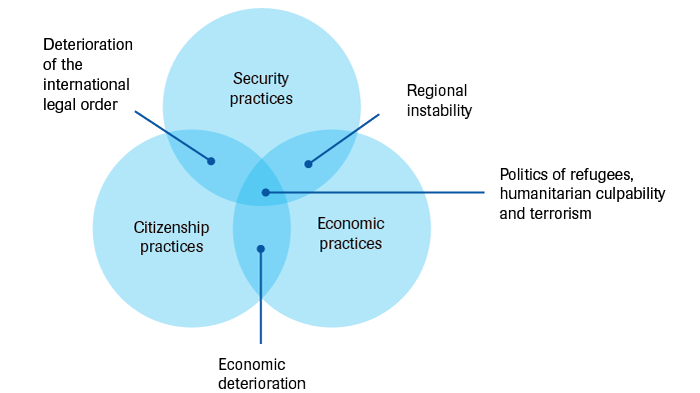

The sections below explore six negative externalities that are currently unfolding and/or likely to unfold in the short- to medium-term as a consequence of the Syrian regime’s retrenchment and practices in the areas of security, civilian affairs and the political economy. These negative externalities are largely produced, or escalated, by the regime’s security, civil and economic hard power practices (Figure 2 below). They all influence each other. Realistically, therefore, isolating externalities is possible in theory but less so in practice.

Risk of conflict relapse due to economic pressures

The aforementioned economic deterioration and fragmentation are likely to be characterised, in the short- to medium-term, by widespread wealth inequality, rapid urbanisation (including a resurgence of urban slums), illicit economic networks, and the further demise of value-generating sectors – many of the conditions that caused conflict to break out in the first place, only even more extreme.[56]

This means there is a significant risk that economic conditions will cause a relapse into conflict. This risk has two sides. First, it makes a repeat of the 2011 civil unrest likely in theory, although not in practice as the heightened degree of state repression and widespread climate of fear make it far less likely that people will take to the streets once again in the short-term. Second, and more probable, at a certain point Syria might no longer have resources to divide among the regime’s cronies. This could lead to a different type of conflict, among the country’s elite rather than between the elite and the rest of the population. This, in turn, would accelerate and multiply other negative spill-over effects discussed below.

The politics of refugees

Syrians have become the world’s largest refugee and IDP community. An estimated 6.2 million Syrians are internally displaced within Syria, while an estimated 6 million are refugees in neighbouring countries, mainly Jordan (670,000), Lebanon (1 million) and Turkey (3.6 million).[57]

In Jordan, Syrian refugees constitute 10 per cent of the population, with more than 80 per cent living in urban areas. Only a limited number of these refugees have work permits, meaning that most either work illegally or live in poverty (often both), and rely on humanitarian assistance. In Rukban, in the north east of Jordan along the border with Syria where humanitarian access is limited, 40,000 Syrian refugees are currently stranded. Half of all Syrian refugees in Jordan are children, creating a great need for education services. Humanitarian assistance to Syrian refugees in Jordan is deeply political, since Jordan is struggling with its own economic problems – mainly in the housing sector – which have deepened with the high numbers of refugees in the country. Few Syrians have been returning from Jordan to Syria, citing fear and insecurity among the top reasons.[58]

In Lebanon, Syrian refugees live in the worst conditions in the region. Lebanon is not a signatory to the UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and does not consider Syrian (or, for that matter, Palestinian) refugees as more than guests. Its government sets severely restrictive criteria about where refugees can work and live. In the informal camps, refugees are not allowed to erect permanent structures. This treatment dates back to the complex history of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon. Contrary to its policies towards its Palestinian refugee population, Lebanon has actively worked to send Syrian refugees back across the border regardless of the safety conditions in Syria. According to one analyst, some members of the Lebanese political establishment (especially Sunni representatives close to the Gulf states) are nominally against the repatriation of Syrian refugees – due to the insecurity as well as the fact that refugees bring substantial sums of humanitarian money to the country.[59]

