A. Regional connectivity

Inherited from colonial powers, borders in the Sahara have divided the pre-colonial territories of some of the main desert communities, including the Tuareg (straddling the borders between Algeria, Mali, Niger and Libya), Tubu and Goran (living in Chad, Niger and Libya) and Zaghawa (in Chad and Sudan). Other communities have moved, or sometimes been forcibly removed, across considerable distances and are now scattered over several territories – for example, the Awlad Suleiman (scattered between Libya, Niger and Chad) and Rizeigat Arabs (spread between Sudan, Chad and Niger).

Except for Chad, where Tubu, Goran and Zaghawa rebel leaders have successively taken power since 1979, none of these pastoralist communities have benefitted from consistent representation or power within central governments in any of the countries where they live. Rather, they have managed, including through their ability to cross borders and thus find rear bases and support for their armed groups, to exert an important degree of control over borderlands and cross-border routes, each community mostly controlling its own traditional homeland.

This largely explains why these communities have, for decades, engaged in smuggling licit or illicit goods across borders, as well as facilitating the journeys of migrants travelling to North Africa and eventually Europe.[3] During Qaddafi’s rule, members of those communities were not only smugglers but also took part themselves, alongside members of other Nigerien, Chadian and Sudanese ethnic groups, in ‘circular’ migration flows to Libya. Most worked in agriculture or construction and sent remittances to their countries of origin before their return, often after several years away. Others remained in Libya and formed diasporas. Many also became back-up combatants for Qaddafi’s forces.

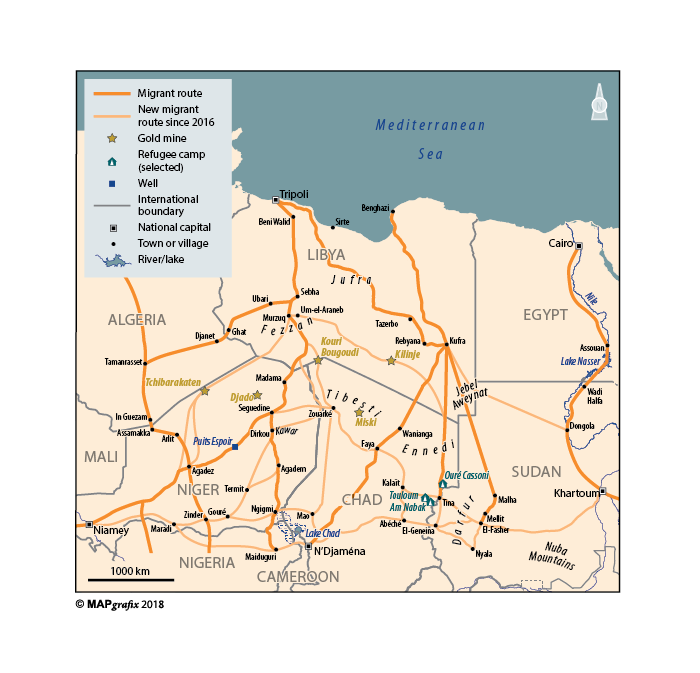

Lately, cross-border dynamics and regional similarities have been reinforced by a spectacular series of gold rushes across the Sahel and the Sahara. Beginning in North Darfur in 2012, gold was also discovered that same year to the west in the Chad-Libya borderlands, then in northern Niger and its border with Algeria in 2014.[4] Migrants sometimes worked in gold mines to fund their journey, but gold mines also acted as an economic alternative to migration, while the closure of gold mines encouraged further migration. In addition, vehicles rushing to gold mines transported both workers and migrants, and some cross-border gold mines became new migration hubs, as detailed below in the case of Chad.

Gold mines across five countries (Sudan, Chad, Niger, Libya and Algeria) have particularly attracted more experienced Darfurian miners, including Zaghawa – among them members or former members of Darfur rebel movements. Rebels and former rebels from both Darfur and Chad are also among mercenaries hiring their military and desert skills in Libya, road bandits active in Libya and Niger, drug traffickers between Niger and Libya, and smugglers of both goods and migrants between Libya and the three countries south of it.

