A number of commentators fielded the view that the May 2018 election and its aftermath disrupted Iraq’s sectarian discourse and its power-sharing mechanisms based on the Al-Muhasasa principle.[39] Their argument was based largely on the inability of Iraq’s Shi’a and Kurdish political elites to unite in electoral lists or post-election coalitions within their communities as was characteristic of previous elections (2005, 2010 and 2014),[40] in order to subsequently negotiate a predominantly Shi’a-Kurdish government. Instead, Iraq’s Shi’a parties split into at least five main blocks under, respectively, Al-Sadr, Al-Abadi, Al-Hakim, Al-Maliki and Al-Ameri. The Kurdish elites, in the form of the Barzani’s and Talabani’s (KDP and PUK), could not unite either. This section briefly describes the 2018 elections with a view to analysing factors of change and continuity from a sectarian point of view. It acquires extra salience from the fact that Iraq may soon be heading to the polls again if the country’s new Prime Minister Al-Kadhimi honours his promise.[41]

Part of the explanation for the 2018 lack of Shi’a and Kurdish electoral unity can be found in the radical changes that transformed Iraq’s security and political landscape between 2014 and 2018: a) the rise and defeat of the IS, which delegitimised Al-Maliki and strengthened Al-Abadi, splitting their Da’awa party in the process; b) the increase in strength of political parties linked with Al-Hashd al-Sha’abi groups tied to Iran, which created a new Shi’a network of power; and c) the 2017 referendum on Kurdish independence, which created significant distrust within the Kurdish political elites (see also Annex 1).

Electoral strategies and voter choices also played a role in preventing Shi’a unification for electoral purposes. Al-Abadi’s, and to a lesser extent Al-Ameri’s, electoral strategies used nationalist rhetoric and pursued a more issue-based approach to politics. Their approach de-emphasised sectarianism but did not challenge the bases of sectarian rule in Iraq. In contrast, Al-Sadr and his Sairoun list used the grievances of Iraq’s protest movement to advance a reformist agenda centreed on the demands of disfranchised citizens.[42] This was essentially an anti-elite agenda. Popular disappointment in the ruling political leadership (Al-Abadi in particular) and a low voter turnout marginally favoured Al-Sadr whose agenda was, however, difficult to reconcile with the prevailing political system.[43] This made achieving Shi’a unity more difficult.

During the 2018 elections, Haider al-Abadi adopted a nationalist and performance-oriented strategy in a bid to attract voters who might otherwise vote along sectarian lines. Because his Al-Nasir coalition built its campaign around Al-Abadi’s personality and the defeat of IS, his nationalist agenda lacked meaning and narrative compared with more populist/sectarian campaigns. The lack of achievements-in-office beyond the defeat of IS also reduced the credibility of his nationalist performance-oriented narrative.

This lack of ‘other results’ was in large part due to the fact that Al-Abadi did not have a significant political base of his own. This reduced his ability to exercise power effectively, strengthen state institutions and initiate durable reform. Most important has been his failure to address corruption. Despite a grand campaign and unequivocal support from Grand Ayatollah al-Sistani (who exhorted him ‘to strike corrupt officials with an iron fist’), Al-Abadi’s lack of a stable political base and his inability to confront corrupt officials associated with armed groups meant he produced negligible results. His tense relationship with the Al-Hashd al-Sha’bi, Iran and his perceived association with the United States also had a negative effect on his political future. Finally, his inability to resolve the Kurdish issue peacefully followed by an aggressive – although legitimate – response to the Kurdish referendum soured his relationship with Erbil’s political elites.

In short, it is difficult to translate more nationalist and performance-oriented agendas into political power because existing power bases, including substantial voter constituencies, are organised on a sectarian basis. Although Al-Allawi won the 2010 elections with a cross-sectarian list and message, this did not translate into political power. Al-Abadi faced a similar difficulty in 2018, the difference being that his coalition came only third. These examples highlight that the resilience of sectarianism in Iraq lies less in the country’s political discourse – sectarianism has been toneddown across the political spectrum – and more in existing mechanisms of political organisation and vested interests.

