Acknowledging the need for increased cooperation between the EU and NATO is not something new but has gained momentum in recent years. This is particularly true since the EU and NATO are redefining their roles in light of changing security challenges. The EU’s Joint Communication on Countering Hybrid Threats from April 2016 and the EU Global Strategy of June 2016 already emphasised the need for a strengthened partnership with NATO.

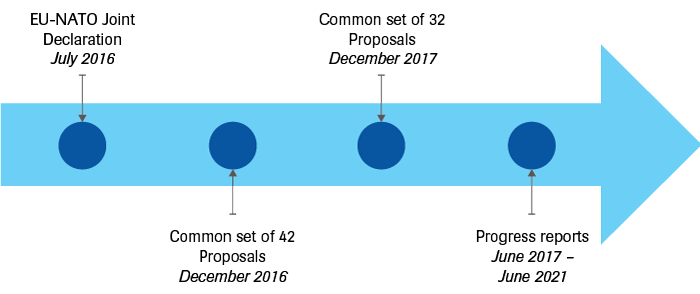

Eventually, this need for further cooperation led to the adoption of the EU-NATO Joint Declaration at the NATO Summit in Warsaw in July 2016. This declaration identified seven areas of cooperation: countering hybrid threats; broadening and adapting operational cooperation; expanding coordination on cyber security and defence; developing coherent, complementary and interoperable defence capabilities; facilitating a stronger defence industry; stepping up coordination on exercises; and building defence and security capacity and fostering the resilience of partners.[14]

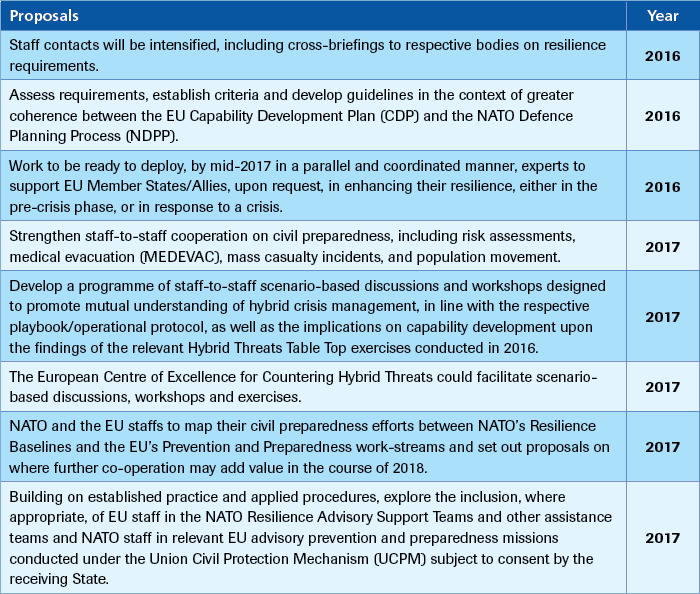

Following the adoption of the declaration in 2016, the EU and NATO drafted the 2016 and 2017 common sets of proposals, resulting in a total of 74 concrete actions. These 74 proposals were meant to implement the objectives that were laid down in the 2016 Joint Declaration. In order to evaluate the implementation of these proposals, the EU and NATO have published six progress reports since 2016.[15] It should be recognised, however, that the majority of the 74 proposals have a long-term perspective requiring continuous implementation, since they represent recurring processes which produce gradual results, rather than single one-off events.[16] Figure 1 presents a timeline of (recent) EU-NATO cooperation.

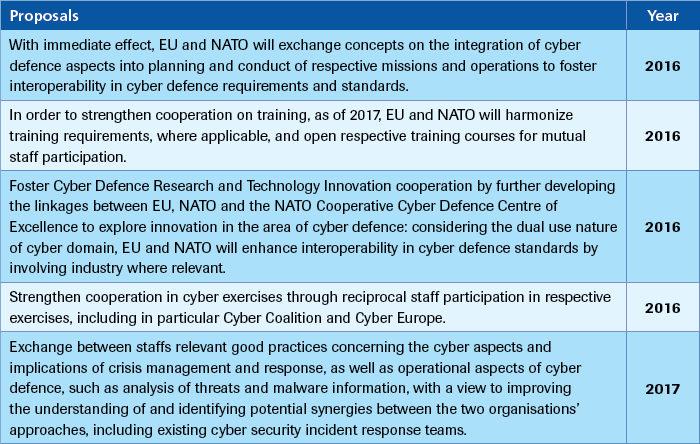

Countering hybrid threats is one of the main areas of cooperation between the EU and NATO: at least 20 out of the 74 proposals are related to countering hybrid threats. Taking into account cyber security and defence as a domain that is also of relevance for countering hybrid threats as well, this leads to a total of 22 out of the 74 proposals. Below, a reflection on these existing cooperation proposals and the progress that has been made is provided. As explained in chapter 2, the focus will be on the proposals that are highlighted under the topics ‘countering hybrid threats’ and ‘cyber security and defence’. Hence, the analysis will focus on the following sub-themes: situational awareness, strategic communication, crisis response, bolstering resilience, and cyber security and defence.

