource management system to end the numerous intraethnic conflicts among Fulani populations and to regulate access and use of resources in the Niger Delta. This system of governance, which came to be known with the same name as the state – the Dina – built on existing norms of allocation and management of natural resources that date back to early history.[14] Drawing on principles of Islam, the Dina led to nomadic populations becoming sedentary, regulated the seasonal movement of herds, and divided resources between pastoral (nomadic) and agricultural (sedentary) groups.

Perhaps one of the most important transformations brought about by the Dina was the centralised management of access and use of resources that represented a shift of power from nomadic to sedentary groups. As one scholar puts it, ‘every square meter of the Delta and its neighbouring lands had an owner and a manager’.[15] Routes into and out of the Delta were delimited, dry season itineraries were identified and the order in which herds crossed into pastures and entry-exit points were clearly sanctioned.[16] In its heyday, the Dina integrated all natural resources of the Delta into a centralised administration overseen by the Dina Council in Hamdullahi, linking agricultural, pastoral and fishing activities across production systems and ethnic lines. It established a set of rules that provided clear boundaries for local producers and clarified rights and duties for every production system. This strong codification created ‘a mutual expectation of positive performance’ for all socio-professional groups by which a breach of reciprocity may result in mutually destructive competition and conflict.[17]

The centralisation replaced the previous relative autonomy of different production systems with a dependence on the Dina state for access to resources and conflict mediation. In the process, some authority figures were violently dispossessed of their roles. New managers were put in place and given the power to overrule community decisions regarding the management of resources. This is also the time when the figure of the dioro (jowro) was introduced as a master of the land, charged with its management.[18] The dioro continues to play a key role in granting access pastures in the Delta today.[19]

Under the Dina, the allocation of resources was based on kinship, blood relations and long-term residence; access was awarded in accordance to a person’s social status according to a strict hierarchy.[20] At the community level, the Dina state ensured the enforcement of these consistent rules and the functioning of dispute resolution mechanisms administered by customary authorities, including heads of communities and councils of elders.[21] The appointment of chiefs seems to have been a prerogative of Sékou Amadou. Given the reliance of the central system on these actors’ compliance and competence, the central power gave incentives to maintain loyalty to the code. For instance, Amadou would reward those who supported him in battles, members of his family, and those ‘obedient to the Dina’ with chieftaincies.[22]

Whereas implementation of these rules and the functioning of the production economy required goodwill and cooperation,[23] the Dina state did not shy away from using its standing army to enforce its decisions.[24] Overall, it became an ‘ecological and economic project in which an incessant power game was played over access to natural resources’.[25] This power play led to the empowerment of certain groups and to the political marginalisation of others – a phenomenon not very different from contemporary dynamics. Some of those who were discriminated against include Fulani pastoralists who did not immediately accept the new management system.[26]

Parallel management systems

The fall of the Macina Empire in 1864 in the wake of local uprisings against it was followed by a colonial administration that managed the region until 1960. The French divided the region into thirty-five cantons and appointed chiefs of cantons which were subordinated to the chiefs of subdivisions (Macina, Ténenkou, Mopti and Djenné), who were in turn subject to the decisions of the chiefs of cercles at the time (Issa Ber, Mopti and Macina). Only the chiefs of cantons, the lowest rank, were locals.[27]

As a general rule, the colonial administration accepted the indigenous management of natural resources, namely, the Dina, but undermined its ability to enforce access to rights and to administer local resources based on the needs of various production systems. For instance, the colonial power was convinced that some of the lands that were used only seasonally were underexploited. In 1904, this assumption led to the transfer of ownership of unoccupied lands to the state (via nationalisation) and later to their allocation as private property.[28] The colonial administration also imposed itself as an external actor managing and distributing access to natural resources in the Delta. For the first time, the Delta was no longer managed by a political and economic structure based on the interests of local populations and their customs. Instead, an outsider entity began governing both access and use of natural resources.[29]

This marked the outset of two parallel forms of land tenure, whose existence feeds directly into the insecurity of tenure that characterises Mopti today. Customary chiefs could only manage the lands under continuous production; the colonial administration was charged with the management of unoccupied lands and was allowed to grant private property titles. Other resources such as water and forests were simply taken off from the jurisdiction of customary systems and placed under the control of the Water and Forests Agency, the predecessor of what is nowadays called the National Direction of Water and Forests (Direction Nationale des Eaux et Forêts).