Another section of the Lebanese political establishment seeks to normalise relations with the Syrian regime, which, according to one analyst, itself wants refugees to return ‘to protect the image that the conflict is over and that Syria is a “normal” country’.[60] This is only partially true, however. While the Syrian regime pays some lip service to refugee return and has indeed allowed some Syrians to return into territories under its control, it has also implemented an array of administrative, legal and infrastructural measures that make refugee return more difficult – even dangerous. These include the persecution of conscription evaders, obscure terrorism legislation and selective urban reconstruction efforts – not to mention the general climate of absolutism and fear to which it continues to contribute.[61] Despite concerns over safety, between December 2017 and March 2019, more than 170,000 Syrian refugees returned from Lebanon to Syria.[62]

UNHCR estimates that there are 6.2 million IDPs within Syria, with the pace of displacement remaining high and many people having been displaced multiple times. The situation in the non-government-controlled areas in north-western Syria contributes greatly to this repeated displacement, with more than 300,000 people having been displaced in the region since December 2019.

A great amount of European-funded humanitarian assistance is allocated to supporting IDPs in north-western Syria. Politically, the IDP question is as intricately linked to the regime’s practices, the political economic situation and the other negative externalities as the refugee question. Little can be done to enable a safe and humane return of IDPs to their places of origin, or indeed to prevent their repeated displacement, without having serious leverage over the Syrian regime – leverage that at present the EU does not hold.

In Turkey, the vast majority of Syrian refugees live in urban areas, with less than 3 per cent living in camps.[63] Around one-third of Syrian refugees in Turkey work informally and, as with Jordan, almost half are children, for whom education is paramount. Adult Syrian refugees depend on humanitarian assistance to meet their basic needs. Unlike Jordan and Lebanon, Turkey’s recent military policies are intertwined with its stance towards refugees. Although in general living conditions have been better than in Lebanon, Turkey is the regional host country most involved in directly altering the politico-territorial future of Syria. It has never met the EU’s safe third country criteria,[64] despite agreements around refugees. Its recent military operation in northern Syria is as much about weakening the Kurdish presence in the territory as it is about creating the preconditions for the resettlement of Syrian refugees in the area.[65] Human Rights Watch has denounced Turkey’s forcible return of Syrian refugees, noting that its authorities implement measures such as arbitrary detention in removal centres, forcible signing of voluntary repatriation forms and violence towards refugees who refuse to cooperate.[66] Domestically, this aligns with what seems to be a widespread Turkish desire to see Syrian refugees leave the country, with 85 per cent of respondents to a recent poll of Turkish nationals in favour of refugee return.[67] Various human rights organisations have criticised Turkish authorities for forcibly returning Syrian refugees to Idlib, which is under continued assault by the Syrian regime and Russia, a violation of international law.[68]

The increasing incidence of forcible and voluntary returns, in addition to continuous forcible displacement due to hostilities, is a reminder that the Syrian refugee question is not only a humanitarian but also political matter. Since demographic engineering and sectarianisation have come to characterise the Syrian conflict, refugee and IDP return are processes with significant political consequences. This presents humanitarian actors with a gordian knot: the refugee and IDP question can only be resolved through political action that will, at the same time, exhibit strong preferences in respect of who returns, where to and under what conditions.

The timeline along which a safe and stable environment within Syria can be achieved is long. In the meantime, many Syrian refugees outside the region will have been granted some form of asylum or permanent status. Historically, migrants and refugees granted asylum and who subsequently receive permanent residency or citizenship ‘never return to their country of origin’.[69] Many Syrians who have been granted or have been awarded such status in Western countries are young and educated (often in western academic institutions). It is questionable whether they will be willing to risk everything to return to Syria, be it to mitigate the country’s brain drain or for emotional reasons.

The likely trajectory of voluntary refugee return therefore also depends on what refugees themselves choose, if given the option of return. Several reports have indicated that Syrian refugees in the region are hesitant to return home based on a number of fears, including persecution by the regime for political activities and prosecution for evading military conscription.[70] It is widely believed that the Syrian regime maintains lists of political dissidents and that they know who is not in Syria and who might want to return. One analyst suspected that they have a way of getting information from humanitarian organisations working in Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey. The question of return is therefore contingent upon the Syrian regime’s policies and on refugees’ and IDPs’ perceptions of the regime, not just about their legal status in host countries or even within Syria.

Another geopolitical factor influencing the status of Syrian refugees is Turkey’s leveraging of the refugee question and its military campaigns in Syria. In 2019, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan threatened to ‘open the gates’ of migration to try to put pressure on the EU to support its political-military plans in northern Syria.