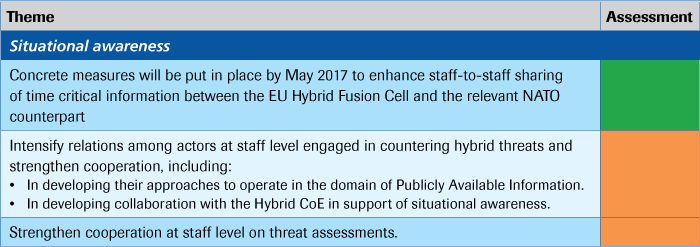

Situational awareness

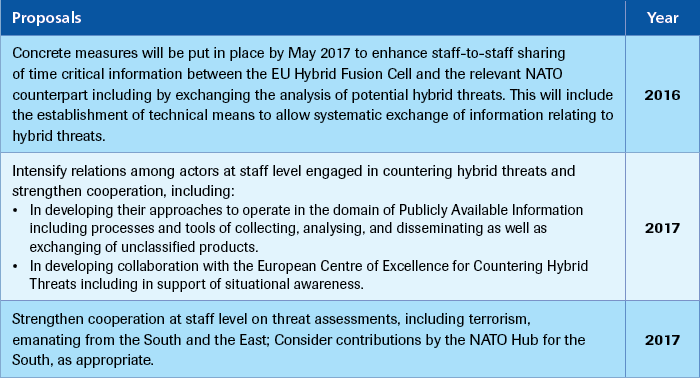

Situational awareness refers to being aware of relevant developments, events and threats that occur in a certain environment, including the geographical environment and cyberspace, that might affect a state’s or an organisation’s security.[17] It is well represented in the common set of proposals for EU-NATO cooperation. Out of the 74 proposals, three proposals (and two sub-proposals) concern situational awareness (see Table 1).

As for the first proposal on establishing concrete measures to enhance staff-to-staff sharing of information between the EU Hybrid Fusion Cell and the NATO Hybrid Analysis Branch, this was adequately followed up when both organisations drafted the 2017 proposals. In the 2017 proposals, more detailed measures for enhancing staff-to-staff sharing of information were incorporated. Therefore, it can be said that both organisations quickly complied with this 2016 proposal.

Mixed results have been achieved regarding the second proposal, the intensification of relations between those actors at staff level that are engaged in countering hybrid threats. A positive result is that staff-to-staff discussions have been established along geographical and thematic clusters of the EU’s Single Intelligence Analysis Capacity and NATO's Joint Intelligence and Security Division. This has contributed to the creation of a shared situational picture.[18] With reference to the first bullet of this proposal, the development of approaches to operate in the domain of publicly available information, some progress has been achieved: the EU Hybrid Fusion Cell and the NATO Hybrid Analytical Branch are exploring how best to make use of the Hybrid CoE for the exchange of publicly available information[19]; and the EU Hybrid Fusion Cell, the NATO Hybrid Analytical Branch and the Hybrid CoE are reflecting on the establishment of trilateral cooperation through open-source material.[20] It is however unclear whether and to what extent these two aspects have been materialised. In addition, during the conduct phase of a parallel and coordinated exercise, NATO liaison officers were hosted in EU premises and an EU liaison officer was deployed in NATO.[21] Moreover, video teleconferences between EU and NATO staff were organised to exchange information to enhance situational awareness. Progress has been made with reference to intensified cooperation in this domain, but these steps are so far relatively small and the most recent progress reports, the fifth and sixth, do not refer to any further progress with regard to the development of approaches for the exchange of publicly available information or the establishment of a trilateral cooperation forum.

Nevertheless, important steps have been taken to intensify relations between EU and NATO staff that are involved in countering hybrid threats. In essence, this comes down to the second element of this proposal, collaboration with the Hybrid CoE. The progress reports highlight that increased interaction can be witnessed between the staff of the EU Hybrid Fusion Cell, the NATO Hybrid Analysis Branch, and the Hybrid CoE. Concrete output in this regard are the high-level retreats, hosted by the Hybrid CoE, in which EU and NATO staff participated. In these retreats, which took place in 2018 and 2019, possible concrete actions and recommendations for further cooperation were formulated, including in the area of situational awareness.[22] This highlights that this format yields benefits, as it provides staff members of both EU and NATO with a forum in which they can update each other on their work, reflect on the progress made, and explore options for further cooperation. The literature supports this by stating that ‘cross-fertilisation’ in EU-NATO cooperation is occurring within the framework of the Hybrid CoE[23], the establishment of which is marked as a milestone in EU-NATO cooperation.[24]

Thirdly, and closely related to information sharing, is the proposal to strengthen cooperation on threat assessments. Threat assessments are important for creating situational awareness, as they provide a more detailed insight into existing threats, including into the actors involved. As reported, the general understanding on the nature of threats has increased over time and the views of the EU and NATO have converged.[25] Nevertheless, at present, there is no joint EU-NATO threat assessment. Both organisations have their own threat assessments, which to a certain extent align but also differ, building upon the different nature and operating regions of the organisations. Moreover, the age-old obstacle of sharing (classified) information and intelligence seriously hinders the creation of a joint EU-NATO threat assessment.[26] As information on hybrid threats is at least partly classified, such a joint assessment seems almost impossible. Logically, the progress reports do not substantiate any advancements that have been made in this area. Furthermore, the literature highlights the lack of information and intelligence sharing, emphasising that sharing information on situational awareness and open-source intelligence is required “to promote a shared view on our common security environment and events unfolding in it.”[27] The lack thereof indicates that increased cooperation on threat assessments has not progressed much in recent years, leaving room for improvement.

