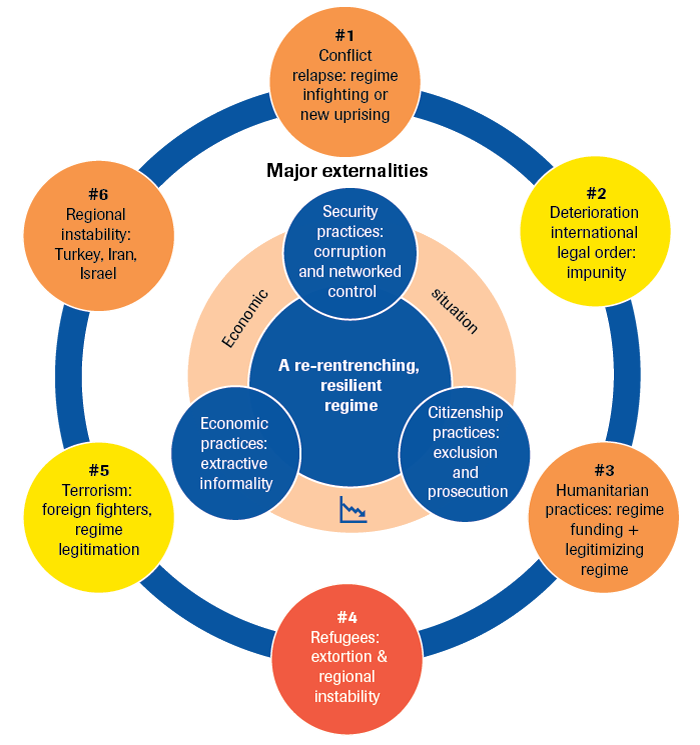

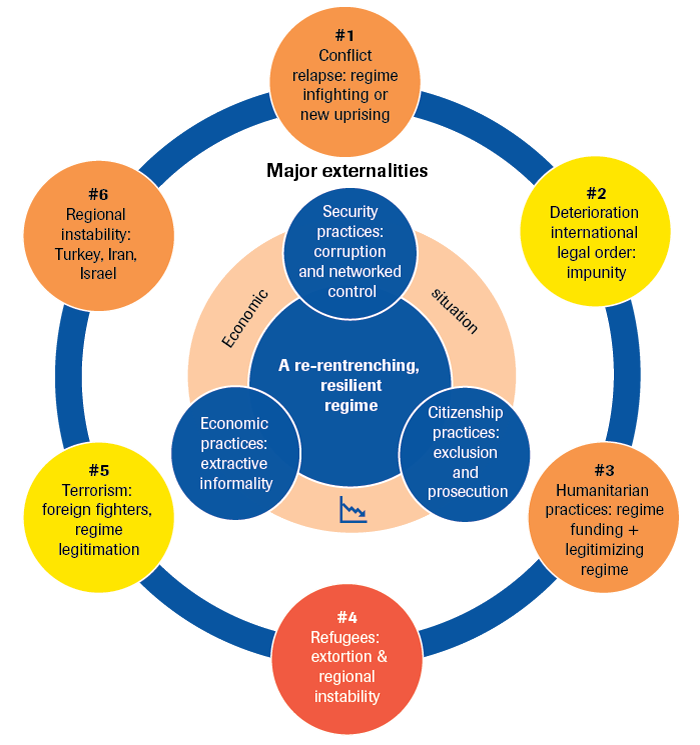

Taking stock of the main findings of this paper, Figure 3 below reflects the nature of the re-entrenching Syrian regime, the deteriorating domestic economic situation it produces, and the negative externalities that ensue. A number of such externalities interact with one another. For example:

‒

Any conflict relapse is likely to turbocharge all other existing negative externalities in the sense of producing more of each of them.

‒

Refugees and regional instability are intimately linked once the refugee situation becomes fully politicised in the domestic and regional politics of the main host countries – Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon.

‒

International impunity, refugees and terrorism are also easily linked once the Assad regime starts using the latter two issues as bargaining chips to thwart any accountability initiatives.

