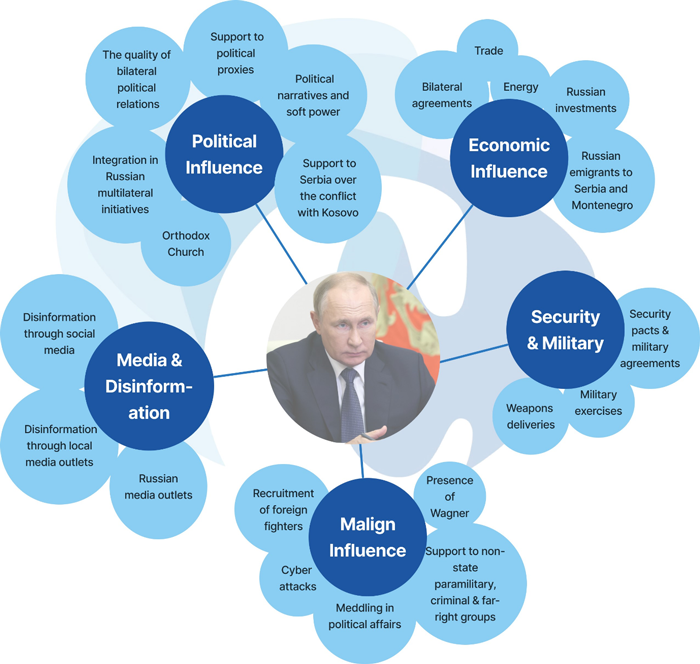

Russia employs a range of tools to influence the course of events in Serbia, Montenegro, and Bosnia and Herzegovina. This chapter presents an analysis of such tools, taking into account Russian political influence, economic influence, its influence through security and military cooperation, Russian malign influence, and its influence through the media and disinformation. Figure 2 is an overview of the factors discussed. Russian and local actors through which Russia maintains a grip on the region are discussed throughout the sections.

Russia’s political influence in Serbia, Montenegro, and Bosnia and Herzegovina

Although the Western Balkans are not of central importance to Russian foreign policy, Russia has forged political links with Serbia, Montenegro and BiH that provide it with varying degrees of leverage. Apart from government-to-government relations, Russia has committed to building relations with political proxies, thereby employing consistent political narratives revolving around traditional values and pan-Slavism. The Kremlin’s position on Kosovo in particular has yielded influence among ethnic Serb politicians and societies in the three countries. Lastly, links with the Orthodox Church amplify pro-Russian political narratives in the region.

Political relations

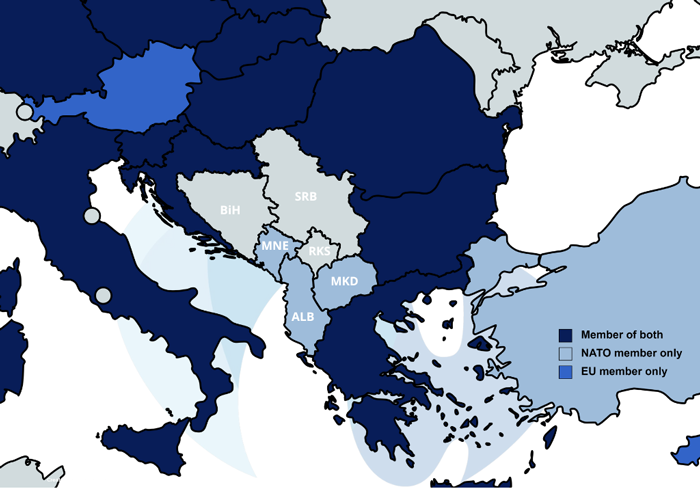

In terms of political integration, BiH, Serbia and Montenegro have, as a result of their years-long EU accession processes, a far more institutionalised relationship with the EU than with Russia. Russian-led multilateral efforts like the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), and the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) do not stretch to the Western Balkans, with two partial exceptions: Serbia’s observer status in the CSTO and its free-trade agreement with the EEU.[35] While simultaneously being connected to these initiatives and negotiating accession to the EU, Serbia is also keen to nurture relations with other regions, as exemplified by its hosting of the Non-Aligned Movement summit in 2021.[36]