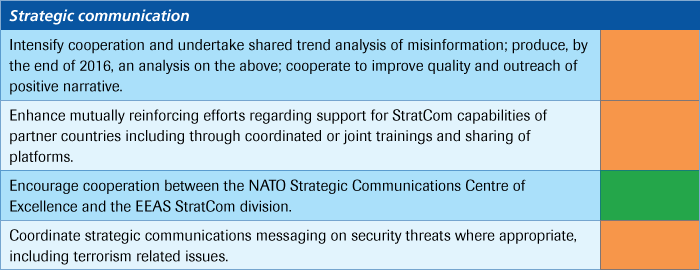

Strategic communication[28]

An important hybrid threat is disinformation creating distrust and disorder in societies. Both the EU and NATO are active in strategic communication to counter the threat of societal problems related to the spread of incorrect information. The NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence (StratCom CoE) describes the concept of strategic communications as follows: “A holistic approach to communication, based on values and interests, that encompasses everything an actor does to achieve objectives, in a contested environment. It means that strategic communication is understood more as a holistic mind-set in projecting one’s policies. We cannot focus on short-term, single-dimension, local issues. We have to think long-term, complex solutions, and effective ways of influencing big, important discourses in a very competitive environment. That is a permanent state of agility, whilst remaining true to own values.”[29]

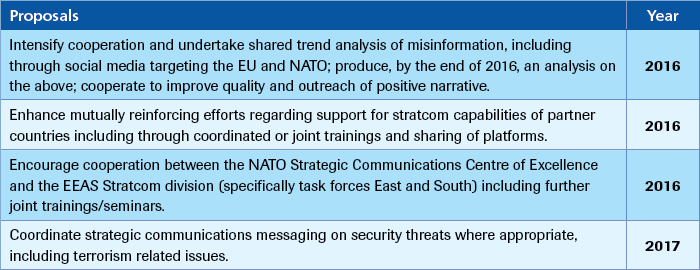

In 2016 and 2017 the EU and NATO articulated various proposals for increased cooperation on the topic of strategic communication (see Table 2). Based on the various progress reports that have been published, below the progress is reported for all four proposals on strategic communication.

First of all, progress is reported on the proposal to intensify EU and NATO cooperation and to undertake joint trend analysis of misinformation. The various progress reports list improvements in information exchange regarding strategic communication and the threat of misinformation. The increased exchange of information particularly takes place through formal and informal consultations and contacts between EU and NATO staff. Especially the establishment of the EU Hybrid Fusion Cell (created within the EU Intelligence and Situation Centre) in 2016 and its interaction with the NATO Hybrid Analysis Cell enabled a shared situational picture to be drawn up. This focused cooperation resulted in ‘Joint Intelligence Assessments’ as well as ‘Parallel and Coordinated Analyses’ in which disinformation threats were included. Furthermore, the EEAS, the European Parliament and the European Commission were regularly briefed by NATO officials, while EEAS officials were invited on different occasions to brief NATO staff on the strategic communication taskforces of the EEAS and on disinformation in particular.

A clear example of increased cooperation is offered by the Covid-19 pandemic during which disinformation surrounding the health crisis extensively increased: “EU and NATO staffs shared with each other dedicated Information Environment Assessments and held weekly calls with international partners such as the G7 Rapid Response Mechanism. NATO staff has shared with EU staff the NATO Covid-19 Strategic Communications Framework, the Covid-19 Integrated Communications Plan and a weekly selection of proactive communications products.”[30] This is also acknowledged in an article written by NATO Deputy Secretary General Mircea Geoana: “On Covid-19, there is regular top-level contact, briefing and information sharing. High Representative Josep Borrell recently attended the NATO Defence Ministers meeting and the Secretary General and I regularly attend EU meetings. Our strategic communications teams work together to combat disinformation and propaganda, and the NATO and EU disaster response coordination centres are in regular contact as they respond to requests for help.”[31]

Concerning the second aim, enhancing mutually reinforcing efforts regarding support for strategic communication capabilities of partner countries, including through coordinated or joint training and the sharing of platforms, the progress reports mainly mention consultations and calls to share information and ideas between EU and NATO staff. General capacity-building efforts in partner countries outside the EU and NATO, such as in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Moldova and Tunisia, often include elements of strategic communication. How to measure the level of success is difficult; according to some interviewees more improvement in this area could certainly be accomplished, although the ‘which and how’ remained unclear.

The Hybrid CoE in Helsinki has played an important role in encouraging cooperation between the NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence and the EEAS StratCom division. The main duties of the Centre are sharing best practices, testing new ideas and approaches, and providing training courses and exercises, including on strategic communication. The progress reports also mention continuous information exchanges between the EEAS StratCom division and the NATO StratCom Centre of Excellence in Riga, for instance on training materials, developing joint simulations and awareness-raising activities. An example is a jointly developed training course simulating disinformation attacks and responses delivered to EU staff. Although cooperation could be further deepened, the aim of encouraging cooperation was accomplished.

The fourth aim, concerning the coordination of strategic communications messaging on security threats, was accomplished but only to some extent; on this topic the progress reports particularly mention exchanges at the technical level of NATO and EU staff without going into much detail.

In general, the cooperation between the EU and NATO in the field of strategic communication seems to have increased in recent years, not least because of the Covid-19 crisis during which the spread of disinformation reached new levels. In the interviews this relatively positive image was confirmed, especially with regard to increased staff-to-staff contacts to exchange information. Yet, apart from mere information exchange, more practical cooperation in identifying and countering disinformation campaigns in a quick and effective manner is considered as a necessary next step for the coming years, also in more general terms that reach beyond the Covid-19 pandemic. A few publications touching upon the issue provide a similar perspective. Eitvydas Bajarūnas, Ambassador-at-Large at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Lithuania, praises the progress that both the EU and NATO have made in recent years in raising awareness for the relatively new phenomenon of large-scale disinformation, but also reiterates that much more efforts are required.[32] Hanna Smith, the Director of Strategic Planning and Responses at the Hybrid CoE, concluded in 2019 that: “In the area of strategic communication, people-to-people contacts have become frequent and common approaches have been explored, for example in relation to the Western Balkans and Europe’s eastern and southern flanks”.[33]