Most local populations remained largely ignorant of this dual system and of the legal provisions adopted by the French administration – as they remain about land tenure legislation today.[30] However, some of those who did know did not shy away from exploiting the new system to gain advantageous access to resources. The creation of local interest groups intent on exploiting the French administration for preferential access to productive resources denied to them under the customary system (especially for settlement), continuously undermining the traditional management of natural resources. Rather than addressing the exclusionary practices of the Dina, the colonial and postcolonial rearrangement of resource management continued these practices.

In postcolonial Mali under the presidency of Modibo Keïta (1960–1968), customary systems underwent further alterations and saw their power diminish even more, moving into the hands of state authorities.[31] The cantonment chiefdoms were abolished because they were perceived as supporters of the opposition party.[32] The administrative division of the region was rearranged and following a governmental policy all administrators were recruited from outside the Mopti region. The role of the administration was to maintain social order and arbitrate disputes through the chieftaincies, who were likewise charged with tax collection. In spite of this proliferation of authorities, little clarity was established as to what exactly each authority was responsible for.

The most emblematic example is that of the Water and Forests Agency, which enjoyed power to arrest, confiscate and impose sanctions on local populations, as well as to influence the distribution of natural resources. Seasonal visitors to the Delta could now request access to natural resources from traditional chiefs, the administration (e.g., governor) and its technical service (Water and Forests Agency) – that had competing interests. Finally, in 1986 all customary land tenure rights were abolished and property was transferred to the state. Customary property rights were converted to rights of use of the land ‘only for as long as the state has no need of it’.[33] According to the most updated legislation, unclaimed land belongs to the state, but customary property rights are recognised if ratified by formal authorities.[34]

The state added competing and overlapping institutions, which, instead of creating links with the local knowledge of production systems, challenged and undermined it. Production systems are currently faced with a governance characterised by ‘structural chaos’.[35] There is a vast array of state institutions that local communities cannot rely on and that compete in allocating natural resources, generating more tenure insecurity. A case in point is the use of formal justice in the management of natural resources that often led to inapplicable and unsustainable decisions that in turn were conducive to local conflict.[36] For instance, judges attributed property rights to outsiders from different cercles, even different regions of the country, which contravenes customary norms.[37] This solidified in the reattribution of land to members of a certain community by traditional chiefs while an outsider held the property title.

More generally, local populations did not trust judges to solve their disputes because the judges did not understand local dynamics and their verdicts tended to favour the richer party and sedentary groups.[38] Discrimination against pastoralists was mentioned by a number of interviewees. In particular, one explained that ‘the formal justice has brutalised and abused the Fulani pastoralists for too long’ and that ‘injustice never ends against them’.[39] In addition, formal justice often struggled to fulfil its mandate. It lacked resources – mostly qualified personnel – and collaboration with the police was not always smooth. Often the statements collected by the police were poorly redacted and lacked basic information.[40] Judiciary proceedings were also perceived as being too long: some of the cases brought before judges needed immediate solutions to ensure the continuity of activities of various production groups, for example the permit to start the seasonal movement of herds.[41]

In retrospect, nationalisation has deprived local communities of their customary jurisdiction over communal resources. Nowadays, a legal framework applies to the entire country without accounting for local contingencies, and conventions regulate the management of natural resources.[42] In Mopti, the new laws cut across customary frontiers established by the Dina and made outsiders with little knowledge of local production systems responsible for administering regional wealth. This is not to say that state legislation should be regarded as intentionally inimical towards local communities and their working systems. But the way in which it was implemented in Mopti was incoherent and conducive to marginalisation, subverting customary management of natural resources without putting in place a sustainable alternative or complementary system to the satisfaction of local constituencies. Even when moves to support traditional arrangements were made, they never resulted in actionable plans or the devolution of power.