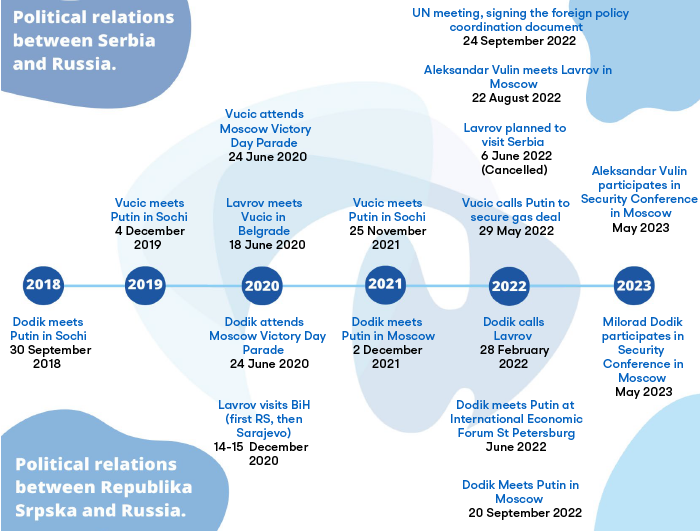

In the absence of strong multilateral frameworks, relations between the three south-eastern European states and Russia are predominantly forged through bilateral cooperation. There are strong differences between the countries, as is clear from the number of bilateral meetings, as shown in Figure 3. Russian-Serbian relations are marked by declarations of like-mindedness, historical partnership, and brotherhood. Serbia and Russia have signed cooperation agreements on numerous issues, ranging from trade, defence, foreign policy and energy to visa-free travel. Montenegro, on the other hand, is on Russia’s list of so-called non-friendly states, and, especially after it joined NATO, largely regarded by Moscow as an adversary rather than ally.[37] BiH’s state-level relations with Russia are limited. Instead, engagement is mostly through the Republika Srpska (RS) entity. RS-Russia relations are perhaps even more explicit than Serbian-Russian relations, mainly because the RS political leadership, impersonated by the entity’s long-term ruler, Milorad Dodik, expresses strong ‘demand’ for such Russian influence.[38] In the past five years, Dodik has visited Moscow more times than any other European politician. He decorated Putin with the highest RS medal of honour in January 2023 and was decorated by Putin with the Order of Alexander Newysk in June 2023.[39]

Differences between Montenegro, BiH and Serbia are also apparent in their responses and actions following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Whereas the three countries all voted to condemn Russian aggression on Ukraine in a United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) vote early March 2022, follow-up actions have differed.[40] Montenegro has fully aligned with EU sanctions on Russia since 2014, whereas Serbia has hinted at but so far refused to impose any sanctions.[41] Also, BiH has failed to impose sanctions, mainly because of resistance from RS leader Milorad Dodik, who on the contrary sought to intensify economic relations with Russia following its invasion of Ukraine.[42]

Influence through political proxies

Importantly, Russian political influence in Serbia, Montenegro, and Bosnia and Herzegovina is not all-encompassing, but, particularly in Montenegro and BiH, is wielded through political proxies representing only part of the political spectrum. Even among these proxies, different levels of Russia-mindedness can be observed, with most of them being primarily self-interested and some actively searching to balance relations with other external powers also. Russia has, however, become reliant on certain proxies to such an extent that it continuously supports them in spite of their dominantly self-interested agendas, which often, but not always, overlap with Russian objectives.[43]

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, Russia relies strongly on RS president and leader of the Bosnian-Serb party SNSD (Alliance of Independent Social Democrats) Milorad Dodik, who has presented himself for years as the Balkan leader most loyal to Moscow.[44] Russia has in the past directly financed Dodik’s elections campaigns and, according to an expert, the country is the prime investor in RS, although that does not appear in official statistics.[45] Apart from Dodik, other politicians in RS, for example Nenad Stevandić from the United Srpska (US) party, can also be regarded as pro-Russian.[46]

Russia’s support for RS politicians is clear for several reasons, for example from the behaviour of its ambassador Igor Kalbukhov, who attended the 9 January RS parade in Banja Luka in spite of a ban by BiH’s highest court. Kalbukhov also threatened that Russia would be forced to take action if BiH takes steps towards NATO integration. At the same time, also in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, political forces like the Bosnian-Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) of Dragan Čović sometimes act in the Russian interest, for example when Čović and his fellow HDZ senators voted against aligning with EU sanctions towards Russia in BiH’s House of Peoples.[47] Moreover, on 23 June 2023 the US Embassy in BiH condemned Čović for obstructing the Southern Interconnection natural gas pipeline, which would reduce BiH dependence on Russian gas, declaring that ‘BiH is at energy crossroads, and HDZ BiH is blocking the path to European integration and energy security.’[48] In Montenegro, Russia became more influential in 2020 when pro-Russian and pro-Serbian parties ousted the long-term parliamentary dominance of the Democratic Party of Socialists (DPS), headed by long-term president Milo Đukanović. In particular, the Za budućnost Crne Gore (For the Future of Montenegro) movement of Andrija Mandic and Milan Knežević, formerly known as the Democratic Front Alliance, garnered about 15% of the votes in the 2023 parliamentary elections and can be regarded as pro-Russian. There is proof of direct funding from the Kremlin for the parties making up the alliance.[49] Their politicians campaigned against Montenegro’s NATO integration, visited Moscow for meetings with Russian politicians in 2016, and signed the so-called Lovćen Declaration on cooperation between Knežević’ Democratic People's Party and the United Russia party.[50] They were also convicted in a first-instance verdict for their alleged participation in the 2016 coup attempt, although a retrial will be held after a higher court overturned that decision due to procedural mistakes.[51]

On the other hand, the Europe Now! Movement of the April 2023 elected president Jakov Milatović, who ousted long-term DPS leader Milo Đukanović from power, is nominally firmly focused on EU integration and domestic reforms. Europe Now!, which won the most seats in the June 2023 parliamentary elections, has, however, also taken a more pro-Serb position in the Orthodox Church rifts that split Montenegro in the past few years, and different factions within the party have different geopolitical outlooks.[52] As numerous unknowns remain regarding Europe Now’s orientation, time will be needed to realistically assess their actual goals and policies.

In Serbia, a larger proportion of the political scene has forged strong ties with Russia. Russia’s position as a UN Security Council member that supports Serbia’s position on Kosovo is the main source of Russian influence over Serbia’s political landscape. It largely explains why the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) government of President Aleksandar Vučić has openly pursued a Russia-friendly foreign policy, including after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The previous Minister of Internal Affairs and current head of Serbia’s Security Intelligence Agency, Aleksander Vulin, is perhaps the most outspoken and influential pro-Russian political actor in the country. He travelled to meet Lavrov in Moscow in August 2022 and is suspected of delivering wiretaps of a Russian opposition meeting in Belgrade to Russia’s Security Council Secretary Patrushev.[53] Coalition partner SPS (Socialist Party of Serbia), led by Ivica Dačić, is generally regarded as pro-Russian as well.