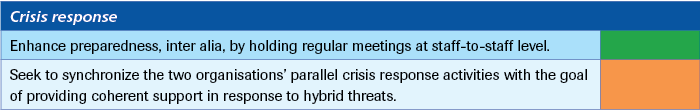

Crisis response

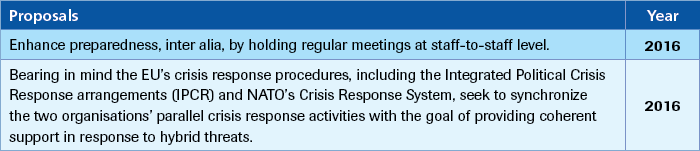

Out of the 74 concrete proposals for EU-NATO cooperation that have been created in 2016 and 2017, only two proposals are explicitly related to crisis response (see Table 3). However, proposals in other categories (for example in the cyber area), especially in relation to ‘exercises’, are relevant here as well, as these proposals have the objective of enhancing the crisis response activities of both organisations. Below, the progress that has been made with reference to EU-NATO cooperation in the field of crisis response will be outlined.

With respect to the first proposal, enhancing preparedness through regular meetings at staff-to-staff level, the EU and NATO have made important steps. Both NATO staff and EU staff actively participated in high-level retreats that were hosted by the Hybrid Centre of Excellence, where further actions for enhanced EU-NATO cooperation, including in the domain of crisis response, were specified.[34] Furthermore, various workshops and briefings in which both organisations participated were hosted to enhance staff-to-staff dialogue. Examples include: cross-briefings on EU crisis response mechanisms, NATO Counter Hybrid Support Teams, the European Medical Corps and capability development under the Civil Protection Mechanism; a workshop on EU-NATO cooperation in civil protection in February 2019; an intensified dialogue on CBRN issues; EU staff participating in the NATO Energy Security Roundtable in December 2017; and EU staff providing a briefing on energy security issues to the NATO Industrial Resources and Communications Services Group in March 2018.[35]

In addition, the EU and NATO have dedicated significant efforts over the past five years to improve the synchronisation of the EU’s and NATO’s crisis response activities. For example, NATO shared its guidance on Improving Resilience of National and Cross-Border Energy Networks and its guidance for Incidents Involving Mass Casualties with EU staff, thereby making better synchronisation between the EU and NATO possible.[36] The most remarkable effort in enhancing synchronisation, however, was the various EU-NATO exercises that took place. During the EU PACE17/CMX17 exercise in 2017, NATO staff were present at a Presidency-chaired Integrated Political Crisis Response arrangement (IPCR) roundtable, while EU-staff participated in the discussions of NATO’s Civil Emergency Planning Committee.[37] In November 2018, the EU Hybrid Exercise Multi-Layer 18 took place. This EU-led exercise was the largest crisis management exercise ever conducted with the aim of improving and enhancing the ability to respond to a complex crisis of a hybrid nature with an internal and an external dimension, as well as to improve cooperation with NATO. The exercise included a hybrid scenario designed to create meaningful interactions with NATO staff in the area of cyber security, disinformation and civil protection. Furthermore, EU staff participated in the May 2019 crisis management exercise of NATO, in which an EU Crisis Response Cell contributed to complement the crisis scenario with generic crisis responses from the EU institutions and the deployment of six EU staff members at NATO headquarters.[38]

The most recent example of an improved synchronisation of the crisis response activities of EU and NATO is the close coordination between both organisations during the Covid-19 pandemic. Various elements of the common set of proposals proved to be relevant in the context of the pandemic: countering disinformation, logistical support, responding to cyber threats and exploring the effects of the pandemic on operational engagements in theatres.[39] Moreover, NATO’s Euro-Atlantic Disaster Response Coordination Centre (EADRCC) and the EU’s Emergency Response Coordination Centre (ERCC) further intensified their cooperation and coordination during this period. In this regard they were able to build upon earlier practices in which the ERCC engaged in field exercises with the EADRCC.[40] Regular consultations and the continuous exchange of information on the organisations’ responses to the pandemic contributed to the creation of mutual situational awareness and helped to avoid unnecessary duplication. One very concrete output is the pandemic wargame ‘Resilient Response 20’, hosted by the Hybrid CoE in cooperation with the Multinational Medical Coordination Centre/European Medical Command and the German Federal Office of Civil Protection and Disaster Assistance. Both EU and NATO staff actively participated in this wargame[41], but it is still unclear what lessons have been learned and what it could entail for future cooperation in this area.

