Crisis Group aptly describes the Syrian conflict as ‘a constellation of overlapping crises’, of which each global, regional and sub-national dimension requires a calculated response that is part of a coherent broader framework.[6] This report articulates the Syrian conflict’s overlapping crises in terms of the most important negative consequences expected to develop or escalate as a result of the Syrian regime’s tacit victory in the conflict.

The regime’s military victory has been increasingly likely since Russia intervened on its behalf in 2015. However, it is important to understand that the regime’s victory will be a phase of the conflict’s evolution, not its ending. It may last for a year, a decade, or a generation, but it will not mark an end to the conflict unless old and new conflict dynamics are adequately resolved.

The precise nature and extent of the Syrian regime’s victory remains to be determined as it depends on regaining territorial control over Idlib and the north east, as well as on the outcomes of the political tracks and reconstruction processes the regime is currently pursuing on the international stage, with close assistance (and pressure) from Russia.

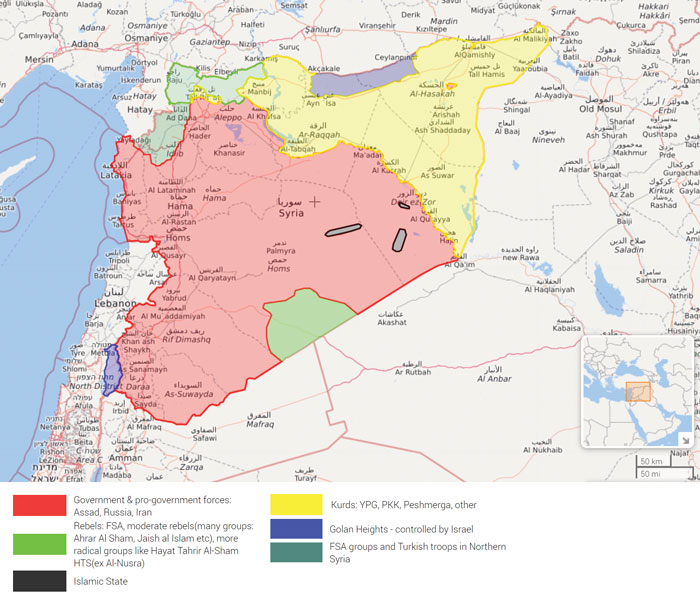

The two most likely scenarios for a regime victory are ‘frozen conflict’ and ‘reconquest’. In the ‘frozen conflict scenario’, several important areas of Syria maintain a degree of security, political and economic autonomy, while the Syrian regime re-entrenches itself more deeply in most of the country. For now, these regions would comprise the roughly 30 per cent of the country that the regime is yet to regain control over, namely Idlib (controlled mainly by Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham and Turkish forces/proxies), the Turkish-occupied areas in the border region, and what remains of the autonomous Kurdish areas in the north east of the country that are controlled by the Democratic Union Party (PYD), Syrian Democratic Council (SDC) and their armed forces. The future of these areas is largely dependent on Russian-Turkish relations and priorities. In the ‘reconquest scenario’, the Syrian regime re-entrenches itself over all of Syria, relying on various political and military deals to enforce its control.[7]

In both scenarios, the Syrian regime remains dependent on Russian, Iranian and Hezbollah’s political and military support, and will require vast amounts of investment and assistance – roughly four times its annual GDP – to conduct the extensive reconstruction needed in the country, where roughly one-third of infrastructure has been completely destroyed or severely damaged.[9] Without such reconstruction and structural humanitarian and development assistance, the living conditions of Syrians will deteriorate and come to constitute a protracted and extreme humanitarian disaster. The chance of conflict relapse and refugee flows will increase in the near future, due to mounting socioeconomic pressures.[10] Additionally, in neither scenario is the US likely to re-engage with the Syrian conflict in a way that gives it direct leverage over the decision-making of the regime. Faced with this reality, the EU and its member states will need to establish strategic policy objectives and put concrete mechanisms in place to deal with the Syrian conflict as a matter of urgency, if only to mitigate several of its negative externalities.[11]

In order to set meaningful objectives, it is crucial to understand the political economy of the regime that will drive these externalities. Establishing this is largely a matter of logical induction: with little access to the black box of the regime’s operating procedures and internal decision-making, the material realities of its day-to-day governance are the key evidential base from which the regime’s internal order can be reconstructed. Nonetheless, there is a growing pool of research that helps us to understand the regime’s operational priorities and practices, which largely fall into three realms: security, civilian affairs and political economy.

