Moldovan domestic politics have a long tradition of both instability and susceptibility to Russian influence for a variety of reasons. This chapter explores four vulnerabilities that contribute to Russia’s leverage over Moldova’s national politics: the long-standing but evolving divisions within Moldovan politics over geopolitics and identity; dependency on Russian gas; the specific situation of national minorities; and Russia’s considerable media influence inside Moldova. Most of these vulnerabilities predate the war in Ukraine and sometimes have roots that go back decades. That said, they influence significantly how society and politicians have responded to the war.

Traditional and evolving political divisions over geopolitics and identity

Moldova’s complex history of being part of – and suffering at the hands of – various powers is traditionally reflected in the political views and geopolitical preferences of its electorate. In particular, the turbulent 20th century saw the region, then known as Bessarabia, taken from the crumbling Russian Empire in 1918 and incorporated into Greater Romania, only to be carved up by Stalin and Hitler two decades later by the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in 1939. During World War 2 the Soviet Union and Nazi-allied Romania fought bitterly over Moldova, which was eventually annexed by the Soviet Union. This left deep scars in different sections of Moldovan society. These diverging historical memories between groups that are sometimes described as ‘Moldovenists’ and ‘Romanianists’ still influence Moldovans’ political perceptions of Russia and Romania, as well as their attitude towards the Russian and Romanian languages.[4]

For nearly 20 years after Moldova’s independence in 1991, politicians actively used these sentiments and divisions to mobilise their respective electorates against one another and to secure support from Moscow, Brussels, Washington or Bucharest – and often used them to obfuscate internal problems such as poor governance, persistent corruption and lacklustre economic reforms.[5] What is known in Moldova as the ‘left’, originally represented primarily by the Communist Party (PCRM) of Vladimir Voronin and later by the Socialist Party (PSRM) of PCRM defector Igor Dodon, traditionally promotes good relations with Russia, a stronger position for the Russian language, Moldova’s distinctiveness from Romania and a sympathetic approach towards Soviet history.[6] The left is openly supported not only by the Kremlin but also by the Moldovan Orthodox Church, which is canonically subordinated to the Russian Orthodox Church and which espouses socially conservative values and sometimes takes a political position.[7] After a first turbulent decade, this faction was in power from 2001-2009 under Vladimir Voronin, and from 2016 made a comeback under Igor Dodon, who won the Presidential election in 2016 but failed to secure a strong parliamentary majority.