Challenges to traditional justice as resource management

The legacy of the Dina empire is still visible in the Mopti region. Indeed, the implementation of Dina norms is perhaps the most unifying factor across production systems and ethnic groups today. Customary chiefs play a prominent role in solving disputes based on Dina principles, especially given the overwhelming absence of the formal justice system and people’s mistrust towards the judiciary.[43] Customary leaders are commonly perceived as part of society, not as external actors seeking to impose a different order on the community and its resources.[44] Within all administration systems that succeeded the Dina in Mopti, traditional chiefs were the only constant authority figure and the only one stemming directly from the community.[45] These authorities thus derive legitimacy from their proximity to the disputants, physically and culturally, who view them as ‘pillars of the society’, and as the only ones who can maintain the social fabric of central Mali.[46] At the same time, however, these traditional authorities face an erosion of their legitimacy and their ability to adjudicate resource conflicts.

Structural impediments

The decentralisation process that started in 1992 could have been a positive turning point for the better management of natural resources.[47] In this process, the state sought to formalise the ties between formal local authorities and traditional ones, for instance, by formally appointing chiefs. Most important, customary authorities are invested by law with reconciliation in civil and commercial matters.[48] Many customary chiefs objected to how decentralisation unfolded. First, they did not appreciate that in the decentralised hierarchy of governance they were subject to the authority of the mayors, mainly because traditional authorities were only granted a consultative voice.[49] In their view, this limits their role and subjugates their decisions to the executive power of mayors who are bound to consult chiefs, but not to implement any of their suggestions.[50] Formal authorities agreed in interviews that the more the state apparatus evolved, the less important traditional authorities became.[51]

The roles that chiefs were granted were crafted in such a way that the impact of their decisions could not go beyond their village and could only be implemented with the consent of state authorities, that is, mayors.[52] This limited their ability to generate legitimacy and social capital via leveraging their social embeddedness.[53] Additionally, in certain cases, the multiparty system that results in partisan allegiances in the communal council prevented chiefs from being asked for advice. Often mayors of municipalities (communes) that encompass several villages invite for consultations only the chiefs who either belong to the same political party or have views that align with their own.[54] As a consequence, ‘chiefs have a very important role on paper. But in reality, they are not even consulted’.[55]

Another dissatisfaction stems from the selective implementation of the renowned 2006 law relating to the creation and administration of villages, fractions and districts. Given the multitude of tasks allocated by the state to these traditional authorities, the law legislated that chiefs and their councillors were entitled to financial compensation and reimbursement of travel expenses.[56] Most of the chiefs and councillors interviewed never received either. Most municipalities justify the lack of enforcement by pointing to their depleted treasuries, but to the chiefs this is the umpteenth proof of the state’s unwillingness to genuinely insert chieftaincies within the local power structures and acknowledge their role in local governance.[57]

In practice, and even though each village, fraction or neighbourhood is administered by a chief assisted by a council, the precise status of chieftains is still unclear. Even when laws grant responsibilities to chiefs, they are hardly put in the position of fulfilling them. Although the selection and nomination of the chiefs is to be carried out based on local traditions, a local representative of the state has to ratify the nomination within thirty working days. This process is particularly consequential given that, by law, village chiefs have a consultative voice in the communal council and need a formal recognition to be able to exercise their duty.[58] The vast majority of chiefs – up to 70 per cent – did not receive formal recognition by the state as required by Malian law.[59]

The nominations process has also been challenged in recent years. According to tradition, the chieftaincy is passed from father to son. If the son is too young, authority should be passed on to the next closest male relative. If no one meets the standards, sometimes the state administration organises elections, challenging centuries-old traditions of succession.[60] Such new protocols are harmful and fall short because they are self-centred and remote from the normative values in which local populations recognise themselves.