The regime’s dynamics in the realm of security have shifted significantly as a result of the conflict, as the nature of intervention by international actors supporting the Syrian government created major discontinuities in how the Syrian state exercises power that will continue to influence its short- to medium-term practices. This is unlike the realms of civilian affairs and political economy, where conflict dynamics since 2011 rather constitute an extreme amplification – and not a rupture – of pre-conflict dynamics in Syria. The following sections expand on the dynamics in each of these realms.

Security practices: state autonomy and networks of influence

Since 2011, the Syrian regime’s practices of political and military authority through its security services and armed forces have transformed significantly, mirroring the erosion of the regime’s autonomy and territorial sovereignty. This is evident in its reliance on Russia and Iran’s military, economic and political support, but also in its foreign policy orientations.[12]

The Russian, Iranian and Hezbollah interventions on behalf of the Syrian regime have been the most important source of autonomy and sovereignty erosion since 2011. While they helped overcome the Syrian armed forces’ existing organisational fragmentation and operational weaknesses in the short-term, they simultaneously undermined its central command structures. However, these interventions were critical for the Syrian regime’s survival and continue to be critical for its maintenance / re-establishment of territorial control, including in Idlib and the north east.

Whereas Syria was previously a prime example of a ‘shadow state’ – where power practices were dominated by security services and fear constituted a major incentive for compliance – it is now also a ‘transactional state’, in the sense that regime power practices are contingent upon transactional alignment with influential domestic factions (war profiteers and entrepreneurs of violence) that often benefit from support from external players, primarily Russia and Iran.[13] In the context of this dependency, governance is approached by the Syrian regime as an expression of an existential struggle in which force serves to defend existing institutional set-ups.[14] This has two implications: first, the transactional nature of the regime’s stability makes it fundamentally unstable in the sense that its longevity depends on its ability to continue to successfully leverage transactional relations and compromises with Russia, Iran and Hezbollah in a context of domestic power networks that mix competition with cooperation. Second, this means that should the transaction-based façade of stability falter, the regime is likely to fall back on its modus operandi of using force to defend its institutions. In the latter scenario, the only thing that would hold the regime back from using excessive force is a lack of capacity, not a lack of willingness to use violence.

Russia’s influence on the Syrian regime is primarily seen on the level of state institution-building, whereas Iran also practices influence outside of the state’s institutions. What complicates this further is that Russia and Iran have a Janus-faced relationship of collaboration and competition, each pushing for its own political, security and economic priorities. In order to understand the direction these transactions might take, an understanding of Russia and Iran’s interests in Syria is paramount.[15]

From the Russian perspective, Syria is one of the key arenas in and from which it poses a challenge to the traditional geopolitical dominance of the US in the Middle East. Russia wishes to promote its international image as a great power, able to manage and resolve the Syrian war, something the US has been unable or unwilling to do. Russia also portrays itself as being in a more legitimate position than the US since the Syrian state ‘invited’ Russian assistance in the first place. In this, Russia has also sought to directly undermine the UN-led political processes by creating parallel tracks such as the Astana process, which ultimately aim to present the UN with a fait accompli.

With regards to the domestic make-up of Syria in the short- to medium-term, Russia seeks to uphold the principle of the supremacy of state sovereignty by supporting the Syrian state over informal power structures linked with, but not part of, the state. Apart from its general support for the regime, this is evidenced most clearly in its specific efforts to re-establish central authority over the Syrian armed forces and other institution-building activities it has engaged with.