Risks and instrumentalisation of terrorism

Terrorism became part of the Syrian conflict almost immediately after the escalation of protests against the regime in late 2011 and early 2012. What began with the regime’s release of several high-profile Islamist prisoners and the ensuing rise of Islamist and jihadist armed opposition groups eventually resulted in a deeply fractured landscape of armed opposition groups battling against one another, and eventually the cataclysmic rise of IS in Syria and Iraq. Terrorism has affected the Syrian conflict in four ways, each of which create different negative externalities for the foreseeable future.

First, it crippled an effective (armed) opposition against the Syrian regime by encouraging internal fighting. This, alongside the Russian military intervention on behalf of the regime, was a key factor in enabling the regime to survive the protests and armed uprising. The infighting among opposition forces escalated to the extent that the original demands of the protestors who took to the streets in early 2011, which were overwhelmingly progressive, were no longer represented by any of the major remaining armed or indeed political opposition groups in Syria itself. As a result, while the EU and its member states should uphold and support the progressive popular demands for change in Syria, there is no realistic armed or political group that embodies these. However, there are Syrian individuals, social initiatives and political platforms that continue to defend and pursue such demands, which should be supported and protected.

Second, the rise of jihadist terrorism in Syria went hand-in-hand with the large-scale presence of external elements among opposition ranks in the form of foreign fighters. More than 40,000 foreign fighters from across the world travelled to Syria to join the ranks of ISIS alone, with around 5,000 estimated to have travelled from Europe.[71] Many of these foreign nationals remain in Syria, either in custody or free. Incidentally, the foreign fighter phenomenon alienated many Syrians from their own struggle and played an enormous role in the erosion of progressive voices among the Syrian opposition. The social discontent embodied by the foreign fighters – in particular those travelling from Europe to Syria – can be read more as an expression of European, Western and global social malaise than as one of Syrian social problems. As an officer of one of Syria’s ISIS prisons exclaimed to the Washington Post, ‘How can the world leave us with this place? All its citizens are here and we are shouldering the burden for all humanity.’[72]

Although many foreign fighters travelled to Syria from the West, many more travelled there from other Middle Eastern and North African countries. It is reported that foreign fighters are attempting to return to unstable or at-risk countries such as Tunisia and Libya, creating a protracted geopolitical risk factor for the EU. As well as increasing regional instability, it confronts Europe with the – legal, social and symbolic – problem of its own foreign fighters and their children.

The third negative impact of terrorism in the Syrian conflict is that it enabled the Syrian regime to ramp up its ‘war on terror’ rhetoric to justify its far-reaching violence against opposition groups and individuals. It frames the Syrian conflict in existential terms that mirror much of the neoconservative rhetoric emerging from the United States in the wake of the wars on Iraq and Afghanistan in the 2000s. In the current phase of the conflict, this remains significant since the regime is now applying domestic counter-terror legislation to opposition activities. Bashar al-Assad recently stated that ‘every terrorist in the areas controlled by the Syrian state will be subject to Syrian law, and Syrian law is clear concerning terrorism. We have courts specialized in terrorism and they will be prosecuted.’[73] This puts individuals who have engaged in any opposition activity – which the regime refers to under the catchall term ‘terrorism’ – at risk of persecution. Additionally, several laws are in place that, combined with the regime’s terrorism rhetoric, put opposition activists at risk of asset seizure.[74] The Syrian regime’s terrorism rhetoric puts Syrians within the country at risk, but also constitutes a significant deterrent for any Syrian refugees considering voluntary return to the country or IDPs considering returning to regime-held areas.

Fourth, the connections between Syria and the West through various ISIS-led or -inspired terrorist attacks in the United States and Europe have dislodged the Syrian conflict from what was initially a domestic conflict and have helped transform it into an international issue. Since terrorism was key in transforming the Syrian conflict’s key issues from primarily domestic to also regional and international, how the negative externalities that emerge in this area are handled by the international community is of great importance. A focus on terrorism solely from an external perspective will increase the risk of a relapse into conflict in Syria, since it will allow for the continued existence of the conditions and organisational infrastructures that helped terrorism groups flourish and expand throughout the conflict.