Corruption and misgovernance

The involvement of chiefs in the political arena – often expressed by allegiance to certain parties – and corruption are two of the main circumstances delegitimising customary authorities today.[61] According to a Malian expert, customary chiefs are related by family ties to the mayors and state authorities in at least 60 per cent of the 703 communes of the country.[62] This number is a personal estimate, but every chief interviewed affirmed that they were either closely related to the mayors in their villages or towns or had occupied both positions at the same time at a certain point. Village chiefs started running for mayors’ seats in the aftermath of decentralisation.[63] More of a preservation strategy than a political agenda, this practice evolved into the concentration of power in the hands of few, which in turn consolidated patronage systems that, when proved disadvantageous for local communities, become harder to break and to challenge.[64]

Local chieftains are deeply involved in politics and often members of political parties.[65] Whereas in principle no one should be banned from expressing their political preferences in public, this situation creates a legitimacy problem. Believed to be super partes authorities, the inclination towards a specific political agenda undermines their impartiality. People fear that they might make decisions either in favour of villagers who are members of their political party or in line with partisan choices.[66] People are also under the impression that chiefs sometimes collude with formal authorities in the settlement of disputes. For instance, according to local users of customary systems, in certain cases traditional authorities have agreed with the gendarmerie on a fine they have then shared between themselves.[67]

Additionally, the proximity of the customary figures to political parties may play a role in their decisions to attribute communal resources such as land to people outside the community.[68] The main external contenders to land in the centre of Mali are private investors and the bourgeoisie bamakoise, the new rich from Bamako.[69] Most of the outsiders who seek property titles in Mopti are farmers, thus limiting the amount of pasture available for pastoralists. But agriculturalists are affected as well. Some complain that the best parcels of land are sold to investors, with or without the consent of the chiefs, and that the customary norms are overridden in these transactions.[70] Newcomers to a community do not owe allegiance to local chiefs or to customs that apply there. Because customary norms that dictate use of land are applicable to and known only by the local community, an outsider’s use of communal resources cannot be administered by local chieftaincies.[71]

Furthermore, if they are not directly involved in the decision to sell land to outsiders, customary authorities are also frequently bypassed during the processes of subdividing and selling land, even though the law requires their consultation.[72] They are also not informed of such transactions carried out by formal authorities, which increases the risk of mismanagement of local resources (by way of reattribution) and consequent conflict.[73] This has already resulted in pitiless competition over natural resources and conflicts that often escalated into communal violence.[74]

Rent-seeking behaviour

Another delegitimising element is the rent-seeking behaviour of certain customary figures, among which the dioros, the landlords of the bourgou.[75] The bourgoutières, the zones where this fodder grows, are particularly important for the pastoralist production system, which was prioritised in these zones under the Dina. Second in line were the Bozo, who could use it to establish a basis for their fishing activities in the Delta. Finally, agriculturalists (mainly rimaibes, the slaves of the Fulani) cultivated these lands and harvested them before the return of the pastoralists.[76] However, the bourgoutières came under remarkable pressure as society became more sedentary and harvesting increasingly important relative to grazing. Moreover, the overlapping and contradicting management systems created tensions and conflicts with regards to ownership and use.