On the Iranian side of the equation, political interests also revolve around the projection of influence in Syria and the wider region in both soft-power terms (as leader of the resistance against the US and Israel) and in terms of real on-the-ground influence. Syria has been an important strategic partner for Iran against Israel, as well as against US influence in the region, which they view as ultimately aimed at regime change in Iran. Within this, protecting and expanding its access to proxies (most importantly Hezbollah in Lebanon) by securing and expanding friendly land and air territory, has been critical in Iran’s Syria approach. Since the 1980s it has sought to build bottom-up legitimacy through the infiltration of state institutions and Shi’a religious shrines, as well as establishing a lasting presence of sub-state armed groups that could outlive the Syrian regime in case of its collapse. Iran’s model of influence in Syria fundamentally relies on infiltrating the state, both by developing parallel institutions and by cultivating deep grassroots support (a strategy of questionable viability in a Sunni Muslim-majority country). For both Russia and Iran, war profiteering in terms of testing capabilities and weaponry have also played a role, although this is less relevant to the higher political dynamics of the conflict.

Throughout the war, the structure of the Syrian armed forces has been profoundly altered by two interlinked developments that emerged as a response to the severe gap in the regime’s military capacity to confront the opposition: a) interventions by foreign states on behalf of the Syrian regime, and b) the creation of so-called pro-regime militias – non-state actors beyond the official command structure of the Syrian armed forces – which can be Syrian or foreign (such as Hezbollah, or various Iran-linked units).

The rise of pro-regime militias has led to much concern and speculation among Western policy makers about the future of their relationship with the regime. Thus far, the regime has partially integrated select militias into its forces while allowing others to maintain operational autonomy (although not strategic autonomy). Pro-regime militias broadly align with the regime’s objectives within Syria. The regime’s ability to curb and/or instrumentalize militia profiteering and abuse of power will clarify their future power relation and (inter)dependency over the months/years to come.

Russia, Iran and Hezbollah[16] are playing a long game in Syria, with the regime trying to act as a referee that plays each side off against the other as much as possible. Even though Russia’s push for a strong, central state and Iran’s push for maintaining sub-state armed groups seem in conflict, from the perspective of the Syrian regime they are not necessarily mutually exclusive options. While the regime wants to restructure its army into a coherent force, it does not wish to disband pro-regime militias altogether because these do not (as yet) interfere with the work of the Syrian army and provide a useful force multiplier – coercive mechanisms with a degree of plausible deniability. As such, Hezbollah’s current expansion in Syria does not appear to be an issue for the regime. Moreover, the Syrian regime does not appear to be concerned about the projection of autonomy. Rather, it knows that, given its manpower shortages, it needs the support of Hezbollah and other pro-regime forces to maintain local security in the short- to medium-term. Ultimately, the geopolitical and strategic environment in which the Syrian regime operates is very volatile, so antagonizing any of the forces sympathetic to it is very risky.

Within the Syrian armed forces, corruption, profiteering and sectarianization are the three key dynamics that feed into negative externalities in the short- to medium-term. Corruption and profiteering are largely condoned by the Syrian regime since they fill a resource gap; as a result of mounting economic pressures, the salaries of members of the Syrian armed forces are low. Through corruption and profiteering, for example by Hezbollah-led arms and drugs smuggling networks, various local branches of the Syrian armed forces are able to supplement their meagre government salary with additional income, often merely through condoning the presence of smuggling routes or securing vehicles’ transition through certain areas. The sectarianisation or tribalisation of the Syrian armed forces manifests itself mainly in the presence of more Alawis than ever in army ranks. In practical terms, this is largely because Syrian law dictates that priority is given to the families of martyrs in filling government vacancies. But sectarian and tribal aspects, which also existed prior to the conflict, have been reinforced and today provide a strong identity marker for both inclusion and mobilisation. Depending on the geographical region within Syria, the regime plays on religious, ethnic or economic identities to play various local groups off against each other, while also claiming to represent all Syrians.

