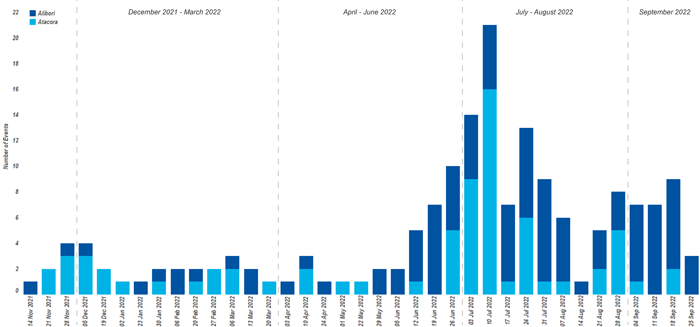

During 2020 and 2021, the presence of VEOs in Benin was largely of a transitory nature. Since the first attack on Porga in November 2021, however, the violence used by these groups has expanded and Benin has become a new battlefront. VEOs now seek to control populations and territory. We can discern four phases.

Source: ACLED, Supplemental data (supplemental data added from June 2022 onwards)

December 2021-March 2022; The ‘Maginot Line’

Following the Porga attack, in the period from December 2021 to March 2022, Benin faced several incidents linked to VEOs. These activities were mostly concentrated in Atacora where the Parks, rather than populated areas, were targeted. Most of the violent episodes were linked to one group – Katibat Mouslimou – a Jamāʿat nuṣrat al-islām wal-muslimīn (JNIM) subgroup formed in Burkina Faso.

Benin’s response was the creation of a protection force along the border – a symbolic ‘Maginot Line’ (the French defence line against Nazi Germany). The Force Armée Béninoise (FAB) sought to control the entire border with Burkina Faso through a set of (mobile) border posts and bases in the Pendjari and Park W and a subsequent no-man’s land perimeter between Burkina Faso and Benin – to keep VEOs at bay. The idea was to prevent VEOs from pushing through and gaining footholds in Benin.

April – June 2022: An emerging security vacuum

By April 2022 the ‘Maginot Line’ had proved to be untenable. Around this time, the Monsey Police Station was attacked which created serious concerns for the Benin security system. The fear was that JNIM had expanded its battlefront.

Indeed, the defence mechanism started to crumble. This first emerged through IEDs. Various IEDs were planted in the Parks and around defence outposts. This greatly jeopardized the defence as intelligence supporters – such as the African Parks Network (APN) – and FAB staff became unwilling and reluctant to operate in the area. At the same time, in armed clashes JNIM tended to come out on top partly as it had better weapons.

For some time, FAB considered a revision of its strategy towards counter-guerrilla tactics and better protection against small-scale ambushes (e.g. through armoured vehicles). Yet, before this materialized, it became increasingly clear that ambushes, IEDs and direct armed confrontations decreased the willingness of Benin security officials to fight. Many feared that they were outnumbered, less well equipped than their opponents and were therefore vulnerable to attacks.

As morale diminished, the defence of the Parks declined. The FAB withdrew from border posts and retreated to the areas around Park W (with the caveat that their presence in Pendjari was somewhat maintained). Consequently, VEOs were presented with an unprecedented opportunity and freedom to move into Benin. This change in defences allowed them to freely move across the Parks within 2 to 4 hours and to access surrounding villages to collect supplies and interact with the population.

July-August 2022: Control of the Parks and their surroundings

This resulting security vacuum has turned the tide for Benin. Since July, VEO groups have increased their attacks and gained a foothold in the country. The months of July and August saw many encounters and armed clashes with FAB around the Pendjari National Park (Atacora) and later Park W (Alibori) such as Guene (Alibori) and Monsey (Alibori). Large parts of the Parks fell under the de facto control of VEOs as they moved more freely around the Parks.

In these areas (e.g. Koualou, Dassari, Materi (Atacora); Goungoun, Guene, Karimama, Monsey, Pekinga (Alibori)) local populations find themselves under a constant threat from VEOs. They face voluntary and forced conscription, they partly depend on VEO permission to carry out subsistence activities and are subjected to preaching. In these areas, it has become taboo to discuss VEOs. Criticising these groups and/or showing any support for the army has serious consequences and often means that such people are targeted and, in some cases, killed.

September 2022: the entry of ISGS and a strategic pause?

The beginning of September, however, has seen another key change: the announcement of the presence of ISGS in Guene, Boiffo and Malanville (Alibori). Revealed at the onset of the rainy season and accompanied by deliberate provocation, this move demonstrates that ISGS appears to showcase, if not expand, its presence, authority and capacity in this Department.

While it is still ongoing, the presence of ISGS could be a game-changer for Benin. It is already evident that Alibori has surpassed Atacora as the most active conflict zone.[3] Such dynamics risk inflaming conflict, however, particularly if JNIM and ISGS start to actively compete over the same territory.