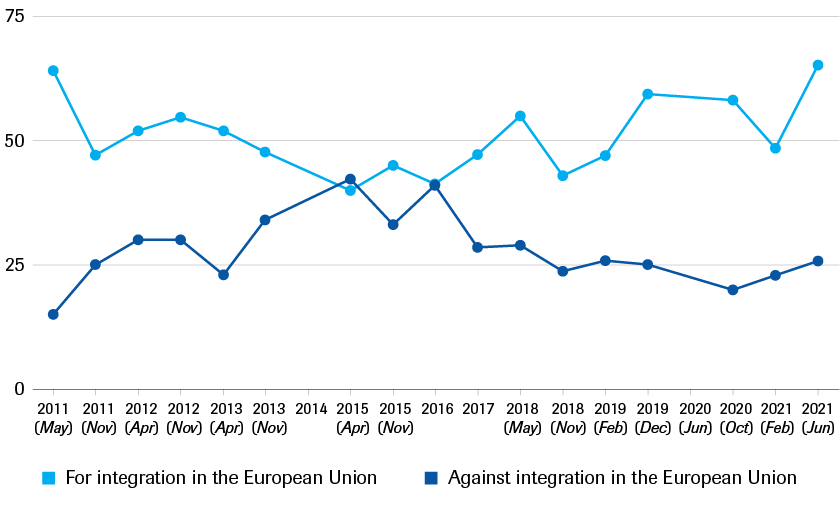

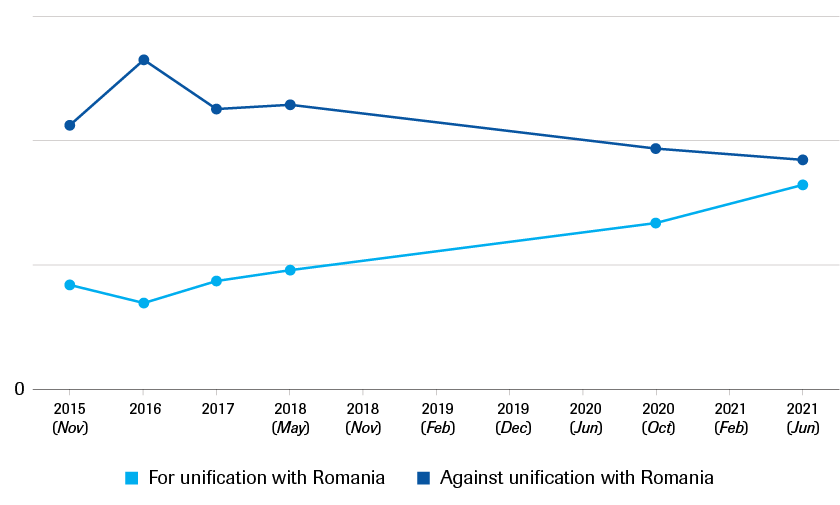

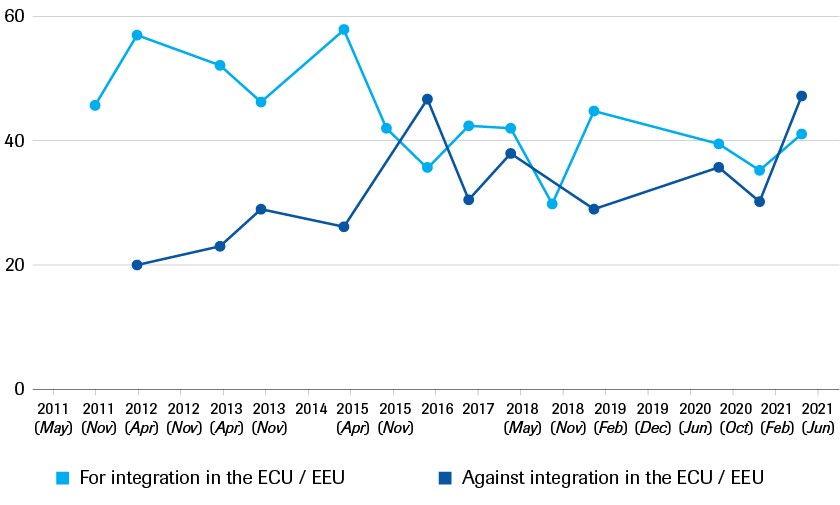

The ‘right’ in Moldovan politics pushes for a stronger Romanian identity, less dependency on Russia and a more westward geopolitical orientation towards the European Union or – to a lesser extent – even unification with Romania. In the period 2009-2019 various unstable parliamentary coalitions, predominantly headed by centrist and right-wing parties, many of whom had close links to Moldovan oligarchs, pursued a nominally pro-European and pro-Romanian course. Although they initially secured strong support from the EU, and from Romania in particular, in reality the ‘Alliance for European Integration’ and its successors embarked on a process of largescale enrichment and a ‘takeover’ of government institutions and the judiciary. This process was spearheaded by the Democratic Party (PDM), the political vehicle of oligarch Vladimir Plahotniuc, who gradually eliminated most of his oligarchic rivals including Veaceslav Platon and Vladimir Filat.[8] Ironically, this initially led to receding support for European integration in the period 2011-2015, although the overall trend is consistently towards a more pro-European course and decreasing support for membership in the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union (EEU). In turn, unificationist sentiment is gradually increasing but still has more opponents than proponents – and for many Moldovans unification remains an ideal, but not a realistic proposition (see Figures 1-3).[9] [10]

Source: Institute for Public Policy (IPP), “Barometer of Public Opinion”, 2011-2021, retrieved July 2022.

Source: Institute for Public Policy (IPP), “Barometer of Public Opinion”, 2011-2021, retrieved July 2022.

Source: Institute for Public Policy (IPP), “Barometer of Public Opinion”, 2011-2021, retrieved July 2022.