Syria’s security services have always been critical to regime survival, including under Assad Senior.[17] Recently, the Syrian regime has been overhauling its security services by appointing new loyalists to senior security positions. These are previously unknown individuals (such as the new head of military intelligence Kifah Moulhem and the head of the political security directorate Nasser al-Ali[18]) who became infamous through their role in escalating violence after 2011, and over whom the regime holds significant leverage in the form of corruption files. Thus, within the broader dynamic of Russian-Iranian competition over the design of Syria’s security landscape, to a degree the Syrian regime is asserting its own direction.

The initial purpose of Hezbollah’s intervention in Syria was to avert a crisis; if Assad fell, its ability to secure weapons and funding via/from Syria would be severely threatened. After the Russian intervention in 2015, Hezbollah’s involvement shifted from serving as offensive forward units for urban warfare to consolidating its positions in the south and south west of Syria. Having Assad run Syria is much more beneficial to Hezbollah than having to secure areas by themselves.

Hezbollah is currently pursuing three efforts in Syria.[19] First, it is securing smuggling networks and routes from southern Lebanon into rural Damascus, Dar’a and Sweida, and into Jordan and the Gulf. Its positions are largely along the Lebanese border, stretching from Western Homs and Quseyr to the Golan Heights. They maintain no visible presence here in the form of checkpoints or bases with Hezbollah flags but maintain small units that conduct monitoring and intelligence gathering and are on standby.[20] They do not interfere much with civilian life. In northern rural Damascus, Hezbollah is establishing entrenched positions similar to those it maintains in southern Lebanon. Secondly, it is working with Syrian regime security forces, such as the 7th division. This enables Hezbollah to maintain relatively low-level visibility as it is these regime forces that typically run checkpoints. In return for financial rewards, they allow Hezbollah personnel and goods to pass through the checkpoints unhindered. This enables Hezbollah to focus on its third effort, which is to set up positions to open up an eastern front against Israel. This would enable them, at some point, to draw pressure away from the Lebanese-Israeli border and towards the Golan Heights when needed.

While it is safe to assume that Hezbollah will maintain a permanent presence in Syria, albeit likely on a rotating basis, it is unclear to what extent Hezbollah will succeed in leveraging local support. For instance, despite a degree of reconciliation, several former rebel groups oppose Hezbollah’s expansion and have allegedly been involved in the overt obstruction of convoy movements and several targeted assassinations of Hezbollah personnel. In addition, the pool of recruits it can tap into remains small since Hezbollah is Shi’a and is not deeply embedded in local Syrian communities.[21] As a result, it is more likely that Hezbollah’s local support base will remain transactional and tacit, contingent upon the profits these supporters can earn.

Furthermore, its forces in Syria are unlikely to be brought into the central command structure of the Syrian army for several reasons. First, Hezbollah’s presence has always been independent of the Syrian armed forces and its forces are ideologically separate from the Syrian regime. For Hezbollah, Syria is a vehicle towards a greater end; a piece in the larger puzzle of its broader resistance struggle. Second, Hezbollah usually relies on a strictly horizontal command structure. In the Syrian case, there has been a higher command, but this has mostly been in charge of strategic decisions and weaponry such as long-range missiles. Local commanders receive general instructions, but they are allowed room for manoeuvre within these. Small units within Syria (typically consisting of 40–50 people) are assigned a local commander who is himself supervised by a Lebanese commander. This means that the existing operational command structures are antithetical to any central command structures in the Syrian armed forces. Third, Hezbollah is financially independent of the Syrian regime, meaning that even if the regime wanted to integrate Hezbollah, it has no leverage over the group. In the long-term, pro-regime militias are likely to either attain legal status as paramilitary forces or be integrated into the Syrian army.[22] As one analyst suggested, for Hezbollah forces in Syria this could amount to a Hashd al-Sha’bi style Iraq solution.[23]

In summary, the Syrian regime’s security practices will continue to revolve around force and the arbitration of uses of force, through which its institutional power is protected. As a result, national autonomy and sovereignty are likely to be partially conceded as long as operational support from Russia, Iran and Hezbollah is required and can be maintained. Within this space, the regime is likely to continue to enable profiteering dynamics between factions of the Syrian armed forces and non-state armed groups. Both constitute a deeply pragmatic approach to the maintenance of power in Syria.