A more extreme far-right proxy exists in the form of the Serbian Radical Party (SRS) of Vojislav Šešelj, a far-right war criminal convicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and once regarded as the political mentor of current president Vučić. Although his party is currently not represented in Parliament, far right parties have not disappeared from Serbia’s political scene. The ultra-nationalist party Srpska stranka Zavetnici, or Serbian Party Oathkeepers (SSZ), led by Milica Đurđević Stamenkovski, retains an openly pro-Russian and anti-NATO course. Other factions, such as the National Democratic Alternative (NADA) and Dveri-POKS, also pursue nationalistic conservative agendas, for example advocating for the reintegration of Kosovo.

Russian support for far-right Serb political forces has a destabilising effect not only in Serbia but also in its neighbouring countries. That is because these politicians (as well as nationalistic proxy groups) generally hold positive views on the creation of a Greater Serbia as propagated in the 1990s by former Serb president Milošević, or Srpski Svet (Serbian world), a term forged in 2014 and similar to the irredentist ideology of the Russkiy Mir (Russian world). By supporting these actors, Russia undermines the stability and the sovereignty of neighbouring countries like Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo and Montenegro.[54] Such ideologies also constitute an important aspect of Serbia’s non-recognition of Kosovo, which hosts a considerable Serbian community as well as many sites of the Serbian Orthodox Church.

Russian political narratives

Russia employs various narratives in its approach towards Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro and Serbia that resonate well with substantial sections of their populations. The central notions of these narratives revolve around the ideas of: a) Russia as the defender of Christian-Orthodox traditional values; b) a pan-Slavic link between the peoples of Russia and the Western Balkans; c) the degeneration of the collective West; d) a need for strong leaders ready to defend their country and values in today’s world; e) NATO expansion as a cause for the war in Ukraine; and f) territorial integrity as an argument for support of Serbia’s position on Kosovo.[55]

Such narratives resonate well in some sections of society in all three countries, given their conservative nature and lack of longstanding democratic tradition, as well as a sense of disappointment with EU integration after what many consider as 20 years in the EU ‘waiting room’. [56] However, importantly, support for the EU and Russia are not necessarily communicating vessels, meaning that those who are pro-EU are not necessarily anti-Russian, and vice-versa.. Besides, while many people in the three countries support narratives on conservative values, at the same time they mock Russia’s performance on the battlefield in Ukraine.[57] It would be too much of a simplification to classify people as simply pro-Russian or pro-EU, as such classifications fail to account for local interests and orientations.

Political influence through the Orthodox Church

A particularly visible actor in spreading Russian narratives is the Serbian Orthodox Church, estimated to have about 8 million members of which most in the three countries examined, thereby having substantial societal influence.[58] De jure, the Serbian Orthodox Church is autocephalous and as such not subordinated to the Patriarchate in Moscow. De facto, the Serbian Orthodox Church retains close ties with the Russian Orthodox Church, which is closely connected with the Kremlin and has presented itself as a solid supporter of Russia’s foreign policies, including its invasion of Ukraine.

Russian influence through the Orthodox Church works in several ways. First, the Serbian Orthodox Church replicates a large part of the Russian narratives presented above, thereby not only spreading conservative values but also political viewpoints of partnership between Russia and the three countries. It ‘provides religious legitimacy to domestic and foreign state policies’ in Serbia, but also promotes Serb nationalism and anti-Western agendas in Montenegro and BiH, for example when it campaigned strongly against Montenegro’s 2017 NATO accession.[59]

Second, Russia actively amplifies church rifts in the region to sow division and destabilise societies at large. For example, in Montenegro, a separate Montenegrin Orthodox Church exists, but it is not recognised by the Patriarch of Constantinople or the Russian Orthodox Church, and about 90% of Montenegrin Orthodox believers have remained with the Serbian church instead.[60] After Montenegro passed a controversial freedom of religion law in 2019 that would see properties of religious organisations transferred to the Montenegrin state upon certain conditions, the Russian Orthodox Church was quick to take a political position in the debate, while prominent Serbian clergy organised and led street protests.[61]

Third, the Serbian Orthodox Church supports nationalist and far-right groups and individuals who often advocate for closer ties with Russia. For example, it has twice decorated abovementioned Vojislav Šešelj, and endorsed the viewpoints of groups such as Narodne Patrole. The Church has given tacit support to Milorad Dodik’s secessionist agenda in Bosnia and Herzegovina, with Patriarch Porfirije himself taking part prominently in the banned 9 January Republika Srpska victory parade in 2022.[62] In effect, the Orthodox Church is both a channel for Russian narratives, a tool employed by Russia to sow divisions, and a political actor in itself that supports pro-Russian politicians and Serb nationalism in the three countries.

In conclusion, Russia’s political clout stretches especially to (pro-)Serb politicians, who often make use of similar narratives and use Russia as an external supporter to promote their own ideas. Political relations between Russia and the three countries, unlike those with the EU, remain, however, fragmented and under-institutionalised. While this may be a deliberate strategy, it is determined by the entry points the context offers, which are more limited than in the case of Russia’s more direct neighbours. Of the three countries, entry points for Russian influence are most widespread In Serbia, followed by Bosnia and Herzegovina. Russia has, however, continued to unconditionally support nominally pro-Russian politicians in all three countries, including by directly financing their parties. Especially regarding its position on Kosovo, support for RS leader Milorad Dodik and Orthodox Church links remain important entry points for Russian political influence in the region at large.