In this regard, it is a frequently held misunderstanding that Moldovan political parties are simply ‘pro-European’, ‘pro-unification’ or ‘pro-Russian’. In fact, most are opportunistic and personality-driven patronage networks that pragmatically try to balance relations with all ‘sides’ to advance their own interests. For example, for all his catering to nostalgia towards the Soviet Union, Communist party leader Voronin signed numerous agreements with the European Union and in 2008 even declared Moldova’s EU integration process an ‘irreversible process’.[11] Despite frequent statements of support for Russia and the Eurasian Economic Union, in which the PSRM negotiated an observer status in 2017, Igor Dodon did not suspend this integration process either. In turn, the period in which various pro-European parties were in power was marred by three factors: political instability, lagging reforms and largescale corruption. The latter was epitomised by the ‘bank heist of the century’ in which approximately 1 billion USD were embezzled and the banks involved had to be bailed out with public finances from an impoverished Moldova. After a constitutional crisis in 2019, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe went as far as to use the term ‘state capture’ to describe the situation of democratic and judicial institutions in Moldova.[12]

In response, exasperated Moldovan voters increasingly turned their backs on the old political divisions running along geopolitical and identity lines and turned towards a new political movement running on an anti-corruption platform, the Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS) of Maia Sandu.[13] While promoting a pro-European geopolitical orientation, Sandu largely steered clear of identity issues such as language policy. In 2020 she defeated Igor Dodon in the presidential election and in 2021 secured a parliamentary majority for her party. This not only signified a strong preference for Moldovan voters to do away with corrupt practices of the past, but also indicated that geopolitical and identity factors had lost importance and that ‘most of the citizens no longer allowed themselves to be trapped by scarecrows and sterile geopolitical discourse’.[14] The fact that a party running on an anti-corruption agenda secured a strong parliamentary majority is in principle a positive development. However, several interviewees expressed concern that the combination of PAS appointees’ lack of experience, high levels of distrust both inside the party and towards all other political forces, and a strong drive to ‘quickly clean up’ democratic institutions could have longer-term negative effects for the independence of these institutions, as well as for political pluralism and democratic consolidation in Moldova.[15]

The electoral victory of PAS was also facilitated by a shift in labour migration, geopolitical orientation and the voting patterns of the sizable Moldovan diaspora away from Russia and towards the EU. In 2021, those ‘external voters’ made up 18.2% of Moldova’s electorate and a whopping 86.2% of them voted for PAS, against only 2.5% for the Electoral Bloc of Communists and Socialists (BECS).[16]

This shift also meant that Moscow had to adjust its strategy. In the past the Kremlin was able to influence the outcomes in Moldovan elections through its media presence and by showing overt support for the leaders of the Communist or Socialist parties. But due to the plummeting popularity of both of these parties Moscow had to diversify its approach and the ‘Russia factor’ in Moldovan politics has become more amorphous. In particular, the Kremlin had to look for an alternative to Igor Dodon. Most tellingly, when Dodon was arrested in May 2022 on charges of corruption and treason, Russia did not come staunchly to the defence of its traditional ally but instead declared this an ‘internal affair’ that it would ‘monitor’.[17] The Kremlin is now cultivating stronger ties with several political actors and new political forces beyond the PSRM and PCRM, including Chișinău mayor Ion Ceban, former prime minister Ion Chicu and various politicians in Gagauzia. Most worryingly, there is a risk of collusion between the interests of Russia to keep Moldova out of the EU’s geopolitical orbit and those of various political and oligarchic factions in Moldova whose positions are threatened by the anti-corruption reforms of PAS, including those of Vladimir Plahotniuc, Veaceslav Platon and Ilan Shor.

For now, it appears that the Kremlin – which has its hands full in neighbouring Ukraine – is content to bide its time in Moldova and see which political force ‘floats to the top’.[18] Instead of actively trying to topple the Gavrilița government, Moscow has several other levers it can use to pressure Moldova and avoid it taking a pro-Ukrainian stance too openly in the war or deviating from its formal neutrality – including through alignment with EU sanctions. This is first and foremost through its control over Moldova’s energy supply and the concomitant effects on Moldova’s economy and social stability, which may be more effective for Russia to achieve its political objectives than direct meddling in Moldovan domestic politics.