The risk of an ISIS resurgence is, understandably, a key concern for Western policy makers. Hassan Hassan views Turkey’s incursion into northern Syria as the second lifeline the country has handed to ISIS, since it distracts groups working to secure former ISIS territory in the rest of Syria and draws them to the reopened northern battlefield.[75] In addition, the political instability in Iraq and the potential ramifications of continued US-Iranian tensions are risk factors for an ISIS resurgence. As Crisis Group put it, ‘ISIS is down but not out.’[76] ISIS’s potential resurgence is not only of concern to Western countries. Countless Syrians and Iraqis lost their lives or continue to be marked by the group’s large-scale and brutal violence against them.

Regional instability

The Syrian civil war enabled and accelerated a process of regional power recalibration. Once-dominant states now find themselves either less interested (the US) or decreasingly powerful (Saudi Arabia), while once-minor states are asserting their own foreign policy directions in the region (the UAE). The US experiences greater competition in the region from Russia (politically) and China (economically).

Although the Syrian conflict has had an enormous impact on regional stability in terms of refugee flows, threats of spill-over violence and intra-community tensions, today’s key regional instabilities are as much influencers as they are consequences of the Syrian conflict. These key instabilities are: Iranian influence; Lebanese and Iraqi domestic developments; Hezbollah’s politico-military manoeuvres; Israel’s deterrence strategy; and the rise of the UAE as an assertive regional player.

Realistically, Iranian, Hezbollah and Russian influence in Syria is unlikely to be much reduced in the near future. Simply put, Iran is working to secure its long-term geographical and demographical influence in Syria as a safeguard for its power in the region. As demonstrated in Lebanon and Iraq, Iran plays a long game. Moreover, there has been a degree of regional normalisation with Iran in light of Saudi Arabia’s shifting regional position. For example, as one analyst noted, the UAE had meetings with Iran in the summer of 2019 (for the first time in seven years) about maritime agreements and the possibility of lifting sanctions against Iranians in Dubai.[77]

Regional dynamics have always influenced how Lebanon fares, as all major internal Lebanese issues are intricately linked to the regional power equation. However, potentially Lebanon also has a great deal of impact on Syria, since any unrest there will deeply affect the Syrian economy because of the cross-border economic links between the two countries.[78] These cross-border links are intricately connected to Hezbollah’s political objectives in the region. It has established a strong presence in cross-border smuggling networks. The official border crossings between Syria and Lebanon are used primarily by NGOs, international workers and Lebanese visitors to Syria. One analyst notes how both the Syrian regime and parts of the Lebanese government are trying to make it easier to cross through these official border crossings to promote tourism and normalise relations between the two countries.

In addition, there are a plethora of illegal border crossings that are used for smuggling goods and people – including refugees. Passing through an official border crossing as a refugee can be dangerous because it can lead to detention by Syrian forces. One of the goods smuggled through these routes is marijuana (from eastern Lebanon). Through arrangements with local families and forces, Hezbollah can move large shipments by truck through Syrian towns to reach its main export markets in the Gulf and Syria. There is also a significant weapons smuggling market from Lebanon into Syria. According to one analyst, at many of the illegal border crossings – with help from Syrian armed forces such as the Fourth Division and Airforce Intelligence – Hezbollah facilitates the crossing of people from Syria into Lebanon (allegedly for a fee of US$1,000 per person) and from Lebanon into Syria (to visit family). For the Syrian forces, this is a good source of revenue, which compensates for their poor government salaries. Their participation appears to have the tacit approval of the Syrian regime, presumably since it deems it best to appease its soldiers by allowing them extra income.

Hezbollah uses cross-border smuggling with Syria to cultivate relationships with otherwise politically divergent groups or individuals. Financial rewards are used to build relationships that Hezbollah can, in time, turn into more solid partnerships. One analyst gave examples of such transactional relationship-building occurring across Syria, from Suweida to Dar’a and northern Quneitra near the border with the Golan Heights. Although Hezbollah does not appear to be building direct military capacity here, its presence in Syria as a whole continues to unnerve Israel. While it continues to implement varieties of its historical deterrence doctrine, Hezbollah’s (and Iran’s) widespread presence in Syria makes Israel’s targeted strikes of limited value. Instead, Israel has relied on Russia to safeguard its interests and negotiate a withdrawal of Iranian and Hezbollah forces away from the border areas. However, the trade networks that Hezbollah maintains make for a risk factor that Israel is likely to want to suppress in the short-term. Iran’s and Hezbollah’s military influence in Syria is likely to remain stable or even increase, including their offensive capacities, since pro-regime militias retain an appreciable margin of autonomy from the Syrian armed forces. As a result, Israel is likely to maintain and potentially escalate its deterrence strategy.[79]