Russia’s economic clout – forged through energy links

The EU is unquestionably outperforming Russia as an economic partner to Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Montenegro. Even if Russia seeks to maintain, with difficulty, its economic clout through the energy sector, its invasion of Ukraine has further reduced the country’s economic presence in the three countries. To assess the state of Russia’s economic penetration in the Serbian, Bosnian and Montenegrin economies, we take into account Russia’s past and current bilateral economic agreements with the three countries, the state of their energy relations, Russian investments in the region, and tourism and property links.

Trade

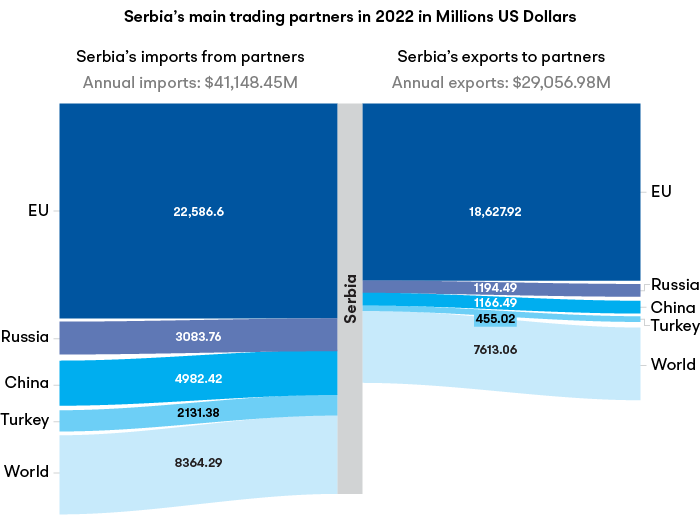

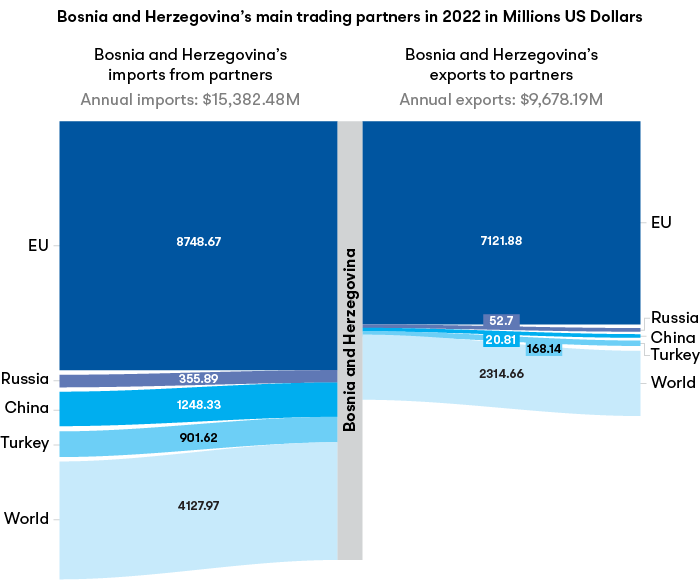

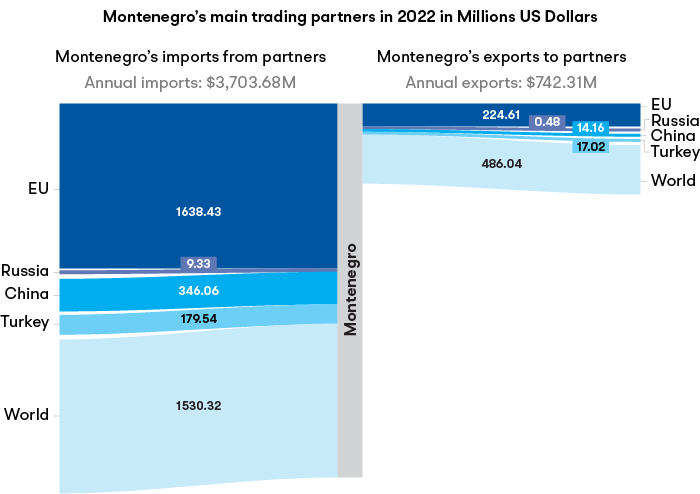

In terms of trade, Russia has sought to involve the three countries in its Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) project, an antipode of the EU’s internal market comprising Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Armenia. These efforts have only led Serbia to sign a free trade agreement (FTA) with the block in 2019, in spite of a Russian commitment to reach a similar agreement with BiH.[63] In the early 2010s, Montenegro was negotiating to extend its FTA with Russia – originally signed in 2000 between the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and Russia – to Belarus and Kazakhstan, the countries with which Russia formed a customs union in 2010.[64] However, Russia stalled the negotiations and the FTA itself in 2014 when Montenegro joined EU sanctions against the country for its annexation of Crimea.[65] By 2022, commercial exchanges between the three countries and the EU had become much more significant than with Russia, as shown in Figure 4. Russia ranks only as the fourth trading partner of the three at large, placed after not only the EU and China, but also Turkey.

