The triggers

Several factors related to state control over media can be identified as having an impact on the quality of media content offered to citizens. This section analyses the issues of media ownership and privatisation, the economic unsustainability of the media and the accompanying state funding issue.

A long-standing media ownership problem is one of the factors of partial reporting. Due to the flawed media privatisation process that started in the early 2000s, the state co-owns two dailies (Večernje novosti and Politika) and the news agency Tanjug, in addition to the public broadcasting service. Considering that these print media also have their online portals, the state appears to be the only media owner actively operating in all four media sectors in the country (TV, radio, print and online).[33] When it comes to the national TV broadcasters (public and private), alternative reports state that the government and people linked to it have full control over them,[34] holding a 63.33% share of the total TV audience.[35] Plurality of thought offered to Serbian citizens is thus questionable. With such a wide reach, the government can easily impose the messages it seeks to spread across the country. This leads to covers, in this case of Večernje Novosti, with headlines like “Half of the world is bleeding due to America's greed” or “No one will get us into a fight with Russia”.[36]

Another problem in Serbia is that with over 2,000 registered media on the one hand[37] and the insufficient media market value on the other,[38] outlets are increasingly vulnerable to state funding. Forms of transactions range from public calls to the co-financing of media projects and from public procurement of media services to direct advertising contracts etc. Such financial dependence leaves room for the authorities to apply latent pressure on editors. For example, journalists report that funds for co-financing media projects of public interest have been awarded in a non-transparent way, often to pro-regime and tabloid media that are known for breaking the journalists’ code.[39]

The media ownership problem, combined with the fragile economic sustainability of media outlets, makes the mainstream journalistic profession in Serbia susceptible to government bias. As stated by an interviewed journalist, the “wage for fear” is too small for many media workers, making them lose motivation to fight for freedom of information and their own personal freedom.[40]

The contributors

A number of other issues related to the overall media landscape in Serbia add to the environment in which impartial reporting comes at a high price for the stability and security of journalists’ jobs. This section analyses just some of the outstanding issues: threats, pressure and violence towards journalists; the impunity phenomenon; and tax audit abuse. By setting an unfavourable context for the conduct of journalism in the country, these problems indirectly contribute to the spread of media bias.

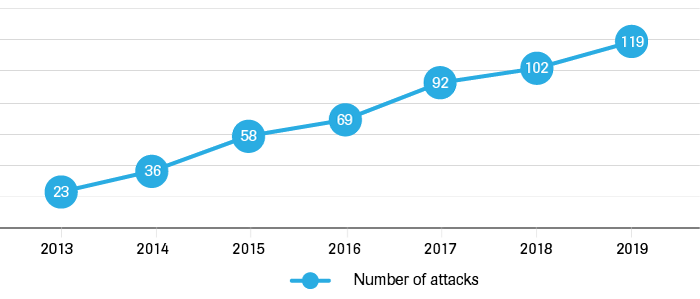

Threats, attacks and intimidation of journalists and other media workers are continuous. According to the Independent Journalists’ Association of Serbia, the number of attacks (including physical attacks, attacks on property, verbal threats and pressure) is increasing, with a recent severe case of an investigative journalist’s home being broken into in October 2019.[41] Pro-regime media engage in smear cases and verbal attacks, but legal remedies are limited.[42]

Source: Independent Journalists’ Association of Serbia, database of attacks on journalists by year

Digital threats to independent journalism are equally worrying. One monitor showed that journalists are the most frequent targets of violations of digital rights and freedoms in Serbia.[43] The European Commission has therefore called upon the Serbian authorities to make serious efforts to identify and prosecute “those suspected of violating internet freedoms, as well as those using social media to intimidate and threaten journalists”.[44] Verbal harassment by online accounts is very often gender-based, which has compelled the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network to start tracking stories of female journalists who faced online violence.[45] Additionally, some members of the current government have publicly cited the names of particular journalists in press statements, making them direct targets for online hate speech. Interviewed journalists stated that this practice was very unpleasant and at times frightening to them.[46] Larger independent media outlets have fundraising and legal capacities to invest in protection software, but the problem lies with small, local media, which usually struggle to afford expensive cybersecurity experts or technical solutions. These examples show not only the growing problem of digital security impeding professional journalism, but also the multidimensional nature of the costs of pursuing a journalistic career in Serbia.

The government is suing us. It makes us pay seemingly random tax bills. It follows us with intelligence agents and publishes fake stories in pro-government media about us. It even created a fake network of investigative reporters who only seem to investigate us and other so-called enemies of the state. KRIK (Crime and Corruption Reporting Network) team members are under court proceedings now. Threats have been sent to our newsroom. And the homes of two of our reporters were broken into and we have been targets of surveillance by the secret service for a long time. They published lies about me on the front pages of Serbian leading media. It feels like it was never as hard as today to tell the truth.

Source: Stevan Dojčinović, KRIK (Crime and Corruption Reporting Network), source: AJ+ link

Even when journalists report violence, most cases end up without investigations and convictions. There is systematic negligence of this problem, reflected in the lack of political will and low institutional capacities to deal with the problem. In many cases, investigative journalists, i.e. the victims, are the ones doing the data collection for the prosecution authorities, but the process ends without any action taken.[47] Journalists believe that causes of impunity lie in the political influence over public authorities and links between authorities and protected crime groups.[48] In this sense, punishment for perpetrators is important but does not solve the systemic problem. Knowing that culprits are rarely brought to justice, journalists feel discouraged from reporting new harassments and attacks.

We spent hours with the police submitting evidence to help the investigation, but we never received any meaningful information years later.

An interviewed journalist

The sustainability of independent media is further harmed by administrative-institutional pressure, such as tax authority abuse. Daily visits from tax inspectors to media outlets can last for weeks, completely occupying the newsrooms and preventing employees from performing their jobs. This happened in 2017 to the local weekly Vranjske, which soon after closed the business despite a large protest by the media community, because they could no longer withstand the pressure.[49]

The novel coronavirus crisis has revived the discussion in society, but primarily within the government, on what constitutes information as against disinformation. The government issued a decision (which was withdrawn shortly afterwards) banning the dissemination of information on COVID-19 in Serbia by sources other than the core government crisis response team, headed by the Prime Minister. Expert observers considered that this centralisation of information represented a drastic violation of freedom of expression, freedom of the media and the right to be informed.[50] Furthermore, a journalist was held in 48-hour police detention for allegedly spreading panic due to an article on the lack of medical equipment and unprotected medical staff in one of Serbia’s hospitals.[51] Serbian CSOs asserted that “such treatment of journalists not only represents a violation of media freedom, but creates an intimidating effect for all journalists in Serbia”.[52] These examples additionally showcase the vulnerability of the media in the extraordinary circumstances.

All the issues mentioned lead to censorship and self-censorship in the mainstream media in Serbia. Interviewed journalists confirmed this unanimously. Journalists resort massively to softening their tone and approach, making compromises for the sake of their personal and professional sustainability. This points to a link between the severe condition of the journalistic profession today and the quality of reporting. It therefore comes as no surprise that reporting, including on foreign actors, becomes poor and biased.