Civil practices: exclusion and persecution

The second realm in which the Syrian regime asserts power is that of civil practices. Since October 2018, the Syrian Constitutional Committee has come to the forefront of political reform efforts. Despite the regime’s opposition to opening dialogue on its constitution, Russian pressure eventually brought it to the table. This dialogue is a critical component (together with packaging the regime’s stance on refugees) of Russia’s strategy for re-establishing Syria’s international legitimacy and its bidding for reconstruction funds. The first round of the process elicited few notable outcomes as trust in the regime among other participants remained low, and Assad himself maintained a non-committal stance to the process, commenting that ‘the Syrian government is not part of these negotiations nor of these discussions,’ and that its delegation ‘represents the viewpoint of the Syrian government’ but cannot bind it to any decisions.[24]

Although officially convened under the auspices of UN Security Council Resolution No. 2254, the constitutional reform process has thus far neglected to integrate or even initiate other requirements of 2254, including a permanent ceasefire, an end to targeting civilians, unimpeded humanitarian access, free elections, safe and voluntary refugee return, and genuine political transition. The neglect of these other elements, many of which constitute the root grievances that brought Syrians to the streets eight years ago, is a source of great frustration for Syrians.[25]

Regardless of the degree of success of the constitutional reform work, it represents only one part of the larger political resolution required to generate lasting conflict resolution. That larger process, which at a minimum would include planning for elections and transitional rule, is absent – not least because achieving any meaningful political progress is likely to mark the beginning of the end of the Syrian regime, at least in its current form.

This is not to say that genuine constitutional reform is an unworthy pursuit. As a Syrian lawyer has argued, the country’s constitution weighs in extreme favour of centralised presidential power over any other branch of government, even the legislative and judicial branches.[26] This was for instance aptly underlined in March of this year when a large portrait of Bashar al-Assad appeared on the main court of Tartous with the caption ‘First Judge’. Moreover, the Muslim-Arab patriarchal nature of the Syrian state is manifested in the constitutional requirement to have a male Muslim president.[27] Political life remains heavily in the hands of the Ba’ath Party and its loyalists despite, for example, some wartime concessions to the Syrian Social Nationalist Party.[28]

Ideally, therefore, the work of a constitutional committee would feed into a critical element of the political process Syria needs: building a new social contract. However, the reality of the regime’s civil practices suggests a grim reality in the short- to medium-term. Exclusion and persecution were key regime mechanisms in countering dissent, and there is no evidence that it plans to scale down these mechanisms.

One of the most acute matters affecting Syrians living inside Syria and refugees looking to return, is fear of persecution for avoiding military service. The Syrian regime continues to need emergency conscripts, for which it appeals to the military service law. In 2018, 400,000 names (including some that had allegedly been listed for amnesty) were called upon to serve.[29] There have also been reports that reconciliation agreements have included agreement to forcible conscription.[30]

A recent report on Sednaya prison sheds light on how detention and torture undermine the very fabric of Syrian society. The report found that detainees were overwhelmingly young, educated Sunni men, more than 90 per cent of whom reported having been tortured while in prison.[31] Only 5.5 per cent of detainees interviewed were tried according to the Syrian Penal Code (compared with more than 60 per cent before 2011). Individuals were prosecuted on a limited and specific set of articles from the Syrian Penal Code: membership of prohibited parties or associations (37.9%), weakening national sentiment or inciting racial or sectarian strife (21.2%), and broadcasting false news abroad (12.1%). Since 2011, trials based on the counter-terrorism law of 2012 have been extremely common. It was also found that detention had negatively affected the future employment of 67.8 per cent of detainees due to the associated stigma and the large role of the public sector in offering employment opportunities.