Source: IMF Direction of Trade Statistics (DOTS): link

Online interactive graphic

Energy

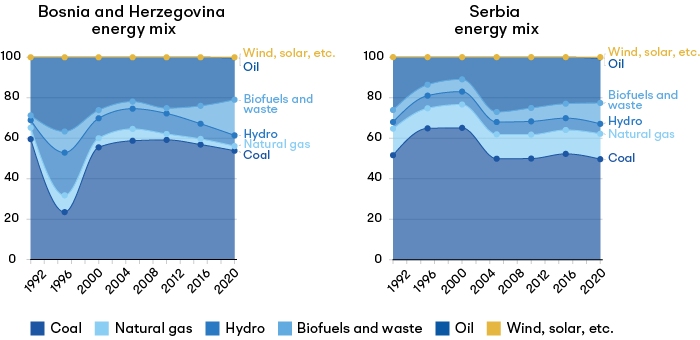

Russia maintains economic clout especially in the energy sector in Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, as it provides nearly 100% of both countries’ gas imports and its energy giant Gazprom owns crucial energy infrastructure in these countries.[66] Russia makes active use of the energy ties to politically influence the region. For example, in May 2022, Belgrade renegotiated with Gazprom a three-year gas contract at favourable prices amidst the war in Ukraine and international sanctions on Russia.[67] For Moscow, it clearly served to support Serbia in withstanding pressure from the EU to join anti-Russian sanctions. It should, however, be noted that the share of gas in each country’s energy mix remains low. In BiH for example, gas constitutes only 3.3% of the country total energy mix (Figure 5).

Sources: International Energy Agency, www.iea.org

Bosnia and Herzegovina energy mix - online interactive gr

a

phics

Serbia energy mix - online interactive graphic

Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina also use energy relations as a political instrument. For instance, in 2008 Gazprom acquired a majority share of 51% in Serbia’s solitary oil company Naftna Industrija Srbije (NIS) for €450 million, whereas experts set the company’s market value at 2.2 billion euros.[68] The transaction, which was brokered by Serbia’s former prime minster Vojislav Koštunica, is believed to have been motivated by a political logic from Serbia to secure Moscow’s support on the Kosovo issue and a guarantee that the now defunct gas pipeline project South Stream would go through Serbian territory. Interestingly, the Serbian government now speaks of Russian energy infrastructure ownership as a barrier for its asserted energy diversification ambitions, even if such diversification is being supported by the EU and US alike and some steps have been taken in that direction.[69] In Republika Srpska (RS), the partly state-owned Russian company NeftGazInkor bought the two main oil refineries – located in Brod and Modriča – in 2007. In subsequent years, the two refineries operated at a loss, totalling €1.3 billion at the end of 2022.[70]

For Russia, economic profit has clearly been subordinated to the excessive gains in political leverage of these investments.[71] However, current EU sanctions against Russia are expected to reduce the country's leverage, as they will prevent Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina from importing Russian gas transported via ports and pipelines in EU member states.[72] In that regard, Serbia will experience the consequences of EU sanctions on Russia even if it did not join them. This may motivate Belgrade to diversify its sources of energy, although the country for now has, like EU member state Hungary, largely continued to import Russian oil and gas.[73]

Investments, real estate, tourism and migration

In the aftermath of Russia's invasion of Crimea and implementation of international sanctions, the Western Balkan countries have experienced a stagnation or even diminution in the proportion of Russian investments relative to the size of their economies.[74] However, Russian investments in Serbia saw a boom, as Russian businesses redirected to Serbia due to the war and the ensuing international sanctions. In 2022, Serbia experienced an unprecedented surge in foreign direct investment (FDI) which surpassed the average FDI inflow of the previous years by €500–600 million. In the same year, Serbia saw the creation of 1,020 Russian businesses – a figure 12 times higher than in 2021 – due to the influx of Russians into the country.[75]

In Montenegro, the same trend can be seen. Despite Montenegro’s status as a non-friendly state and its sanctions against Moscow, the country continues to receive substantial investments from Russian companies and citizens. The Central Bank of Montenegro declared in July 2022 that Russians remained the largest investors in the country, investing more than €41 million after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The most important investments are made in the housing sector, in which Russians are believed to own more than 40% of Montenegrin real estate.[76] Russians invest especially in the Adriatic coastal towns of Bar, Herceg Novi, Petrovac and Budva, as they have sizeable Russian communities. In terms of tourism, according to official Montenegro Statistics Office data, there were more Russian tourists in 2022 than in 2021, but it is unclear whether they comprise only tourists or also people travelling to escape the war.[77]

Within the context of the economy and tourism, it is noteworthy that a considerable number of Russians – estimated at 13,000[78] – have chosen Montenegro as their destination while fleeing their country after the start of the war. Montenegro’s ‘Golden passport’ scheme has contributed to this trend, with 70% of all golden passports being handed to Russian citizens.[79] Wealthy Russians who made a substantial investment in Montenegro (amounting to 450,000 euros) benefitted from this economic measure until, under strong EU pressure, Montenegro ended the programme at the end of 2022.[80] With regard to Russian migration to Serbia, two waves are generally distinguished. The first wave primarily consisted of political dissidents and activists who sought refuge in Serbia. The second wave brought Russians who were more concerned about professional and business interests; this resulted in a surge in Russian-owned companies registered in the country.[81] One Russian refugee who fled the war and founded an organisation called the Russian Democratic Society in Belgrade, lawyer Peter Nikitin, estimates that about 40% of the estimated 220,000 Russians in Serbia fully oppose the war, while 60% would have a more neutral position.[82]

Russia’s influence in the economic sphere is outperformed substantially by that of the EU, especially in terms of trade. Russia’s far-reaching influence in the energy sectors of BiH and Serbia, however, yields substantial political leverage, even if its investments often prove economically inviable. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has led to a redirection of Russian companies to Serbia in particular, with a further boom of Russian investments in the property sector in Montenegro. These developments do not directly provide Moscow with additional political influence.