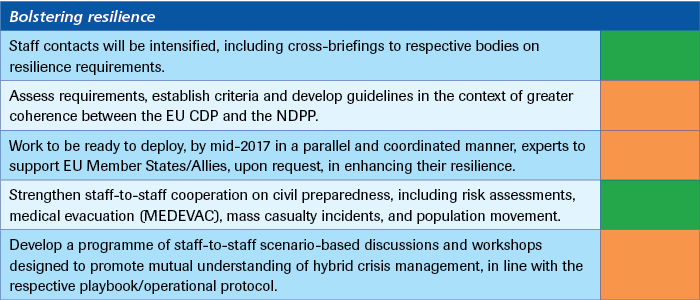

Bolstering resilience

As for hybrid threats, no single definition of resilience exists. It essentially comes down to states that possess the capacity and ability to minimise the potential disruptive impact that external shocks and events may have. The fluidity and broadness of the concept derives from the fact that ‘resilience’ needs constant adaptation following a continuously evolving international security environment.[42] The EU and NATO both have essential roles to play in enhancing resilience, abroad and at home. For the EU, the focus has primarily been on enhancing resilience abroad to safeguard security interests at home, incorporating it as a central element of the EU’s external policy framework. NATO regards Article 3 of its Treaty – namely that Allies should “maintain and develop their individual and collective capacity to resist an armed attack”[43] – as the reference for strengthening resilience.[44] Although the article was originally drafted to underline the importance of collective defence against the Soviet threat, today NATO has recognised that the changing security environment requires a broader perspective of an ‘armed attack’. Two clear expressions of this new interpretation can be derived from the Summit declarations of 2014 and 2021. The NATO Wales Summit of 2014 underlined that a cyberattack could also lead to the invocation of Article 5 of the NATO Treaty.[45] The NATO Brussels Summit of 2021 highlighted that Article 5 could also be called upon by a NATO ally in response to hybrid warfare.[46] However, non-traditional security threats require more than military responses. In contrast, these threats require broader societal resilience, something for which NATO is not necessarily well equipped – although Article 3 may suggest the opposite. In that sense, broader societal resilience is a relatively new domain for NATO, given that the organisation can primarily deploy military forces.

Both organisations therefore have a clear role to play when it comes to resilience. Logically, this has therefore been one of the focus areas where practical cooperation has increased in recent years. The concrete proposals for EU-NATO cooperation substantiate this, as no fewer than eight proposals are related to bolstering resilience (see Table 4).[47] Below, the progress that has been made with reference to EU-NATO cooperation in the field of bolstering resilience will be outlined.

As for the first proposal, staff-to-staff contact between EU and NATO staff members has clearly intensified in the past five years. With the exception of the first progress report, all reports mention that staff-to-staff contacts regarding resilience have continued over time. In addition, the reports mention that EU and NATO staff have participated in various cross-briefings and workshops, such as an EU-NATO Resilience Workshop and a NATO-hosted workshop on 5G networks and foreign direct investment.[48] The participation of EU and NATO staff in these workshops and scenario-based discussions also contributed to the fulfilment of the fifth proposal, to develop a programme of staff-to-staff scenario-based discussions and workshops to promote the mutual understanding of hybrid crisis management. In this respect, there is also room for improvement, which mainly comes down to embedding these workshops and scenario discussions more explicitly in EU-NATO cooperation, so that these become more regular exercises, instead of their currently more ad hoc nature.[49] Closely related is the facilitation role performed by the Hybrid CoE, thereby fulfilling the sixth proposal. The Hybrid CoE clearly fulfilled a hub function between EU and NATO staff by organising various scenario-based discussions, workshops and exercises.

Furthermore, in relation to the first proposal an important milestone was reached in 2020 when NATO international staff were included in the International Cooperation Space on the EU’s Rapid Alert System. The inclusion of NATO international staff in this forum allows for direct exchanges with EU member states and relevant EU institutions.[50] These developments have contributed to the improvement of staff-to-staff interaction, the exchange of information, increasing transparency and raising mutual awareness. Moreover, the Covid-19 pandemic provided a window of opportunity for both organisations to enhance staff-to-staff contacts on resilience and civil preparedness. EU and NATO staff continued to engage on these themes, including through the exchange of information on the organisations’ respective activities in response to the pandemic. In addition, the EU’s Emergency Response Coordination Centre (ERCC) and NATO’s counterpart, the EuroAtlantic Disaster Response Coordination Centre (EADRCC), closely cooperated throughout the pandemic, highlighting the benefit of previous joint field exercises.[51]

With reference to the second proposal, which dictates the establishment of greater coherence between the EU’s CDP and NATO’s NDPP, various efforts have been undertaken. For example, a staff-to-staff meeting was organised in May 2018, discussing and raising awareness of the status of the EU’s CDP and NATO’s NDPP and how resilience and hybrid threats were addressed in these two processes.[52] In addition, staff from both organisations participated in relevant events, including the NATO Defence Policy and Planning Symposium, contributing to further increasing transparency and raising awareness on the role of resilience in the two processes.[53] Moreover, regular contact between EU and NATO staff ensures the exchange of information on NATO’s baseline requirements for national resilience. Although these requirements have been shared with the EU, this does not yet guarantee that the EU automatically copy pastes all the requirements that are laid down. This has partly to do with the different nature of the organisations and the different instruments they have at their disposal to enhance resilience. Therefore, this can be a focus area to streamline EU-NATO cooperation further.[54] Moreover, a unique opportunity arises here, as the EU is in a position to create a legal framework for these standards with which EU member states have to abide.[55] This will eventually also benefit NATO. On a more general level, individual NATO Allies continued to invite EU staff for bilateral and multilateral consultations within the framework of the NDPP process, while EU member states that are also a member or partner of NATO invited NATO allies to attend (bilateral) meetings of the Coordinated Annual Review on Defence process.

As for the third proposal, establishing readiness to deploy experts to support EU member states and Allies in enhancing resilience, no concrete progress is mentioned in the evaluation reports. Nevertheless, NATO’s response to hybrid threats document, dating from 2018, states that NATO is ready to assist an ally at any stage of a hybrid campaign. The only prerequisite would be a North Atlantic Council (NAC) decision that allows NATO to do so. Moreover, the NAC could also decide to invoke Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty in cases of hybrid warfare.[56] This implies that NATO has taken the necessary measures to deploy experts at the request of member states. Two concrete examples where this has been put into practice are Montenegro (2019) and Lithuania (2021), where NATO supported both nations, at their request, in countering hybrid threats.[57] In the case of Lithuania, being an Ally and also an EU member state, it received NATO assistance. However, the fact remains that the progress reports do not mention that any progress has been made on EU-NATO cooperation in this area.