Pre-uprising Syria was a place of grim political repression, but it also featured a modicum of religious and ethnic pluralism, albeit discriminatory. More specifically, different rights and duties existed according to a person’s religious identity and ethnicity based on relations with the regime and its perception of a particular socio-ethnic group. The same remains true after years of war. According to the constitution, the supreme ethnic identity in Syria is Arab. Others are tolerated to varying degrees, or almost totally forbidden, such as the Kurdish identity.

Syria’s mainstream opposition parties have failed to articulate an inclusive definition of citizenship and an inclusive governing alternative that could mitigate the fears of minorities, secularists, and other marginalised segments of society – including Sunnis who opposed the Assad regime but felt excluded from the Syrian future envisioned by the organised opposition.[32] For this reason, Syria’s mainstream opposition parties have never gained the inclusive appeal of the initial protest movement, which gathered large sectors of the Syrian population from various backgrounds, and whose ideas represent a progressive and positive vision for Syria.

The Syrian regime’s practices of exclusion and persecution underline the fact that Syrian society is now more socially, politically and geographically fragmented than ever before.[33] None of the social problems that caused the 2011 protests have been resolved.

Economic practices: neoliberal resurgence and new cronyism

The above mentioned developments and issues are linked with the regime’s growing patrimonialism in terms of both citizenship and the economy, including flourishing, regime-linked smuggling networks. Patrimonial practices include loyalty demands from the regime’s cronies in return for economic privileges such as: the allocation of import rights, selective privatisation and private investment;[34] illicit drug and oil trade; and the smuggling of goods and people – in other words a ‘free-for-all’ in which the Syrian state does not engage in structural economic policies, but thrives on economic informality and illicitness.[35] As a result, wealth inequality is greater than before 2011.

According to one analyst, these economic patterns demonstrate that the regime is ‘shifting its nihilistic campaign of self-preservation from the military arena to the economic one’.[36] In other words, its basic instincts for survival at any and all costs are being ingrained in the country’s economic institutional infrastructure. This has led to a number of dynamics, including sanction-evasion mechanisms; dependency on external investment and supplies; the decline of value-creating sectors such as manufacturing and agriculture; new cronyism; and general neoliberal resurgence.

The Syrian regime is able to partially circumvent international sanctions by ‘creating new institutions and companies and relying on individuals to carry out economic transactions on the international market’.[37] In other words, important economic activities that would suffer under sanctions are delegated to individuals and companies that fall beyond the remit of sanctions. For this reason, a well-resourced mechanism with adequate intelligence that can be rapidly adjusted and updated, is paramount for the enforcement of sanctions. These regime-linked figures also engage in circular loans systems (via Russia) to circumvent sanctions.[38] In a recent interview, Bashar al-Assad appeared to boast about this situation, claiming that ‘most recently, in the past six months, some companies have started to come to invest in Syria. Of course, foreign investment remains slow in these circumstances, but there are ways to circumvent the sanctions, and we have started to engage with these companies, and they will come soon to invest.’ He added: ‘But this doesn’t mean that the investment and reconstruction process is going to be quick, I am realistic about this.’[39]

This circumvention of sanctions is marginal compared with the economic benefit the Syrian regime would enjoy were sanctions completely lifted. In other words, despite such measures, sanctions still exert significant pressure on the economic manoeuvring abilities of the Syrian regime. Reliance on investment is increased by the decline of value-producing domestic sectors, primarily manufacturing and agriculture. Joseph Daher notes that many manufacturing tycoons left for political and/or financial reasons between 2012 and 2015 and have since set up successful businesses in other countries. For example, the textile baron Mohamad Sharabati from Aleppo has re-established his business in Egypt.[40]

Moreover, since 2016, the Syrian regime’s political-economic strategy has been based on public-private partnerships, with the privatisation of economic sectors previously controlled by the state. Although liberal-sounding, privatisation is bound to benefit the private business networks of the regime since Syria is a cronyist economic marketplace, not a free one. This situation exacerbates the Syrian regime’s direct financial dependency on Iran and Russia, be it in the form of direct cash transfers or investments from private Iranian and Russian businesses.