Russian influence through security and military cooperation: a story coming to an end?

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Moscow’s security involvement in the Western Balkans has toned down but not become insignificant. Due to the region’s history and geographical location – being bordered by EU and NATO member states – and in contrast with the Eastern Partnership countries, Russia has no military presence in the Western Balkans. As such, it must resort to other, hybrid, methods to stir up unresolved conflicts and instability. Nevertheless, Russia still manages to maintain some military and security links with its main allies, Serbia and the Republika Srpska (RS). It does so through military pacts, joint exercises, military training and arms supplies. However, with NATO member Montenegro, such cooperation is wholly absent. Montenegro’s (as well as Albania’s and North Macedonia’s) NATO accession highlights the fact that Russia has in the past few years largely failed to prevent the overall integration of the region with Euro-Atlantic institutions in spite of its obstructive agenda.

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Serbia has continued to hold observer status within the Russian-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), even if in practice contacts have been limited. Serbia has officially proclaimed military neutrality since 2007, but has participated in several ‘Slavic Brotherhood’ joint military exercises and a military initiative involving the Serbian, Russian and Belarusian armed forces.[83] Belgrade displayed some sensitivity to EU pressure when it froze its participation in the 2020 exercises without notifying Minsk beforehand, although it re-joined the exercises from 2021 until the Russian invasion of Ukraine one year later.[84] Factually, even if politically sensitive in the country, NATO is a much more important partner to Belgrade.[85] As a NATO Partnership for Peace (PfP) country, Serbia has undertaken significantly more military exercises with NATO than with Russia.[86] Serbia’s first joint military exercise since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 is the ‘Platinum Wolf’ exercise with NATO.[87] At the same time, Serbia’s Director of the Security Information Agency, Aleksandar Vulin, attended an international security conference in Moscow in May 2023.[88] It is unclear whether the country would be willing to face further pressure from the currently geopolitically awakened EU if any further joint exercises were to be initiated by Russia.

The Russian-Serbian security relation includes arms supplies. Moscow provided Belgrade with air defence systems, anti-tank weapons, drones and other military hardware between 2018 and 2021.[89] These deliveries were part of a military technical assistance agreement signed by both parties in 2016 to support Belgrade in modernising its military. Even as Russia has been Serbia’s most consistent supplier of military equipment since that year, Russia is not the only game in town.[90] According to the SIPRI Arms Transfers Database, in 2022 China exported more arms to Serbia (320TIV) than Russia did between 2016 and 2022 (306TIV).[91] When it comes to arms deliveries, it is furthermore relevant to mention that Serbia itself has, according to leaked US intelligence documents, and in spite of its professed neutrality, exported arms to Ukraine in the past year. This was vehemently denied by Serbia itself at first, although Serbian president Vučić later admitted that Serbian ammunition was possibly sold to Ukraine through intermediaries and that he is not opposed to that.[92]

Russia also cooperates with the Republika Srpska entity in the security domain, specifically regarding counterintelligence, counterterrorism and police training.[93] Western actors are concerned with the militarisation of the RS police as well as the potential construction of another Russian operational (officially ‘humanitarian’) centre, similar to its facility in Niš (Serbia).[94] Sarajevo also claims that RS is trying to procure Russian anti-aircraft missiles. Such arms deliveries could contribute to future tensions and are concerning, as the RS entity also acquired 2,500 automatic rifles from Serbia.[95] RS cooperation with Russia goes against Bosnia’s cooperation with NATO, which has, in spite of resistance and delaying tactics from RS, gradually increased in the past years. The country has had a PfP agreement with NATO since 2006, was offered a Membership Action Plan in 2010, and as part of that effort submitted a so-called Reform Programme in 2019.[96]

To summarise, Russia seeks to maintain its military cooperation with its main partner, Serbia, while also supporting the militarisation of Republika Srpska. Belgrade is satisfied with its current degree of cooperation with Moscow but seeks to avoid becoming Russia’s foothold in the Balkans. In reality, Russia is only one of multiple security actors in the Balkans, overshadowed by NATO and challenged by China.

Russian malign influences: proxy groups, cyber attacks and meddling in internal affairs

While presenting itself as a partner to Serbia and the RS in particular, Russia also resorts to malign actions to influence developments in Serbia, Montenegro, and Bosnia and Herzegovina. It supports non-state paramilitary, criminal and cyber groups in the region, and interferes in political affairs to the scale of supporting political coups. Russia furthermore facilitates direct cyber-attacks from Russia, and Russian private military companies like Wagner recruit citizens to fight for private military cooperations in Ukraine.

Russia employs existing non-state organisations, organised crime groups and hacker societies in the Western Balkans to destabilise the region and further its influence. Moscow does not directly coordinate actions led by such actors, but instead supports their activities in an informal manner and through a multitude of actors such as oligarchs, representatives of the Orthodox Church, or political proxies. At the same time, local malign groups sometimes operate in line with Russian interests while lacking direct engagement with Russia. As such, Moscow is not always engaged, but if so, it is in an indirect manner, making involvement difficult to prove.