The three countries south of Libya differed in their relations with Qaddafi’s Libya, and thus in their positions on the 2011 Libyan revolution and their relations with factions which have emerged since. They had a similar history, however, of being main places of origin for those migrants who mostly travelled to Libya, rather than to Europe, in order to work there, often seasonally, and send remittances home. In 2018, according to International Organization for Migration (IOM), Niger, Chad and Sudan were the first origin countries of 575,000 sub-Saharan migrants numbered in Libya (actual numbers are likely to be much higher), representing 18%, 15% and 10% of the total, respectively.[5] However, some of those migrants – mostly Sudanese, with 6,221 arrivals in Italy in 2017 – are now increasingly continuing their journey across the Mediterranean, often without having planned for it initially but pushed by the insecurity and violence they experience in Libya.[6]

Beyond well-established common circular migration patterns, the three states south of Libya are also, to various extents, transit countries for migrants from other countries on their way to Libya and eventually Europe. Niger is the main transit country for West African, largely economic, migrants, with a peak near 400,000 in 2016.[7] Sudan is both a main country of origin and a transit country for a smaller number of migrants from the entire Horn of Africa, largely fleeing wars and authoritarian regimes across the region. Chad is only, although increasingly, a secondary transit country for migrants from central, east and west Africa (as will be discussed in more detail below).

Migrants often do not know for certain their final destination when they leave, and only a few of those reaching Libya are aiming for Europe and travel to Europe. What they do largely depends on the security and economic situation they face once in Libya. Under Qaddafi, Libya was a relatively safe place for migrants, a place where sub-Saharan economic migrants could find work, earn money and send remittances home. It was also a place where political refugees from countries not friendly to Libya could find refuge – despite the fact that Libya had no asylum law – and eventually support for their cause, without necessarily travelling to Europe.

Qaddafi himself had proved a master at regulating migrant flows, sometimes violently preventing migrants from leaving Libya by sea, and at other times opening borders and threatening Europe with an African ‘invasion’. The Libyan ‘Brotherly Leader and Guide of the Revolution’ thus used African diasporas on his soil as a bargaining chip to get both political and financial support from European governments already panicked by the far right’s electoral successes. This lesson has been learned by Libyan rival factions, competing to get international recognition and support. Further south, sub-Saharan governments also well understand that the refugee crisis gives them a chance to gain leverage over Europe and obtain further political and financial support.

Indeed, Sudan, Chad and Niger had already excelled at presenting themselves as the West’s allies against terrorism in order to get both political and economic support. As early as 2001, following the September 11th attacks, Sudan, although then considered a sponsor of terrorism, was quick to turn this disadvantage into an opportunity, proposing intelligence cooperation with the US against terrorism – cooperation that has been ongoing since. More recently, in 2017, the pursuit or reinforcement of this cooperation has been one, if not the main, criterion for the withdrawal of US economic sanctions against Sudan.

Similarly, both Chad and Niger have been key allies of the West – mostly France and the United States – against jihadi groups in the Sahel. Chadian forces were the backbone of international interventions in Mali and against Boko Haram. Both Chad and Niger also welcomed Western forces on their soil and presented themselves as enclaves of stability in a fragile Sahelan strip. Those activities allowed Niger, Chad and Sudan to become crucial regional allies of the West. The migration issue offers another opportunity to reinforce such support, crucially for three states – Sudan, Chad, and Niger – that are facing economic crises and badly in need of hard currency.

In recent years, migration has led to European financial and economic support to Niger and Sudan, notably with amounts of around EUR 200 million dedicated to migration in each country. However, as the political situation in those countries differs, the funding is not used in the same way. At peace for ten years and more democratic, Niger was seen as a model recipient: European funds there are largely distributed to the government itself, for uses including the reinforcement of security forces, and mostly dedicated to directly stopping migration flows.

But in war-torn and undemocratic Sudan, where conflicts and authoritarian rule have caused the displacement of several million citizens, Europe was arguably more cautious. Its funds are largely aimed at rather classical development projects addressing ‘root causes’ of migration, and managed through implementing agencies, mostly from EU member states. Yet the EUR 40 million ‘Better Migration Management’ programme that the EU adopted under the Khartoum Process includes Sudan as one its target countries. Under this programme, the EU invests in ‘the provision of capacity building to government institutions’ as well as ‘harmonising policies’ and laws against ‘trafficking and smuggling’, and ‘ensuring protection of victims and raising awareness’.[8]

EU member states, including Italy, Germany, France and the United Kingdom, have also engaged bilaterally with the governments of Niger, Chad and/or Sudan, with a focus on strengthening border control.