Cronyism has become even more entrenched in Syria’s political economic dynamic. Prior to 2011, a degree of tacit or implied loyalty was expected in return for economic privileges from the regime. Since 2011, the expectation has been proven loyalism. According to Joseph Daher, the regime’s patrimonial nature was reinforced as its popular legitimacy diminished. Before 2011, those who were politically neutral or belonged to the liberal middle class were also included in regime networks. This is no longer the case. As a result, the network of businessmen linked to the regime has shrunk and demands for political allegiance have become much more aggressive.

In sum, the Syrian regime’s practices are informed by its own priorities as well as three pressure points, all of which are classic manifestations of hard power: internal security (for which it relies on Russia, Iran and Hezbollah); international alienation (which it seeks to remedy through normalisation with the help of Russian guidance in various diplomatic tracks); and financial (international sanctions it seeks to lift and contributions from key cronies it seeks to keep in line). The regime’s practices are not informed by soft power practices such as negotiation or diplomacy. Instead, it broadcasts propaganda through the channels it controls to assert its identity on its own terms.

Regime practices are also not informed by any serious consideration of international legal pressure or pursuit of international human rights norms. As a result, it has become virtually impossible to hold the Syrian regime to account or push it towards compromise based on soft power. In the security, civil and political economic practices that are at the heart of the six negative externalities discussed below, hard power plays a dominant role. This presents the EU and its member states with the uncomfortable reality that influencing the short- to medium-term future of the Syrian people can only be achieved through the practice of hard power, either directly through avenues of political, military and financial pressure, or indirectly through dialogue with and influence over those actors that already hold a significant degree of hard power-driven influence over the Syrian regime (primarily Russia and Iran). At present, this toolbox is only available to the EU in the economic sphere – and only to a limited extent.

Finally, and most importantly, the Syrian regime’s tacit victory as neither a ‘benign belligerent’ nor a legitimate post-conflict arbiter poses unprecedented challenges to the EU and its member states. As such, the focus of any ‘post-conflict’ stabilisation or development efforts in Syria cannot take the traditional route of state-centrism, either in the form of stabilisation or state-building.[41]

Zooming in on the political economy

The sheer magnitude of the cost of Syria’s war in economic terms has been clear for a number of years, although precise figures remain difficult to come by. The World Bank has estimated that the country experienced a cumulative GDP loss of 63 per cent between 2011 and 2016, and that reconstruction costs constitute a minimum of EUR 200 billion.[42] An estimated 11.7 million people within Syria are in need of assistance.[43] The Syrian pound has collapsed and is at its weakest point in history.[44] Among the problems related to this economic deterioration are public health crises, unemployment, and dependency on food aid.

Syria’s pre-war structural economic inequality has become even more entrenched in the country’s institutions and practices, such as the new cronyism, sanction evasion mechanisms and selective reconstruction efforts.

These dynamics are encouraged by the regime’s key allies and investors, who are likely to profit from the fractured economy both in the short-term (through the supply of labour and goods) and in the medium to long-term (through appropriating shares in Syrian state assets – for example as Russia has done in the country’s oil and gas resources and planned Russian and Iranian leases of a commercial sea port in Tartous and Latakia).[45] Short-term measures by its allies, such as the reported doubling of Iranian oil shipments to Syria between April and September 2019, have helped the Syrian regime avoid further deterioration in some sectors.[46] Nonetheless, severe fuel shortages in government areas have paralysed economic activity.[47] Now that the conflict has drawn to a slow close of sorts, it is in the economic arena that the nature of the Syrian regime manifests itself, and it is from this arena that many of the negative externalities discussed below emerge. Concretely, economic deterioration and fragmentation have had four significant consequences.