Proxy groups

The infamous ‘Night Wolves’ biker group is one of Moscow’s proactive proxy groups, with local chapters in Serbia, Montenegro and BiH. In 2018, Russia allegedly provided the group with a $41,000 grant to tour the Western Balkans and demonstrate in support of Milorad Dodik and his ambition of the ‘peacefully disintegration’ of BiH.[97] ‘Serbian Honour’, another proxy, is a far-right group with links to organised crime active in Serbia and RS and was allegedly established in the ‘Russian-Serb Humanitarian Centre’ in Niš. In 2018, its BiH faction was reported to act as Dodik’s personal security force, but more recently, the group has diminished in importance, seemingly because of earlier overexposure.[98]

For both Serbian Honour and the Night Wolves, it would go too far to label the organisations as ‘paramilitary’, given their lack of a military-like structure. The only proxy group that to a certain extent resembles a military organisation is the 2016 founded ‘Union of Cossacks of the Balkans’.[99] Viktor Zaplatin, one of the prominent Union’s leaders, served in the Soviet army. The Union’s main mission is to promote pro-Russian, conservative and Orthodox narratives and push back on the ‘imposition’ of western values.[100]

Another, recently visible, proxy group is the Serbian group Narodne Patrole, or national patrol, led by Damnjan Knežević, one of the founders of the far-right political party Serbian Oathkeepers. Knežević travelled to the then newly opened Wagner Centre in St Petersburg in November 2022. He was arrested in February 2023 over violent protests in Belgrade against Serbia’s normalisation process with Kosovo but released soon after.[101] The group can be described as ultra-nationalist, anti-migration, and openly pro-Russian and pro-Wagner. It remains unclear to what extent they actively facilitate Wagner activities in Serbia.

In addition to the proxy groups, Russian oligarchs have also set foot in the region. A prime example is Konstantin Malofeev, an oligarch and founder of the Charitable Foundation of St Basil the Great, an organisation that seeks to spread the Russian Orthodox faith, a key asset for reaching out to conservative groups in the Balkans.[102] Malofeev was implicated in the early organisational stages of the 2016 Montenegro coup.[103] Interestingly, Malofeev’s spiritual adviser is the Orthodox priest Bishop Tikhon, who is also Putin’s spiritual adviser. Although not all of these actors are directly coordinated by the Kremlin, many proxy groups, Orthodox brotherhoods, Russian oligarchs and Orthodox figures form a loosely connected network across the Balkans.[104] According to an interviewee, they are organised locally in order to maintain a low profile, but when deemed necessary by Russia, they are quickly united, such as happened in the pro-Russia protest in Belgrade in March 2022.[105]

While explicit public evidence is lacking, support and training of malign groups is believed to take place through the ‘Humanitarian’ Centre in Niš, Serbia. Formally intended for disaster relief, the centre is believed by the West to be an intelligence centre and is suspected of hosting military training for paramilitary units. Vucic’s government has so far refused to grant diplomatic status to the centre’s Russian staff.[106] Rumours surfaced in 2018 about the construction of a similar centre in RS near Banja Luka but are denied by the Russian Embassy in Sarajevo and after 2018 no further reports have been published.[107]

Political and digital interference

Another form of Russian malign actions is meddling in political affairs. The most prominent example is the 2016 political coup attempt in Montenegro as the country was about to join NATO. The coup failed as a result of poor organisation, mainly because Russia relied on a loose web of proxies, including radical Serb nationalists and Night Wolves, but also the earlier-mentioned Democratic Front politicians. Several backed out just days before. Although concerning, the episode shows that Russia is not the strategic mastermind it is sometimes believed to be.[108] In the wake of the failed coup, 13 people, including two Russian intelligence (GRU) officers (in absentia), Eduard Shirokov and Vladimir Popov, were convicted, although a retrial is currently underway.[109] So far, no other coup attempts at such scale have been discovered, although Russian-Serbian relations did take a limited hit over a Russian espionage operation revealed in 2019, in which a retired military officer was seen taking large sums of cash from a Russian diplomat.[110]

Russia also uses cyber-attacks to destabilise the Balkans. Montenegro is the most targeted country in south-east Europe. On the same day of the coup attempt, the Montenegrin authorities were struck by cyber-attacks. Attacks were attributed to the APT28 group, also known as Fancy Bear, which is claimed by the US to be tied to the Russian intelligence organisation, GRU.[111] It is of some concern that Montenegro has the second-lowest regional score on the Global Cybersecurity Index, while Bosnia and Herzegovina scores lowest.[112] In August 2022, Montenegro’s government websites and critical infrastructure systems were targeted by largescale cyber-attacks. Despite Cuba ransomware – a Russian-speaking gang – claiming responsibility for part of the attack, the Montenegrin National Security Agency blamed the attack on Russia, stating that some organisations are a disguise to hide Russian government involvement.[113]

Private military corporations

Lastly, amidst the war in Ukraine, signals regarding the recruitment of Serb and Bosnian nationals to join Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have also come to the fore. It is estimated that a few dozen Serb nationals are currently fighting alongside Russian forces in Ukraine, meaning numbers are not substantial.[114] Recruitment to the Wagner group has been facilitated by veterans organisations, such as those from the RS capital, Banja Luka (affiliated to Serbian Honour), which retain close links with Russian counterparts.[115] Serbian Cossack groups are also believed to be a tool of Russian influence in the region, and are also potential sources of recruits.[116] The most visible recruitment effort was perhaps in early 2023, when Russia Today’s Balkans service published a Wagner advertorial to join the private military company in Ukraine.[117] Wagner murals also appeared in Serbia and North Kosovo.[118] The Serbian central government firmly condemned Wagner’s mercenary activities in the country.[119]

To conclude, Russia resorts to malign instruments which have often proven to be effective in shaping the political environment of the Western Balkans. Lacking a military presence in the region, Russia supports far-right nationalist figures and organisations, which generally better resemble organised crime groups than paramilitary organisations, to attain its goal of destabilisation by stirring up polarisation and anti-Western sentiment. Although such malign influence has not succeeded in distancing the Balkan countries from their rapprochement with the West, Russia has allowed malign actors to become more active in the region to the point of destabilising entire governments.