Winter is coming again: Moldova’s gas debt and dependency on Russian energy

Moldova is almost entirely dependent on the Russian Federation for its supply of natural gas and, indirectly, for a large proportion of its electricity supply. MoldovaGaz – 50% of which is owned by Gazprom and 13.4% by the de facto Transnistrian administration – imports approximately 2.9 billion cubic metres (bcm) of natural gas. Out of these, 1.3bcm is consumed by right-bank Moldova for heating purposes and 1.6bcm is consumed on the left bank of the Dniester by Transnistrian heavy industry and the ‘Moldavskaya GRES’ power station (MGRES) power plant in Kuchurgan, which provides around 70% of the electricity for right-bank Moldova as well. Over the years Transnistria has racked up an astronomical debt of 7 billion USD, but right-bank Moldova also owes Gazprom around 700 million USD.[19] Chișinău in effect has to pay Moscow twice: first for the import of the gas to Transnistria, and then to MGRES to import the electricity from Transnistria – albeit at prices that are substantially lower than on the international electricity market.

This double reliance on Russian gas and Transnistrian electricity, combined with the sizable debt to Gazprom, gives Russia a strong grip on any Moldovan government. Gazprom could at any time use the debt as a pretext to suspend gas deliveries to Moldova, although it would also deprive its ‘allies’ in Transnistria of electricity and heating in the process. Knowing this, the Moldovan government similarly does not always implement all of its contractual obligations towards Gazprom. When Moldova missed the contractual deadline for an external audit of its debt to Gazprom, the company nonetheless continued to supply gas to Moldova, and MGRES continued to supply electricity at subsidised rates – reportedly in exchange for an environmental licence for the scrap metal processing plant in Rîbnița that plays an important role in the Transnistrian economy.[20] Russia-related energy imports are therefore not only a key source of potential kleptocratic enrichment on both banks of the Nistru and in Russia, they are also a critical vulnerability that the Russian Federation can and does exploit.

In fact, Moscow did not wait long after the PAS victory in the parliamentary elections to test Maia Sandu and her new government. In October 2021, when Moldova’s previous long-term contract with Gazprom expired and gas prices had shot up, Russia began to charge Moldova the full market price of 790 USD per million cubic metres (mcm), up from an average of 148 USD/mcm in 2020. Partially due to its own procrastination and inability to anticipate the ending of the contract, the Moldovan government had to issue a state of emergency and scrambled to source gas from alternative suppliers. It eventually made a new, temporary deal with Gazprom that indexed the gas price to a rolling average over the preceding months and temporarily cushioned the blow to Moldova. However, this only postponed the problem, as gas prices kept rising further and further. While Sandu denied that she had made any political concessions, Gazprom had reportedly pushed for a weakening in trade ties with the EU, including in the implementation of the Third Energy Package. Some ambiguous wording about this made it into the protocol, but the exact concessions made by the Moldovan authorities to Gazprom remain unclear and a new spat is possible virtually at any time.[21]

Pending more sustainable solutions regarding the debt restructuring to Gazprom, the electricity supply from Transnistria and a broader solution to Russia’s grip on the wider European gas market, Moldova will remain acutely vulnerable to disruptions or sharp price increases in its energy supply. Fears abound that higher heating bills this winter will combine with simmering social discontent and mobilise the electorate against the Gavrilița government, leading to social and political instability and a possible change of power.[22]