Humanitarian culpability

Among the more painfully complex questions in the Syrian conflict has been the role of humanitarian aid efforts in the regime’s divide-and-conquer strategies and, ultimately, its military victory. In particular, the UN-led humanitarian assistance in Syria has been accused of enabling the regime’s deprivation and repression strategies.[80] Millions of dollars in UN assistance were given to close allies of the regime, in some cases organisations led by sanctioned individuals such as Bashar al-Assad’s cousin Rami Makhlouf. Moreover, the UN accepted to work with regime supporters on the ground and even employed them within its agencies, including ‘individuals known for their ties to the Syrian secret police (mukhabarat) and relatives of senior regime incumbents’.[81]

Reinoud Leenders and Kholoud Mansour rightly point to a secondary consequence of this humanitarian culpability, which is that it was a ‘key vehicle by which the Syrian regime has effectively projected and reaffirmed its claims on state sovereignty’.[82] The Syrian regime knowingly used humanitarian assistance to amplify its claims over the country, a process that is likely to recur as the regime attempts to re-establish its legitimacy and authority in the time to come.[83] The Syrian case is not an outlier in this; the regime’s manipulation of humanitarian aid mirrors Darfur and Sri Lanka – only in those cases humanitarian agencies were pushed so far by the incumbent government that they eventually left.

This is all the truer since humanitarian needs in Syria continue to grow. In the north east, just under half a million people, including 90,000 IDPs, require humanitarian assistance and are vulnerable to the military decisions Turkey makes.[84] In regime-held territories, circumstances are equally dire for those who fall beyond the selective remit of regime patronage. There is no question as to whether these needs are deserving of humanitarian assistance. However, transferring insufficiently conditioned humanitarian funds to regime-held areas, or transferring conditioned funds whose conditions cannot be adequately monitored, are likely to be harmful to the EU’s strategic long-term interest in stability in Syria, especially if they directly or indirectly support regime-centred reconstruction efforts. After all, reconstruction and humanitarian or development assistance cannot be artificially separated; they are part of the same equation.

How to properly channel money or assistance sent by the EU is a matter of fierce debate. At the end of the day, the Syrian government has a great deal of control over where the money goes when it comes to its distribution in regime-held areas since, to receive these kinds of funds, organisations have to be registered (and approved) at the Syrian Ministry of Social Affairs. Not all of the organisations registered there are necessarily pro-regime, but it is necessary to keep a low political profile as a registered organisation. There is no way to fully circumvent the regime’s patrimonialism.

Conflict-enabling and -prolonging humanitarian practices were normalised long before the Syrian crisis began, and the desire or pressure to engage in basic relief efforts has frequently undermined durable and positive change. In some cases, such as Palestine, humanitarian assistance even comes to substitute genuine, more controversial political engagement and serves almost as an apology for external actors’ inability to support more meaningful change. The humanitarian culpability in the Syrian crisis is likely to have great repercussions for humanitarian practices elsewhere, since the conflict – and the humanitarian failure – has been one of the most well-documented in recent history.

Deterioration of the international legal order

Previous sections covered the international legal limitations regarding the foreign fighter problematic in Syria. However, preceding these issues has been the overall lack of accountability and the difficulty in achieving prosecution for any war crimes committed by the regime, its allies, and several armed opposition groups and their allies.

This failure has ranged from the systematic violation by pro-regime and regime forces of ceasefire deals to the repeated crossing of ‘red lines’ around the use of chemical weapons by the Syrian regime, neither of which has had meaningful consequences. As a result of years of impunity, the credibility of calls for ceasefires is undermined and the feasibility of establishing an international tribunal has diminished.[85] Additionally, Russia’s diplomatic protection of the regime, as a UN Security Council veto country, makes it unlikely that meaningful prosecution for crimes committed by the Syrian regime and its allies will occur. Selective justice – for example in the form of an ISIS-only tribunal – is a more likely scenario. Although prosecuting those responsible for ISIS violence in Syria and Iraq is desirable, it would be more desirable to do so as part of a conflict-wide effort for justice. Setting the precedent of no justice at all seems only slightly less desirable than pursuing selective justice.