Progress has been made, though, with reference to the fourth proposal, strengthening staff-to-staff cooperation on civil preparedness. Staff from both organisations took part in various workshops, cross-briefings and table-top exercises, in which information was exchanged and guidelines, requirements and methods were shared.[58] Central themes were civil protection, critical infrastructure protection and foreign direct investment. An example includes NATO sharing its guidance for Incidents Involving Mass Casualties with EU staff.[59] More concretely, the EU’s and NATO’s medical communities enhanced their cooperation by cross-linking civilian and military expertise in medical-related topics, including a cross-briefing to evaluate potential synergies with reference to medical evacuation.[60] Next to the exchange of information on the organisations’ activities in response to the pandemic, the Commission, in September 2020, updated NATO’s Civil Emergency Planning Committee on the EU’s response to Covid-19, while NATO, in November 2020, shared with the EEAS and the Commission its updated Baseline Requirements for Resilience.[61]

The fact that NATO shared its Baseline Requirements for Resilience with the EEAS and the Commission is also in line with the seventh proposal, which prescribes that NATO and EU staff should map their civil preparedness efforts between NATO’s Resilience Baselines and the EU’s Prevention and Preparedness work-streams and outline additional proposals for increased cooperation. In addition, the staff of both organisations are sharing information regarding civil preparedness efforts between NATO’s Resilience Baselines and the EU’s Prevention and Preparedness work-streams. However, besides these two aspects the progress reports do not mention any further cooperation. Moreover, they also do not incorporate proposals where further cooperation may be of added value. Therefore, this proposal has only been partially fulfilled. This is confirmed by the interviews, in which it was highlighted that the only substantial accomplishment that has so far been achieved is the sharing of the Baseline Requirements. Although the sharing of the Baseline Requirements should be regarded as an important milestone, it is only a first step. It is up to the EU what the subsequent action will be and to what extent the organisation will make use of the existing NATO requirement. Moreover, besides the sharing of these requirements, further steps regarding enhanced cooperation have not been made and no concrete accomplishments have been achieved in this respect.[62]

With reference to the eighth and final proposal, it can be concluded that progress has been achieved. The proposal prescribes that, when appropriate, both organisations should explore the possibility to include EU staff in the NATO Resilience Advisory Support Teams and NATO staff in relevant EU advisory prevention and preparedness missions. Already in 2017, the EU participated as an observer in NATO’s advisory mission to Romania.[63] More structural cooperation was established in Ukraine, however, where experts from the EU’s Advisory Mission were part of the NATO-led team for Building Integrity Peer Review process for Ukraine. EU and NATO staff also coordinated their advisory support to Ukraine’s security and defence sector, with a specific focus on the reform of the security and intelligence services.[64] Another example is the cooperation between the EU Advisory Mission in Iraq and the NATO Mission Iraq. In this case, regular coordination took place in order to avoid duplication and to establish greater synergies. Both NATO and the EU have, in close cooperation with international partners, “developed a robust coordination and cooperation framework for the Security Sector Reform effort delineating roles and responsibilities”[65]. Other examples where EU and NATO staff closely coordinate in partner countries are Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Republic of Moldova and Georgia (on strategic communication and resilience).[66]

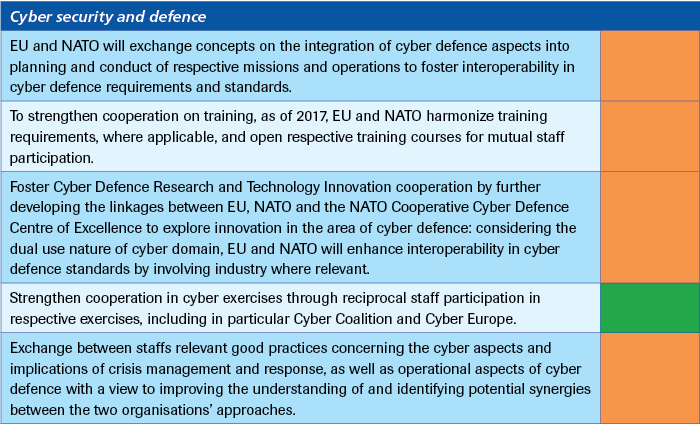

Cyber security and defence

Cyber security and defence is one of the main pillars of EU-NATO cooperation. In the sets of proposals of 2016 and 2017, five proposals are directly related to the area of cyber security and defence (see Table 5).

Regarding the first proposal on exchanging concepts and fostering interoperability, the progress reports list several exchange activities between the EU and NATO, such as meetings, joint workshops and other ways of information sharing. These activities took place at various staff levels, varying from, for example, high-level EU-NATO staff talks to cross-briefings by EU and NATO staff members in relevant Committees and/or Working Groups. According to the progress reports, these varying exchanges provided “a platform to establish a comprehensive overview of all mutually beneficial NATO and EU conceptual ideas and documents in the cyber domain and to explore their individual releasability as well as their potential for coordinated development.”[67] Whether the exchanges of information actually contributed to the increased integration of cyber defence aspects into planning or to more interoperability in cyber defence requirements and standards cannot be read from the progress reports. Interviewees acknowledged that exchanges between the EU and NATO have increased in recent years, and that this contributed to better interoperability, but it is hard to quantify the level of improvement that has been accomplished. More improvements in this field were considered to be possible and desirable.[68]