National minorities and the position of the Russian language

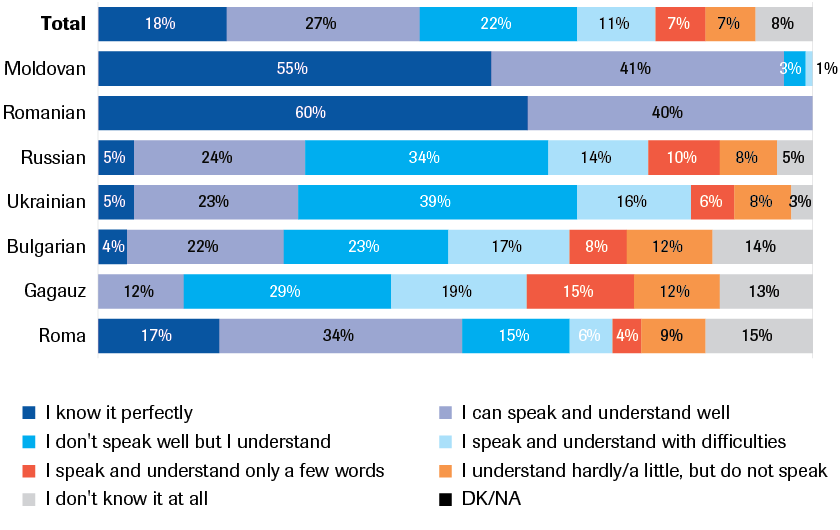

When Russian general Rustam Minnekayev made his ominous but rather ill-founded threat in April 2022 to take the entire south of Ukraine ‘as a way out for Transnistria’, he also referred to ‘facts of oppression of Russian-speakers’, prompting fears that Russia might want to use the status of the Russian language as a pretext for an operation against Moldova itself.[23] Foreign Minister Lavrov echoed these statements in a recent TV interview, in which he said Russia would defend Russian-speakers in Moldova and also mentioned Gagauzia.[24] Issues of language and ethnicity are highly sensitive issues in Moldova for the historical reasons explained above.[25] In addition to divisions within the majority population (which is largely bilingual, but has different linguistic preferences for the use of Romanian or Russian), the country is also home to several sizable national minority groups. Roughly 18% of right-bank Moldova identified as a minority in the 2014 census, of which ethnic Ukrainians (6.6% of the total population), Gagauz (4.6%), Russians (4.1%) and Bulgarians (1.9%) comprised the four largest groups. Many live compactly in regions in the north and south of the country, have limited knowledge of Romanian and generally speak Russian as their preferred language of everyday use. They also consume significantly more Russian-language media, including content produced in Russia, compared to the majority population.[26]

The status of the Russian language in Moldova has been an issue of political and legal controversy since independence. In its 1989 language law Moldova recognised Russian as the ‘language of inter-ethnic communication’ alongside the state language. It nominally remained in force until the Constitutional Court annulled it in 2018.[27] Attempts to pass a new language law or adopt a balanced language policy that does justice to Moldova’s complex linguistic legacy have failed for many years due to fierce mobilisation along ethnic and linguistic lines and a tendency by political actors to abuse this issue purely for short-term political gain. For example, in January 2021, Igor Dodon made use of his temporary majority in the Moldovan parliament to pass a law on the official status of the Russian language that was promptly thrown out by the Constitutional Court. Successive governments and parliaments have dragged their feet for 20 years and still have not ratified the European Charter for Regional and Minority Languages (ECRML), even though Moldova signed it in 2002 and promised to ratify it as part of its pre-accession criteria towards the Council of Europe.[28] While language policy remains deadlocked, the issue continues to fester and might be used at any time by domestic political actors or the Russian Federation to stir up controversy – not only within the majority population, but in particular towards national minorities.

Source: CIVIS Centre, Ethnobarometer Moldova, 2020.

Typically, people belonging to national minorities are staunchly opposed to the idea of reunification with Romania and generally tend to vote for parties on the left of the political spectrum that advocate for a stronger position for the Russian language and closer ties with Russia. It is nonetheless a frequently held misunderstanding that minorities in Moldova are all ‘pro-Russian’ or ‘anti-European’; most support the general idea of European integration and concomitant reforms such as the fight against corruption, but are more susceptible to narratives in Russian-language media that emphasise socially conservative values and resistance against ‘Gayropa’.[29] Since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine they have tended to emphasise Moldova’s neutrality more than voicing staunch support for Russia’s invasion.

Minorities are also – with good reason – concerned that they have been insufficiently involved in political life by the parties of the right and are under-represented in various state structures.[30] As national minorities traditionally vote predominantly for PCRM or PSRM, other parties such as Maia Sandu’s PAS pay relatively little attention to their concerns. It is telling in this regard that the government is yet to appoint a new director for the Agency for Inter-ethnic Relations. This agency is key in the implementation of the ‘Strategy on Consolidation of Inter-ethnic Relations’, adopted in 2016 with support of the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) High Commissioner on National Minorities (HCNM). Implementation of this strategy has been slow and there is a lack of genuine efforts to promote integration of Moldovan society, including through better knowledge of the Romanian language by persons belonging to national minorities and by promoting their participation in public life. This, combined with the inability of successive governments to strike a reasonable compromise regarding the status of the Russian language, continues to present opportunities for domestic and external political actors to manipulate sentiments over language and identity. While many national minorities and Russian-speakers, disillusioned by previous governments and frustrated by pervasive corruption, voted for PAS in the 2021 elections and helped Sandu obtain a parliamentary majority, they may not do so in the future if they feel the party advances only the aims of the Romanianist majority.[31] PAS officials sometimes speak about the importance of building an overarching civic Moldovan identity which would contribute to a more inclusive and cohesive Moldovan society, but have so far taken limited steps in this direction.