Media and disinformation as successful tools to spread Russian narratives

Russia’s influence in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro and Serbia may be most visible through its ability to promote its narratives and spread disinformation via (social) media. Such influence runs through Russian media active in those countries, penetration of Russian narratives in local media, and Russian disinformation campaigns via social media.

In recent years, Russia has increased its involvement in the Balkans media sphere using local outlets as a means to disseminate pro-Russian narratives and foster anti-Western sentiment. Two prominent tools employed are the Serbia-based propaganda giants RT Balkan and Sputnik, which publish content in the Serbian language.[120] The US Department of State’s Global Engagement Centre holds that these media organisations use ‘the guise of conventional international media outlets to provide disinformation and propaganda support for the Kremlin’s foreign policy objectives’. This perception is supported not only by the propagandist content, but also by the fact that journalists working for Sputnik Srbija are paid directly by Moscow.[121] RT Balkan is expected to launch a television channel by 2024.[122] Although RT and Sputnik only have offices in Serbia, the propagation of fake news, disinformation and Russian propaganda has spilled over into Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro, facilitated by the similarity of the languages. Sputnik is working closely with media outlets in Republika Srpska, which publish news in the Serbian language such as the TV station RTRS, the news agency Srna and the station ATV, providing a platform for RS president Dodik which he has used to spread secessionist calls.[123]

Russian media’s lack of restrictions on access to content is a meaningful aspect of their influence on local media. Given structural underfunding issues that media in the region cope with, Russian portals provide content free of charge, which in turn, allows local media to republish information sourced directly from Sputnik and RT, who thereby uncritically replicate Russian narratives.[124] Although the direct reach of RT Balkans and Sputnik is limited, they do have an effect on the wider media landscape. For example, various tabloids had no problem with publishing headlines that read ‘Ukraine attacked Russia’ or ‘America is pushing the world into chaos’ when Russia invaded Ukraine.[125]

Russian narratives’ in local media, apart from the cited Russian channels, has mostly come about as a result of local initiatives rather than direct Russian involvement.[126] As a systemic trend in Serbia and Republika Srpska in particular, media outlets are strongly influenced by political forces that support pro-Russian discourses.[127] For example, the Serbian public broadcaster RTS owns popular TV channels which attract up to a quarter of the Serbian audience and effectively convey pro-government messages.[128] Other, private TV stations, notably TV Pink, also spread pro-government messages and are closely connected to the Serbian government. Apart from TV, daily newspapers like Politika and tabloids like Informer spread pro-Russian narratives in Serbia.[129]

Russian narratives easily penetrate the collective unconscious especially as the media literacy level in the region is relatively low.[130] Pro-Russian views in the three countries do not come solely from media reporting – they build on existing supportive sentiments towards Russia in parts of the societies, arising from historical ties, shared conservative values, statements by politicians, and other factors. Nevertheless, there is a correlation between the presence of pro-Russian narratives in the media and popular beliefs in the three countries examined in this study.

A survey conducted by the European Council on Foreign Relations in summer 2021 revealed that 54% of Serbians regarded Russia as an ally, while another 41% viewed it as a necessary partner.[131] In the wake of Russia's invasion of Ukraine, Serbian attitudes towards Russia exhibited only minimal change. A mid-2022 poll reported that, even in the midst of the conflict in Ukraine, 51% of Serbs consider Russia their most crucial partner, 66% regard Moscow as their country’s ‘greatest friend’ and 61% of Serbs hold the West accountable for the outbreak of the war.[132] In Republika Srpska, 52% support Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. Even in Montenegro, a NATO member, 37% of those polled admitted having a positive opinion of Vladimir Putin.[133] Russian disinformation is also increasingly pervasive in the social media sphere. For example, in July 2022, amidst escalating tensions between Kosovo and Serbia, Russians and pro-Russian Telegram channels were spreading false information about the situation in the Russian and Serbian languages – information that was eventually denied by the Serbian and Kosovar authorities.[134] Also, a ‘troll farm’ suspected to be active during the 2016 US presidential elections was active in spreading disinformation during the 2018 Macedonian referendum on the name change of the country.[135] Russian embassies in the region have also been employing social media for disinformation purposes, seeking to attract support for the country’s policies.[136]

Some online disinformation originates from the region itself. In 2020, Twitter shut down 8,558 bot accounts linked to the Serbian Progressive Party that fuelled social media with news promoting the Serbian government and attacking opponents.[137] In recent years, the popularity of digital media has grown swiftly in the region, even if television has remained the most consumed type of media.[138] As such, as the least regulated media market in the region, the internet has become an important arena for disinformation.[139]

In summary, Russian propaganda penetrates Serbia, Montenegro, and Bosnia and Herzegovina through Russian-funded portals, local media and social media. The impact of Russian media in the Western Balkans cannot be overstated, as local and European news outlets constitute a notable proportion of the region’s media realm.[140] Nevertheless, Russian disinformation and narratives have penetrated the region to such an extent that considerable sections of society hold a positive image of Russia and its political leadership.[141]

See: Vuk Vuksanović, “Russia in the Balkans: Interests and Instruments,” Europe and Russia on the Balkan Front: Geopolitics and Diplomacy in the EU’s Backyard, Istituto per gli Studi di Politica Internazionale, March 2023, 39.