Looking ahead, the Syrian regime’s economic practices are the most important determinant of the degree of economic deterioration and fragmentation facing the country.[50] External factors such as sanctions and Lebanon’s economic health also play a role (since Lebanon is the source of the dollars used to buy imports).[51]

The current state of reconstruction is an important factor in Syria’s economic deterioration. On the one hand, without equitably distributed, socioeconomically responsible and politically sensitive reconstruction efforts, sustainable economic development is doomed to fail. On the other hand, however, reconstruction as it stands – regime-led, selective and lacking any external oversight or enforcement mechanisms – is doomed to exacerbate the exact tensions that sparked protest in 2011. This is especially the case since the areas worst affected by war are those urban areas – such as Aleppo, Douma, Deraa, Deir al-Zour and Raqqa – that were in the crossfire between various groups.[52] The political and socioeconomic security and stability of these areas is paramount to the security and stability of Syria as a whole. In order to achieve this, the wartime damages that reconstruction should address are threefold: physical infrastructure, human capital, and economic activity. At present, there are no serious efforts in pursuit of this.

Much of this has to do with the Syrian regime’s limited opportunities for financing reconstruction. With Russia and Iran unwilling and unable to foot the bill for the country’s reconstruction, the Syrian regime has come to rely on public-private partnerships from non-Western investors. Together with Law 10, these partnerships have created space for lucrative real estate contracts with large companies and projects that mainly build houses for the middle- to upper-class residents in selected areas.[53]

Looking ahead, due to prevailing warfighting conditions, there is little incentive for the Syrian regime to decrease either the elevated patrimonial demands of its cronies or its tolerance of illicit economic networks, since it derives political power and financial dividends from both. It is likely that the regime will deepen its connections with loyalist cronies, solidifying a small but potent domestic legitimacy base. This will make the Syrian state structures even less flexible towards political dissidence or dialogue, and will deepen the pre-war practices of economic inequality to the benefit of regime allies. As a result, both in political dialogue and representation and in economic influence and means, Syria will become significantly less diverse. This draws into serious question the degree to which, if a settlement were reached in the first place, any constitutional reform or political reconciliation efforts are likely to translate into improved material realities in Syria.

Moreover, there cannot be any stability in Syria unless refugees and internally displaced people (IDPs) are able to return in a voluntary, safe and dignified manner. This cannot be guaranteed unless there is a safe domestic environment, achieved through a robust political process with clear goals and mechanisms of enforcement and evaluation. Creating the opportunities for refugees and IDPs to return is a technical and economic necessity for reconstruction, since there are far too few young Syrians in the country to meet the labour demands of reconstruction. Even if temporary labour from abroad is used to fill this gap in supply, reconstruction is a long game and requires decades of investment by individuals committed to remaining in the country and building its future.

Additionally, since the new wave of urbanisation is occurring in the context of extreme socioeconomic inequality and social fragmentation, segregation is likely to become institutionalised in the gated communities, heightened security, surveillance systems and private security mechanisms that exist in many of the world’s most unequal cities on the one hand, and the aforementioned slums on the other.[54] The emergence of these types of infrastructure will magnify divisions in Syrian society and increase the pressure-cooker effect. The same mounting inequalities and tensions led to the 2011 protests in the first place and, as long as they continue to exist, can only be subdued through continuous suppression.

An informal regime adviser told Crisis Group that there is ‘no clear thinking in Damascus about the way forward. The problem is that the war cost the regime its brightest people, and if you think that current decision-makers are dogmatic, wait until you see those who will come after them.’[55]

In short, a combination of factors – including: the patrimonial, security-focused and identity-conscious nature of the Syrian regime; the reduced autonomy of the Syrian state; the conflicted situation on the ground; Iran’s potential to act as a spoiler vis-à-vis Russia’s stabilisation plans; rising international pressure on Iran; and popular resentment of Iran among Syria’s Sunnis and Alawites – means that Syria is likely to enter a lengthy and precarious post-conflict period in which all pro-regime stakeholders will vie for advantage through regime-linked networks while the priorities and needs of the Syrian population – at home and abroad – are largely ignored.