‘Don’t mention the war’: Russian media content and narratives

The linguistic divisions in Moldovan society contribute to the emergence of parallel realities for those who consume Romanian-language or Russian-language media. While this also applies to print and online media, it is particularly television, the most popular source of information for almost three-quarters of the population, that is of critical importance in shaping attitudes towards key (geo)political issues.[32] This also extends to the war in Ukraine, which divides Moldova in general but also sees a correlation with linguistic preferences and media consumption. For example, in a survey in May 2022, 51% of those whose native language is Romanian considered Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as aggression, compared to only 20% of those who speak Russian or other languages. While there is no clear-cut causal link between native language and perceptions, given that nearly half of Romanian speakers view the war differently, the correlation is nonetheless strong.[33]

Due to the popularity of re-broadcast content from Russia, Moldova has long been highly vulnerable not only to Russian narratives, but also to disinformation campaigns. Together with Belarus it ranks as the country in Eastern Europe least able to withstand foreign-led information threats in the Disinformation Resilience Index.[34] As Moldova’s domestic market is relatively small, it is difficult for Moldova to produce Russian-language entertainment content that can rival the quality of content re-broadcast from the Russian Federation. An additional complication is posed by long-standing problems regarding media ownership and pluralism. For years, political and oligarchic actors in Moldova have used media holdings to pass their own, politically biased messages through their respective TV channels.[35] They often make use of Russian-produced content to increase their popularity and have business links with Russian media moguls connected to the Kremlin. For example, content produced by Russian state TV channels Perviy Kanal and RTR have consistently been among the most popular in Moldova. Such content was first re-broadcast by Plahotniuc-controlled PRIME TV, but later taken over by a channel of a media holding that is close to the PSRM, Media Invest Service, which owns Accent TV and Primul. Media Invest Service is 51% owned by Igor Chaika, the son of Russia’s prosecutor-general.[36]

The Moldovan government has tried to take action. In its 2018 National Information Security Strategy it acknowledged that disinformation campaigns are part of hybrid warfare and can create internal instability.[37] In the same year the PDM-led government banned news and analytical broadcasts and limited other content from non-EU countries that had not ratified the European Convention on Transfrontier Television (ECTT), which was a roundabout way of saying ‘the Russian Federation’ – especially as exceptions were made for the United States and other countries that had not ratified the Convention. Although the coalition circumvented a presidential veto by Dodon, the ban was widely perceived as political manipulation by Plahotniuc. It also did not prove to be particularly effective, as media consumption moved more online, cable operators in Gagauzia refused to implement it and the PSRM bitterly fought it in the parliament.[38] The Audiovisual Council, the key institution mandated to regulate the media sphere, remained unwilling or unable to address the problems of media ownership and the risk of Russian disinformation.

However, it was the war in Ukraine that again noted the urgency of information space as a security issue and prompted action, as Moldovan authorities became acutely concerned about the risk of Russian propaganda spreading throughout the country. The Moldovan security services quickly shut down Sputnik on 26 February on the grounds that it ‘promotes information that incites hatred and war’. But rather than outright pro-war propaganda, it is manipulation of public opinion through omission or the repetition of Russian narratives about discrimination of Russian-speakers that have a more pernicious and divisive effect on public opinion.[39]

In June 2022, parliament passed a new Law on Information Security that once again banned news and analytical programmes and imposed a cap on other content from non-ECTT signatory countries. The ban was again criticised harshly by Moscow and PSRM deputies.[40] Its effectiveness remains to be seen, as media consumption increasingly moves online and is hard to regulate. Russia’s presence in Moldova’s information space remains a key vulnerability that can only be addressed by a complex set of measures, ranging from promoting media literacy to producing more local Russian-language news, and from addressing media ownership to strengthening governmental and civil society responses to fake news.