The three states south of Libya and Libyan rival powers have their own interests in terms of border management or control, differing from European priorities and among themselves. There has been little cooperation between them so far, with the exception of the Chad-Sudan joint border force created in 2010 to put an end to five years of proxy war and rein in both Chadian and Sudanese rebels.[9] Recently, on 31 May 2018, Niger, Chad, Sudan and the Libyan GNA signed a security cooperation agreement in N’Djaména after several meetings. The agreement mirrors and expands the 2010 Chad-Sudan arrangements. It includes notably a right of pursuit for one country’s forces into a neighbour’s territory, which Chad has already used to chase Darfur rebels crossing from Chad to Sudan. It also invites the four countries’ judiciaries to sign, within two months, other cooperation agreements facilitating extraditions.[10]

This provision responds very much to a Chadian demand to give a legal framework to extraditions of Chadian rebels to Chad, which had already taken place in the past – including from Niger and Sudan, in 2017 and 2018 respectively. While diverging interests reportedly prevented strong practical commitments, there were some common interests, such as the similar Chadian and Sudanese priorities to prevent their respective (and sometimes allied) rebellions to find support in Libya, and the Nigerien concerns about the presence of Chadian and Sudanese armed groups on its territory.[11]

B. Chad and the regional diversification of migration routes

The implementation of border controls and anti-smuggling operations in Niger and Sudan has resulted in the diversification of migration and smuggling routes in the region. One effect of anti-migration policies in Niger, for example, has been the push of West African migrants toward Chad. Although no reliable figures are available, the numbers of West Africans, in particular Malians and Senegalese, crossing Chad into Libya appear to have increased in 2017-18.[12]

Our interviews with newly arrived migrants in Europe and migrants and smugglers in Chad and Niger (see Appendix for this study’s methodology) confirm that migration routes have diversified. Some migrants travelled to Chad after being arrested in Niger and expelled. In March 2018, for example, H.S., a Burkinabe migrant, reached the Chadian capital, N’Djaména, by road from Niger. Prior to this, on his way to Libya, he had been arrested in Agadez by the Nigerien police and imprisoned for two days. He had then been given three days to leave Agadez, and threatened, if he did not comply, with a five-year prison sentence.[13] From N’Djaména, he was planning to travel north towards Libya.

Other West Africans now travel through Nigeria and Cameroon to N’Djaména before they head north to Faya. Others cross the Niger-Chad border, either north of Lake Chad, toward Mao, or further north, to reach the Tibesti Mountains at the border with Libya. Some even cross Chad all the way to the Chad-Sudan border, or even enter Sudan, to use routes going from there to Libya.[14] A migrant smuggler in Tina, on the Chad-Sudan border, explained: ‘Some West African migrants who have been blocked in Niger try their luck here.’[15] There are also reports of an increase in Sudanese smugglers in Agadez itself, who have come to organise the journeys of West African migrants through Chad and Darfur.[16]

In a similar vein, the increase in border controls on the direct routes from Sudan to Libya has resulted in a number of migrants now first crossing the Sudan-Chad border before heading to Libya through Chadian territory.[17] Since 2017, it reportedly became the most important route between Sudan and Libya.[18] Old and new routes between Chad and Libya have recently been used by migrants not only from Sudan but, more unusually, from the entire Horn of Africa. Ethiopian migrants interviewed in Tina, on the Chad-Sudan border, in March 2018, explained: ‘In January, we left Khartoum for Tina because we were informed that this route is easier than the direct route from Khartoum to Libya, on which there are many controls.’[19] Some migrants decide to travel through Chad after being intercepted at border controls in Sudan; one who did so was Y.A., a Sudanese asylum seeker, who reached Tina after being arrested and tortured for ransom by Sudanese government-backed militia forces in charge of controls in the border regions with Libya and Egypt.[20]

In recent years, notably as a result of anti-migrant policies in both Niger and Sudan, Chad has become a new transit country for both West African and East African migrants. Migrants from countries such as Senegal, Mali, Liberia, Somalia and Eritrea, who were rarely seen in Chad in the past, are now crossing the country towards Libya.[21] It does not appear that Chad has become the next big migration hub, but the growing number of migrants passing through Chad does show that nationally focused migration policies tend to result in the displacement of routes rather than in stopping migration completely. This may have important consequences for the stability of neighbouring countries caught unaware by such dynamics, as the case of Darfurian refugees in Agadez (discussed below) illustrates.