Source: Al-Sumaria, 7 August 2015, online (Arabic); Middle East Online, 19 August 2018, online (Arabic); Hadad, H., Iraq’s weak political party syndrome, 1001 Iraqi Thoughts, 27 March 2019, online.

Allegations of election fraud sowed further disunity within both the Shi’a and Kurdish political elites because any changes in the results of the closely fought elections represented a zero-sum game. It therefore came as no surprise that, even after a manual recount of some of the election results and the annulment of the votes of internally displaced people, diaspora voters and Kurdish security forces,[44] the results remained largely unchanged. They were ratified on 19 August 2018.[45] The top contenders were Al-Sadr’s Sairoun coalition with 54 seats, Al-Ameri's Fatah alliance with 47 seats, and al-Abadi's Al-Nasr alliance with 42 seats. No list obtained a clear parliamentary majority.

Once the fraud allegations were settled, the debate on which faction commanded the largest bloc of parliamentarians reignited. The Iraqi constitution confers the right to name the Prime Minister and form a government upon the largest bloc.[46] A problematic aspect of this arrangement is that ambiguity exists about whether parliamentarians (individually and in groups) can switch allegiances after the elections, or whether they are subject to factional discipline and remain bound by their pre-electoral engagements in the post-election period. In the event of the 2018 elections, this ambiguity was not resolved,[47] creating space for co-optation and bribery as well as producing a generally febrile atmosphere in which parties and individuals offered political allegiance in return for posts and influence. As the Shi’a parties were unable to form a coalition bloc, intense competition unfolded between Al-Sadr as ‘reformist champion’ and Al-Maliki as ‘conservative champion’. Al-Sadr was initially able to secure an alliance with Al-Hakim, Allawi and Al-Abadi to form the largest bloc (the Reconstruction and Reform Coalition – Islah).[48] Al-Sadr even managed to gain allegiance from Al-Ameri's Fatah alliance to create a solid parliamentary majority.[49]

At risk of drawing the short straw, Al-Maliki engaged in a bout of clever divide-and-conquer politics. He first created a rift between Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq’s leader Al-Khazali (part of the Fatah coalition) and Al-Ameri (leader of the Fatah alliance), which forced the latter to break off his engagement with Al-Sadr to keep the Fatah alliance intact. Furthermore, Al-Maliki and Al-Ameri convinced Al-Fayadh to break off from Al-Abadi’s Nasr coalition (he served under Al-Abadi as National Security Council chair) in exchange for the position of Minister of the Interior (the nomination later failed). By engineering both splits, Al-Maliki created an opposing bloc to Islah – called Bina – that prevented Al-Sadr from claiming to lead the largest parliamentary bloc.

Interestingly, the arithmetic of this acrimonious intra-Shi’a lobbying, and counter-lobbying, was not disrupted from the outside as Sunni and Kurdish parliamentarians were unable to maintain internal discipline and, for reasons of their own, split between the Islah and Bina blocs. Sunni leaders Allawi and Al-Nujaifi chose to join Islah, while the Sunni Al-Khanjar-Karboli alliance joined Bina – to everyone’s surprise, given the historical enmity between Al-Khanjar and Maliki. In similar vein, Barzani surprised the Iraqi political establishment by joining Bina in a bid to restore his relations with influential leaders in Baghdad and Iran after the 2017 referendum, despite Kurdish animosity towards both Al-Maliki and the PMF. The PUK chose to work with the rival Islah in an effort to maintain its claim on the Iraqi presidency (see Annex 3 for greater detail on these politicians, parties and coalitions).