To date, a good portion of the bourgoutières in the rural areas are managed by the dioros, just as they were in the time of Sékou Amadou. However, permission to graze in a bourgoutier has become conditional on paying a fee.[77] The fee used to have the symbolic function of acknowledgement of local dioros and their authority by outsiders. In exchange, the dioros used this as a monitoring system to ensure that they knew who entered the area and that no one was seeking illicit appropriation.[78] However, current amounts go far beyond the symbolic value and vary mainly based on the number of heads in the herd and on the zone. In certain areas in the north of Mopti, the dioros used to demand up to five million CFA (about 7700 euro) to access their bourgoutières.[79] In other zones, they demanded one million CFA for every hundred animals, even if they did not have enough pasture for them.[80] Estimates from previous studies in the area indicate that annual profits from bourgou fields vary from USD 170 per hectare under rudimentary management to USD 750 per hectare under intense management.[81]

This rent-seeking behaviour pushed many pastoralists to fraudolently enter the bourgoutier, which led to the dioros having them sanctioned by the gendarmerie.[82] Dioros were also accused of complicity with formal authorities, including the justice system.[83] However, being brought before the formal institutions of the state is perceived as humiliating by the Fulani community and the population living in the rural areas.[84] As one interviewee emphatically explained, ‘if you bring me to the police for a dispute and I am married to your sister, I will divorce her and never speak to you again’.[85]

When formal justice is sidelined, it is often because its legal framework fails to provide ‘an answer to the psychological and cultural expectations governing the confidence of litigants and the (formal) law’.[86] This is also symptomatic of a justice system that is remote from its users both physically and (most importantly) psychologically.[87] Thus, the rent-seeking behaviour of the dioros and their collaboration with formal institutions who have historically mistreated local populations, was perceived as one of the gravest forms of social injustice.

Lack of enforcement and a complementary justice system

One final factor undermining the legitimacy of customary authorities and their ability to mediate resource conflicts is that they have no enforcement power.[88] Indeed, the resurgence of resource conflicts in Mopti is symptomatic of precisely this lack and of the grave absence of justice that should accompany reconciliation. Although disputants might personally share the decisions of customary authorities, they cannot be legally or in any other way compelled to implement them.

The only enforcement mechanism available to customary authorities is to cultivate a good reputation and maintain constructive relations with the community.[89] Often the act of abiding by customary decisions is driven by communal social expectation and fear of social sanctioning – for example, individuals can be excluded from social events, like marriages and baptisms. Although this does not resolve all commitment problems, having customary authorities able to impose visible social costs on perpetrators helps the ‘hand-tying’ and enforcement.[90] However, this contrepoids system characteristic of traditional arrangements, however, has eroded and lost its power over time.[91]

Moreover, the disputes are not mediated at the level of socio-professional groups that compete for natural resources and do not ensure the buy-in of all competing parties. Usually, disputes are handled on an individual basis and the chiefs take into account the particular episode that triggered the dispute, but not always the entire history of conflict in that particular community or related to that specific resource. The reconciliation is also between the disputants only, not between the local socio-professional groups they are a part of and a justice process does not accompany it. Such conflicts thus continue to arise.

The lack of enforceability of their decisions had pushed those wealthy enough to afford the costs of the formal justice to seek redress before the judiciary.[92] But, as mentioned, this contributed to the further degradation of communal relations, rather than to just outcomes. ‘Formal justice only speaks the truth when one pays’, ‘the independence of the judiciary means the absolute lack of control over justice’, ‘judicial power equals economic power which equals corruption’, and ‘formal justice is just another name for repression’ are some of the impressions that interviewees expressed.[93]

Conclusion

This chapter demonstrates that local governance mechanisms have proven unable to prevent the increased escalation of these natural resource conflicts in Mopti. The process of colonialisation and postcolonial decentralisation had created a local resource governance system that involves many authorities whose competing and overlapping mandates often resulted in chaos rather than order. In addition, both formal and traditional justice mechanisms have often proven unable to mediate the existing resource conflicts effectively and to bring justice to their victims. On the one hand, formal justice is commonly perceived as expensive, lengthy, corrupt, unaware of local norms and dynamics, and abusive. On the other, customary justice often lacks enforcement power and the necessary state support to implement decisions that could prevent the (further) escalation of conflict. As the next chapter shows, this situation created fertile breeding ground for the incursion of radical armed groups.