The second proposal, concerning harmonising training requirements and opening respective training courses for mutual EU-NATO staff participation, has been met to some extent: almost all progress reports include examples of EU and NATO staff participating in exercises organised by each other’s organisation, as well as joint workshops on education and training issues. While the opening of several training exercises for mutual participation is mentioned as a success, it is not clear whether, or to what extent, training requirements have been harmonised.[69]

The third proposal focussed on cooperation in Cyber Defence Research and Technology Innovation by further developing the linkages between the EU, NATO and the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence, and enhancing interoperability in cyber defence standards. Some progress reports mention that NATO staff were involved in EU staff efforts to develop generic standard operating procedures for cyber defence at headquarters level[70], and that ‘cyber’ was also the topic of an EU-NATO staff-to-staff dialogue on industrial aspects.[71] Yet, how far linkages and interoperability have actually improved is unclear.

The fourth proposal, on strengthening cooperation in cyber exercises through reciprocal staff participation in respective exercises, including in particular Cyber Coalition and Cyber Europe, partly overlaps with the second proposal on opening respective training courses for mutual EU-NATO staff participation. Several progress reports mention reciprocal EU-NATO staff participation in respective cyber defence exercises, so this aim seems to have been adequately accomplished.

The fifth proposal was on the exchange of good practices concerning cyber aspects and the implications of crisis management and response, as well as operational aspects of cyber defence, to enhance understanding and identifying potential synergies between EU and NATO approaches, including existing cyber security incident response teams. The progress reports describe many coordination meetings between EU and NATO staff, which are held at various levels on a regular basis, where exchanges on good practices have taken place. Moreover, the Technical Arrangement on Cyber Defence between the NATO Computer Incident Response Capability (NCIRC) and the EU Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT-EU) continued to be implemented in line with existing provisions, to which end the Malware Information Sharing Platform (MISP) was being leveraged.[72] Information exchange between CERT-EU and the NCIRC is listed as an accomplishment as well, including the organisation of a joint workshop on good practices. In the interviews conducted for this research, the progress regarding the exchange of information, including on good practices, was confirmed; the increased staff-to-staff level of communications might even be regarded as the most important progress regarding cyber security and defence. However, as will be discussed below, more efforts to improve effective information exchange are needed.

Although the progress reports sketch a positive image of increased EU-NATO cooperation in the field of cyber security and defence, in the (scarce) literature on the topic some more critical perspectives are offered. For example, in 2019 Piret Pernik of the Estonian Academy of Security Sciences stated that EU-NATO cooperation on cyber security and defence had made important strides, but that it proved difficult to engage the capitals “as top-level tangible activities are still needed to improve the common understanding of threats and the interoperability of national capabilities.”[73] Even though information exchanges and the sharing of threat assessments and resilience measures have improved, Pernik signals that “Brussels officials complain that these exchanges are bureaucratic, overly generic and lacking in substance.” An important problem in the cooperation, he suggests, is the limitation on sharing classified information, while such information is necessary to attribute cyberattacks with a sufficiently high level of confidence and to develop mutual trust. Next to the lack of sharing classified information, cooperation is hindered by different prioritisation. According to Pernik, NATO prioritises military doctrinal development and mission assurance, as well as integrating sovereign cyber effects to support NATO missions and operations. The EU, however, focuses on developing its cyber diplomacy tools, setting up a framework for the certification of ICT services and products, as well as creating stronger research and competence capabilities. Pernik further states: “Differences in state interests and in organisational memberships complicate taking meaningful common action. Countries differ in operational capabilities, the maturity of their national civilian and military cyber capabilities and their bilateral strategic partnerships with major cyber powers. Moreover, they have a variety of priorities and interests when it comes to protecting critical infrastructure and securing military assets.”

Bruno Lété, of the German Marshall Fund of the United States, also observes improved cooperation between EU and NATO in the field of cyber security. He states that “Since neither organisation possesses the full range of capabilities to tackle contemporary security challenges, there is a serious incentive for the EU and NATO to cooperate in times of crisis. And in the field of cybersecurity and defence the past few years have indeed brought significant change. The EU and NATO share many of the same priorities in cyberspace, their policies are largely identical – based on the principles of resilience, deterrence and defence – and their tools are becoming increasingly complementary.”[74] Concerning the successes of increased cooperation, Lété mentions exchanges between staff on concepts and doctrines, information on training and education courses, ad-hoc exchanges on threat assessments, cross-briefings, including on the cyber aspects of crisis management, and an annual high-level EU-NATO staff-to-staff dialogue. He also highlights the fact that since 2017 the EU and NATO flagship crisis management exercises – respectively called EU PACE and NATO CMX – are being coordinated and held in parallel with options for the mutual participation of EU and NATO staff.

In general, one may conclude that EU-NATO cooperation in the field of cyber security and defence has increased in recent years, but that external observers still see various obstacles to effective cooperation. Even if one should consider the cooperation proposals of 2016-2017 as modest first steps, much more bold steps will be needed to attain actual close cooperation, and an important question in this regard is whether the member states of both organisations actually desire such close cooperation. At this moment in time, there may be too little support in the various capitals.

Summary of the progress

Table 6 provides a summary of the assessment of existing EU-NATO cooperation with reference to countering hybrid threats. The assessment is based on a combination of the content of the Progress Reports, the literature and interviews with EU and NATO officials.

Obstacles to cooperation on hybrid threats

Since the beginning of EU-NATO cooperation, there have been obstacles that have hindered the optimalisation of cooperation, leading to sub-optimal outcomes. Some obstacles are age-old, others have emerged over time as a result of the changing security environment.