Figure

3

Regime characteristics, economic consequences and negative externalities

Note: The colour coding reflects ‘impact’ x ‘likelihood’ with red representing high risk, high likelihood; orange medium-high risk, medium-high likelihood and; yellow medium risk, medium likelihood (the short-term is weighted more heavily than the long-term).

The one-million-dollar question is how to deal with these negative externalities. Several factors matter here in terms of the possible policy options. These include:

EU policy objectives: EU policy as currently expressed aspires to bring about regime change given its emphasis on ‘a meaningful political transition’. It is unlikely, however, that a regime that just fought – and in the military sense, won – a brutal, nine-year civil war will now open the gates for meaningful political participation and human rights while it remains supported by Russia and Iran, retains strategic control over its armed forces and associated militia, and generates sufficient resources through the illicit and informal economy to satisfy key regime factions and supporters.

The estimated impact of sanctions: The sanctions the EU has imposed on Syria (general and targeted; technically: ‘restrictive measures’) are an echo of their more sweeping US cousins. Both rely on the economic logic of forcing the regime to its knees despite its military victory. While both sets of sanctions undeniably limit the resources available to the regime, they also have side effects that harm the Syrian population. This is particularly true in the case of US sanctions. The problem is that authoritarian regimes – those with no qualms – are able and creative in ensuring their own economic survival while their citizens suffer.

Likelihood of regime concessions / effectiveness of reconstruction support: While concessions that fundamentally change the nature of authoritarian governance in Syria are unlikely to be forthcoming, opinions differ on many other issues. The common denominator appears to be that the regime might be open to mutually beneficial concessions of the same weight (‘win-wins between equals’), if these are framed in language that respects regime sovereignty and authority. For example, European provision of reconstruction support could be exchanged for the local lifting of restrictions such as informal taxes, checkpoint harassment or having to work with partners designated by Damascus – in effect enabling such support to make a positive difference. It is not clear, however, that the ‘concessions’ Damascus might offer are of sufficient interest to European countries to engage on this basis alone.

The growth rate of negative externalities: The real effect of sanctions, path dependencies of wartime destruction and economic mismanagement, revenues from illicit / informal activities, foreign policies of neighbouring states, levels of factional loyalty and levels of foreign support will influence whether the regime will be, in political-economic terms, relatively well off or struggling to get by. In the first scenario it has an incentive to optimise negative externalities to the point where it can still manage them while obtaining a good return from European countries. In the second scenario it has an incentive to maximise negative externalities just to survive.

There are several policy options that can address the factors above while also taking into account the level of EU risk tolerance to negative externalities that will emerge from Syria and affect European cities, borders and people (refugees, extremists, crime and the like). These are discussed in the companion brief of this research report that is more policy focused. This paper concludes by laying out a range of initiatives that could feed into such policy options.

1.

Tighten sanctions? Tightening targeted sanctions against key individuals and organisations that are part of, or linked to, the Syrian regime would aim to deter the regime from playing political games with refugees, terrorism and regional instability, as well as to develop leverage to negotiate measures to reduce such negative externalities in the future. Such a policy would require a significant upfront investment to increase analytical and intelligence capabilities to close the gap between the speed of the sanction-evasive measures undertaken by the regime and the speed with which these are detected. A challenge with this policy option is to ensure that sanction leverage is maintained via a carefully designed and transparently operating mechanism that lifts sanctions in exchange for concessions and can put sanctions back in place just as easily on the basis of regression.

2.

More support for refugees? There will be no large-scale, voluntary refugee return to Syria anytime soon since a re-entrenching regime that places a premium on proven loyalty is not a safe space to return to. As a result, most Syrian refugees in Europe are likely to stay, while refugees in the region will come under increasing pressure from their host countries to leave due to domestic unrest and crisis in those countries. Alternatively, host countries in the region are likely to use the expulsion of refugees towards Europe as leverage in bargaining for funds and other concessions. In short, mitigating the risk of greater refugee movement, regional instability and even criminal/terrorist recruitment requires a more forward-looking refugee policy based on two elements. First, there needs to be greater diplomatic and financial support for the registration and protection of Syrian refugees in Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon focused on their gradual socioeconomic integration into these societies. Second, the EU needs to develop a clearer and more generous policy that welcomes a greater number of Syrian refugees to Europe through a well-thought-out resettlement, education and professional development scheme, with greater support for member states such as Italy and, particularly, Greece.