During this sustained period of politicking, summer protests erupted in Basra and other southern provinces. An escalating series of incidents – which included the torching of party offices (including those of Hashd groups) and government buildings and the breaching of the Iranian consulate – focused minds in Baghdad to break the deadlock and form a government.[50] Still unable to settle the question of which bloc was biggest, Al-Sadr (leading the Islah bloc) and Al-Ameri (leading the Bina bloc with Al-Maliki behind the scenes) reached an agreement to share government positions equally. After taking account of their respective red lines (Bina refused the return of Al-Abadi as Prime Minister, preferring an experienced politician voted in by a majority of parliamentarians;[51] Islah refused a Bina nominee, favouring an independent or technocratic Prime Minister), the blocs agreed on Adel Abdul-Mahdi, an experienced independent politician with a relatively neutral status.[52] Reflecting on these developments allows a few conclusions about the 2018 parliamentary elections to be drawn:

The Al-Muhasasa system remains alive and well. It served as the basis for the Sairoon (leading Islah) and Fatah (leading Bina) coalitions to negotiate the new Iraqi government. Paradoxically, the fact that neither intra-Shi’a nor intra-Kurdish unity could be achieved may have made the system more durable by enabling many parties to claim a slice of power despite a drop in their negotiating power due to greater fragmentation. On the upside, the new cabinet includes some experienced technocratic ministers, such as Mohammed al-Hakim (foreign affairs) and Luay al-Khateeb (electricity).This has less to do with the system itself, however, and more to do with Al-Sadr relinquishing his claim to his share of ministerial posts. Notably, he did not relinquish his claim to his share of sub-ministerial, general director or provincial posts.[53]

The fragmentation of political elites during the process to form a government after the 2018 election, combined with the practices of Al-Muhasasa, further reduced the space available for women and young people. During the elections, female candidates were subjected to more extortion and threats than their male counterparts. Some had their reputation tainted, which forced them to withdraw. Political parties used youth issues and representatives mostly to look good on the campaign trail and the quota of parliamentary seats allocated to women to win additional seats. Once in government, they paid little attention to supporting women’s and young people’s participation and, when forming his cabinet, Abdul-Mahdi did little to involve women or youth.[54] Although Abdul Mahdi recently appointed Hanan al-Fatlawi as adviser on ‘women affairs’, she is seen among women's rights organisations as yet another member of the political establishment.[55]

The government formation process resulted in yet another weak Prime Minister (following on from Al-Jafari in 2005, Al-Maliki in 2006 and Al-Abadi in 2014) in the sense that Abdul-Mahdi lacked a strong political base of his own and was dependent on a wide range of political parties for his position and policies. As a result, the person in charge of governing lacked the political capital to steer decisions through Iraq’s minefield of vested interests. The recent appointment of Mustafa al-Kadhimi as prime minister reconfirmed rather than changed this logic given the fact that he similarly lacks a political power base of his own.[56]

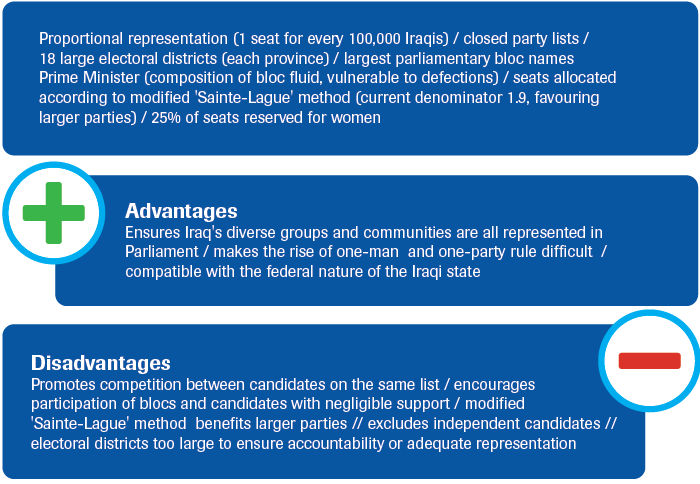

The post-electoral period highlighted the fragmentation of Iraq’s political party landscape, the lack of party discipline within parties and factions, and the inability of coalition and alliance leaders to control ‘their’ parliamentarians. In part, these features are rooted in Iraq’s socio-ethnic diversity, which tends to generate a high number of parties for representative purposes. Until truly national parties develop, this factor will persist. These features also result from elements of Iraq’s electoral law,[57] which reduce inclusion (stimulating party proliferation) and accountability (making it easy to create parties as vehicles for personal advancement) (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1 above reflects the current (‘old’) Iraqi electoral law as the new one remains in the making. See footnote 57 for a short overview of the main differences.