C. The regional diversification of refugee routes: Sudanese asylum seekers in Agadez

Since December 2017, there has been an unexpected influx of Sudanese in Agadez, reaching close to 2,000 people in May 2018.[22] Most are Darfurians coming from southern Libya. Some also came through Chad, from Darfur itself, from Darfur refugee camps in Chad, or from gold mines in northern Chad.[23] Those who came through Chad include the wives and children of men who had come earlier from Libya. Most of those Sudanese were moving through Libya or Chad, and its seems their movements were redirected to Agadez by UNHCR’s presence there, particularly with the opening of ‘guesthouses’ in January, and more crucially with the possibility that asylum seekers evacuated from Libya would be resettled in Europe.[24]

‘Until the end of last year, we didn’t have any idea to go to Niger, until we heard the UNHCR opened camps in Niger to resettle people outside Africa, in Europe and America’, explained a Sudanese refugee in Agadez.[25]

These rumours referred to the more than 1,000 migrants, notably Darfurians, identified as possible asylum seekers, which had been evacuated from Libya to Niamey after November 2017. EU member states had promised to grant them asylum.

The Sudanese influx in Agadez is another unintended consequence of migration policies based on a country-specific than a regional approach. Beyond the ‘pull factor’, it seems the fact that crossing the Mediterranean has become increasingly difficult has acted as a push factor to Niger for Darfurian refugees in Libya.[26] ‘I just wanted to cross the Mediterranean to go to Europe,’ explains B., one of the Darfurians in Niger, who left Sudan to Libya in 2017. ‘But it’s difficult. Now people know everyday the EU prevents people to cross. As Darfurians, we are refugees and we thought it would be better to come to Europe legally. We heard the UNHCR offered good services in Agadez and could take us somewhere else, in Europe. Some of us also heard the French government gave asylum in Niger.’[27]

An additional pull factor is indeed that, since October 2017, French asylum authorities sent officers to both Niamey and N’Djaména, in order to interview asylum seekers there, after pre-selection by UNHCR – the first time such missions have been sent to Africa. The aim is to resettle 3,000 refugees in France.[28]

Both the Nigerien government and local communities in Agadez viewed the Sudanese presence with suspicion.[29] Before their arrival, there had been, since 2016, an increase of carjacking in north-eastern Niger on the road between Dirkou and Libya. This was largely attributed to Darfurian and Chadian Zaghawa, including rebels and former rebels operating from Libya. Members of the Chadian army based in Tibesti were also accused. Those new foreign armed groups also attacked drug traffickers before being asked to escort drug convoys across northern Niger, thus competing with local Tuareg and Tubu youths involved in this activity.

Prior to this, since 2014, there had also been an influx of Darfurian and Chadian Zaghawa gold miners in the newly discovered Djado gold mines mid-way between Dirkou and Libya, and to a lesser extent the Tchibarakaten mine on the Niger-Algeria border. Those miners included rebels, former rebels and Chadian soldiers. With more experience in gold mining, the Darfurians aroused jealousy from Nigerien miners and local residents, triggering some deadly incidents.

As soon as the Sudanese asylum seekers arrived in Agadez, Nigerien authorities characterised them as ‘criminals’, ‘fighters’, ‘possible members of armed groups in Libya’ and ‘ex-mercenaries who fought in Libya’, and claimed they were transiting to Niger on their way to other conflict theatres to offer their services as mercenaries.[30] To the EU, they were even presented as ‘jihadists’.[31]

In May 2018, some of those (unconfirmed) allegations were used by Niger as a justification to deport 135 of the asylum seekers back to the Libyan border, which constitutes a violation of the non-refoulement principle.[32] They were forcibly driven to Madama, the northernmost Nigerien (and French) garrison, 80km from the Libyan border. Those left in Agadez managed to contact Sudanese traders in Um-el-Araneb, in southern Libya, who sent trucks to drive the expelled Sudanese to Libya, for the price of XOF 6,000 (EUR 9) each. This incident goes completely against EU policies aimed at preventing migrants from entering Libya and also questioned the EU’s depiction of Niger as a ‘safe country’ in which to relocate migrants returned from Libya.[33]

Sudanese refugees in Niger were also reportedly threatened with deportation to Sudan – which, according to B., ‘is the great fear’.[34] Fearing new arrests, many reportedly returned to Libya or Chad of their own volition. By late June 2018, the number of Sudanese in Agadez had decreased to 1,200.[35]