3.

Increase and improve humanitarian assistance? Given the noted difficulties associated with reconstruction efforts, the continued provision of large-scale humanitarian aid might provide a minimal safety net for the most destitute Syrians over the next decade. However, this is only likely to be effective if the major donors put much greater pressure on the providers of humanitarian aid and the Syrian regime to relax some of the conditions that currently ensure a part of such aid actually benefits the regime. These include, for example, the requirement to work with a (regime-linked) Syrian NGO, submission of plans and provisions to the regime for approval, and regular checkpoints with their associated corruption and appropriation. Success is more likely in the humanitarian than in the reconstruction arena, since the former has less political relevance in terms of the geography of identity, the accumulation of wealth and the social recovery of communities than the latter. Such a policy does require the willingness to reduce or re-channel existing humanitarian aid flows, as well the investment of substantial diplomatic capital for international lobbying and advocacy, especially in the UN system.

4.

Repatriate foreign fighters? Preventing terrorism from emerging as an uncontrolled negative externality in part requires pre-empting it. If and when possible, the relevant authorities should allow imprisoned foreign fighters to return to their place of residence before joining the Syrian civil war. Only this will allow for a measure of controlled return that can be managed from both a criminal and a social perspective. Keeping imprisoned nationals (foreign fighters) in the region will invite further radicalisation, escape, greater grievances and a desire for revenge that is likely to find its way back to countries of origin in some shape or form.

5.

Invest in analytical and intelligence capabilities? Irrespective of the level of pressure on or re-engagement with the Syrian regime – including any humanitarian or reconstruction support – it is likely to produce negative externalities based on its modus operandi, the interests of its foreign sponsors, and the fact that none of the original causes of conflict have been addressed. In short, much greater situational awareness will be required in all cases and this will require investment in long-term research programmes and enhanced intelligence efforts to redevelop an understanding of how the Syrian regime works, how such externalities take shape and how they can be tackled.

6.

Pursue accountability initiatives? In addition to sanctions, another way to increase pressure on the Syrian regime to limit the production of negative externalities is to generously sponsor accountability initiatives. Here, the focus should be incremental, i.e. on prosecuting feasible cases and practical legal steps, rather than waiting for the elusive grand legal process or international court to materialise. Achieving meaningful progress on sub-issues (such as the criminalisation of delivering medical aid to enemies of the regime) can help reverse some of the negative precedents set over the past eight years and articulate boundaries for any form of engagement in regime-held areas. However, to serve as a pressure point, the sponsoring of such accountability initiatives would need to be negotiable, which creates a significant moral dilemma that requires further discussion beyond the scope of this paper.

In addition to the six mitigating policies outlined above, the fluidity of the Syrian civil war, regime re-entrenchment and the certainty of negative externalities make it advisable to design a structured and regular form of scenario planning to underpin and recalibrate policy development. This can be done inhouse within European foreign affairs ministries, outsourced, or in hybrid form. It could easily be connected with policy option (5) ‘invest in analytical and intelligence capabilities’ and can help ensure that policies stay as close to Syrian and regional realities as possible, instead of remaining stuck in moral positions or unrealistic expectations.

What will be inevitable in almost any policy scenario is the re-establishment of some form of communication with the Assad regime. Not because of any belief in its civility or potential for redemption, but simply because it runs the Syrian state in a world organised on the basis of state sovereignty and international relations between states. Such communication can take many forms, ranging from envoys based in Beirut or Amman, re-opening embassies, or collectively working through an EU representative office. What is appropriate will depend on national and EU policy lines and the price the Assad regime tries to extract. Care must be taken to avoid bolstering the legitimacy of the Syrian regime. In other words, there is a need for a parallel public diplomacy effort underlining that such communication is based on the legality of the Syrian regime under international law, but does not signify either agreement with its policies and practices, or that it views it as the legitimate representative of the Syrian people. However, after eight years of war and atrocities, words will not be sufficiently convincing. Firm parallel policies will need to be pursued to make such statements convincing, for example via the pursuit of meaningful accountability initiatives.