Source: Iraq’s electoral law, Musawy, L. Electoral reform: What’s really needed in Iraq, Washington DC: The Washington Institute, 2018; Al-Rikabi, H., Reforming the Electoral System in Iraq, Baghdad: Al-Bayan Center, 2017.

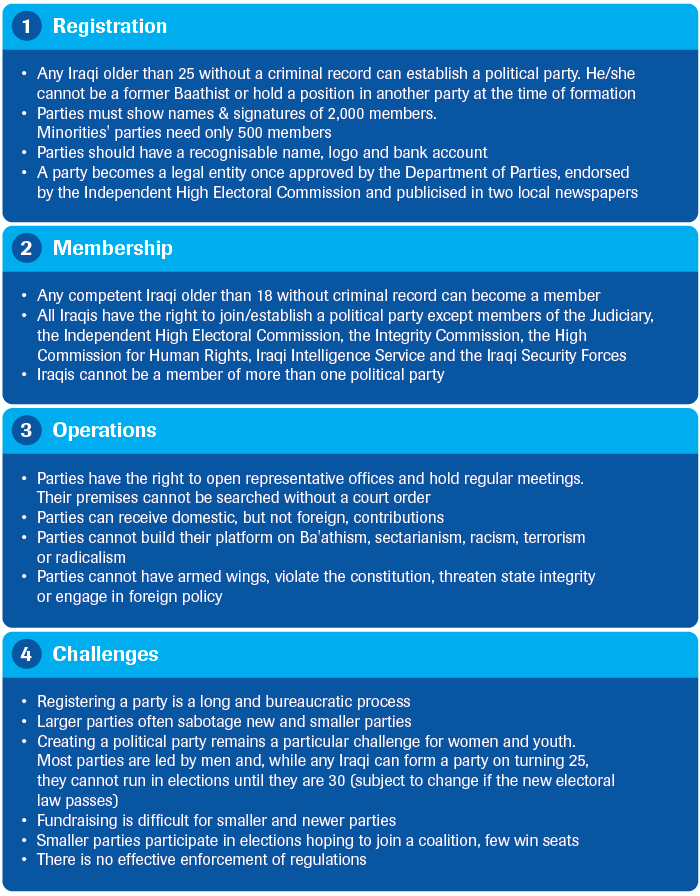

Some commentators have concentrated on the various adaptations of Iraq’s use of the Sainte-Lague method (its ‘divisor’ in particular)[58] for translating votes into parliamentary seats during its 2014, 2018 and 2020 (forthcoming provincial) elections as a key factor influencing political party fragmentation. Such a focus is, however, partial since this votes-to-seats distribution method is only one of the elements influencing fragmentation. Other factors include the ease/difficulty of setting up a new political party (see Figure 2 below), district size, the lack of clarity on the rules for forming and claiming the largest ‘bloc’, and the use of a seat threshold (currently nominal).[59]

The post-electoral period has also shown that, when Iraq’s political elites face threats from outside the system (such as IS in 2014 and widespread protest in 2018), they are able to identify short-term solutions rapidly and pragmatically to complex political power plays. In contrast, solving longer-term policy problems fundamentally challenges the system. Its tortuous decision-making processes, large number of players, politicised judiciary and corrupt bureaucracy form major barriers to developing policy.[60]

On a final note, modifying the rules of Iraq’s political game via constitutional reform is difficult. While the Constitution allows for amendments (Articles 126 and 142), these need to be approved by national referendum, which is expensive, slow and uncertain.[61] A majority of Iraqis would need to agree and no more than three provinces must vote against the proposed changes.[62]

Source: Iraqi Law for Political Parties: link, adopted on 17 September 2015.