The first and most important obstacle to further cooperation is the organisations’ difference in member states. Although there is quite some overlap – 21 states are both a member of the EU and NATO – there are also EU countries that are not a NATO member and vice versa. The differences in membership are especially an obstacle when it comes to sharing more sensitive security-related information. It is common that some states only want to share information with either the EU or NATO, but not with both. Bruno Lété of the German Marshall Fund of the United States describes this as follows: “(…) the EU and NATO nevertheless remain two separate bodies, and each uphold restrictive information-sharing procedures that prevent the emergence of a culture of shared situational awareness or cyber threat assessment.”[75]

In practice, this problem is sometimes solved through sharing information only between EU and NATO staff, explicitly mentioning that information cannot be shared with representatives from member states. In such situations, NATO and EU staff are able to cooperate on the basis of this information, while at the same time individual member states do not receive the classified information. This way of information sharing has enabled the EU and NATO to circumvent certain (political) obstacles.[76] So far, this construction has worked for EU and NATO staff, but if joint EU-NATO follow-up action would be required, the involvement of member states cannot be avoided and political obstacles would then still prevail. Moreover, the absence of a secure communication system sometimes also makes this very difficult. Even if there is a willingness among EU and NATO staff to share sensitive or classified information, there is no quick and easy communication system to share this information. Moreover, the EU’s and NATO’s standards and practices in securing information also diverge[77], which further complicate matters. Therefore, this possibility of circumventing the (political) obstacles is no sustainable solution for the long term.

In addition to the difference in membership, the EU and NATO are also, by their very nature, different organisations. Whereas NATO is a political-military organisation, the EU deals with a much broader variety of policy areas and is a law-making organisation. Consequently, the EU and NATO have different toolboxes at their disposal that can be deployed in response to security threats. NATO possesses mainly military tools, while the EU can deploy civilian tools and military forces but the latter with serious limitations. This will not change fundamentally and practice shows that sometimes it takes a great deal of time to understand each other as definitions, context and responsibilities diverge. On the other hand, the different mandates and constitutions of the EU and NATO are the basis for complementarity and mutual reinforcement. This applies also to countering hybrid threats.

Another factor that hinders intensified cooperation is the changing security environment, which is increasingly characterised by hybrid threats. These threats cannot solely be addressed by military or civilian tools. In contrast, they require a whole-of-society approach, in which government and private actors must work together and where military and civilian tools need to be combined.[78] This is exactly why the EU and NATO, given their diverging toolboxes, could very well complement each other. In that context, the EU could primarily exhaust its civilian toolbox and to a lesser extent its military resources, while NATO can mainly provide resources from its military toolbox. Nevertheless, more is necessary in order to be able to counter hybrid threats effectively. The involvement of non-state actors, like private companies, is a field where both the EU and NATO as well as national governments often lack experience. Yet, the EU and NATO can prove to be a valuable part of the ‘whole-of-society’ chain when they create a joint platform where their respective member states can share information on hybrid threats. This will facilitate smoother cooperation between member states on countering hybrid threats, a necessity as no member state or organisation can address these threats by itself. In addition to functioning as a platform for their member states, the organisations can also enhance existing coordination between them to ensure smoother collaboration. It should, however, be prevented that cooperation will be experienced as forced, which runs the danger of reinforcing existing (political) obstacles.

Last but not least, there are obstacles on the member state level concerning non-traditional threats. Especially when it comes to hybrid cyber threats, various member states of the EU and NATO still consider cyberspace as a critical domain of national interest, and they are not always convinced that the EU or NATO should play a role here. Understandably, member states are reluctant to share all their threat intelligence or (technical) information on cyber incidents, information about their national cyber vulnerabilities and offensive or defensive cyber capabilities, or to put at common disposal their technical and intelligence capabilities to attribute cyber incidents. In addition, the cyber capabilities of the various member states are often not interoperable nor complementary, which implies that there is a growing gap across member states in terms of both civilian and military cyber capabilities.[79]

Assessment

In general terms, EU-NATO cooperation in countering hybrid threats has improved in recent years. In particular, improved staff-to-staff contacts, the structured (political) dialogue and joint exercises can be highlighted as important results. In addition, both organisations have worked hard towards creating shared situational awareness, in particular through making use of the Hybrid CoE. However, obstacles to enhanced EU-NATO cooperation still exist. Some of these obstacles might be overcome in due course – such as recognising the different nature of both organisations – but others are likely to remain, at least for the foreseeable future. The political blockade caused by the Turkey-Cyprus issue is the key factor that hinders a better use of the formal cooperation channels and continues to block the exchange of classified information.

Despite these obstacles there is still room for a further improvement of EU-NATO cooperation in countering hybrid threats. Various of the common proposals dating from 2016-2017 have not yet been (fully) implemented, leaving sufficient opportunities for further cooperation between both organisations. Experts emphasise, however, that advanced EU-NATO cooperation on hybrid threats is a long-term process that takes time and should be met with patience. They underscore the importance of the cooperation efforts within the EU-NATO framework and warn against alternative cooperation formats. Moreover, it was highlighted that, often, strategic vision behind counter-hybrid efforts is lacking. The focus tends to lie on finding appropriate responses to the deployment of hybrid tools, while less attention is paid to the actors’ objectives and intentions behind the use of these hybrid tools.[80] Adopting a more strategic approach, in which more focus would be directed towards the objectives and intentions of (potential) adversaries, could benefit both organisations in the long run. Nevertheless, one should not cling too much to the EU-NATO framework, without considering alternative formats of international cooperation on countering hybrid threats, which are included in the next chapter.