Lost in transition: Where might Iran be heading?

Lost in transition: Where might Iran be heading?

By Hamidreza Azizi and Erwin van Veen

Triggered by the death in police custody of a young woman, Mahsa Amini, Iran’s 2022 anti-government protests shook the country and reverberated across the world. There is barely anyone today who has not heard her name, or who does not know about the nationwide protests in Iran. As videos went viral of young men and women protesting en masse and of the evermore brutal crackdown by security forces, one thing became clear: Something fundamental has changed in Iran. But what is it, exactly?

As with all the smaller and larger protests of the last four decades, the Islamic Republic has managed to emerge unscathed from the most recent ones by means of the targeted application of violence. Methods ranged from direct fire to mass arrests, torture, forced confessions and executions. But suppressing the problem does not mean solving it. Sociologists and political scientists, some of whom are based inside the country, warn that the root causes of the recent protests remain and can re-ignite in response to just another spark. They include widespread public dissatisfaction with the lack of political and social freedoms, growing authoritarianism, economic mismanagement and systemic corruption. Each new protest episode is likely to pose a more significant challenge to Iran’s political system and its ruling elites. The failure of pro-reform political factions to bring meaningful change about over the past forty years has also radicalized public demands. Demands for change of the system have replaced demands for change within the system.

The 2022 protests reflect decades of accumulated social and political grievances. Iran has witnessed big protest movements before, such as those of 2009 and 2019[EvV|C1] . Yet, this has been the first time that the call to overthrow the Islamic Republic has become the public’s main demand. More importantly, it united Iranians across economic classes, geographical locations, and ethnic groups. It is for these reasons that the recent protests represent a turning point. They make restoration of the status quo from before September 2022 hardly conceivable. Instead, they can be viewed as the starting shot of a transitional process for Iranian society and politics.

What we mean by transition is not necessarily a journey towards democracy. Instead, we refer to transition in the general sense: “a change or shift from one state, subject, place, etc., to another”, or “a period or phase in which such a change or shift is happening.” Its outcomes are uncertain, but its evolution can be tracked and monitored. We will use four key indicators in this blog over the next 12 months to assess where Iran might be heading: 1) state-society relations, 2) intra-elite dynamics, 3) economic prospects, and 4) foreign relations.

State-society relations

By ‘state-society relations’ we refer to the dialectic between protests, their demands and organization, as well as societal trust/distrust of the government on the one hand, and repression, co-optation, intimidation and reform by the state on the other. Otherwise put, the tension between the discourse and reality of popular protests and counter-claims by state representatives. Following long weeks of protests in late 2022 and early 2023, methods of claim-making shifted from the street to civil disobedience and social media activism. Nationwide strikes - a form of civil disobedience - could not be maintained due to the severity of Iran’s economic crisis (with a few exceptions). They are simply unaffordable for most people. But women’s non-compliance with the state-dictated dress code of a mandatory hijab has continued and is much more successful. Moreover, experts such as Mehrdad Arabestani, professor of anthropology at the University of Tehran, argue that the decrease in street protests is not a sign that people’s anger toward the government is subsiding, but rather that their anger has been suppressed. For the moment, protests remain largely spontaneous and leaderless despite various efforts inside and outside Iran to form a coherent and inclusive opposition.

''Cosmetic reforms and consolidation of authoritarianism is the name of the game.''

On the part of the state, initially direct means of repression, intimidation, and control prevailed. By the end of 2022, as many as 507 people were killed during the protests. In the same period, over 18,500 people, including at least 665 students, were reportedly arrested. Iran’s judiciary also sentenced a number of protesters to death on the charge of waging “war against God,” at least two of whom were executed. By mid-January 2023, the government had shifted to a combination of direct and indirect means, especially by projecting a more conciliatory image of itself. It started by claiming that it managed to “put an end to the riots”. With the approval of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei, this allowed the judiciary to announce pardons for “tens of thousands” of those arrested during the protests. But the terms of this “general amnesty” were less generous than what meets the eye. On the one hand, those arrested had to sign a written commitment that they would not participate in anti-government protests in the future, or else an even heavier punishment would await them. On the other hand, many of those granted amnesty had done nothing more than participate in peaceful protests and should not have been arrested in the first place. Moreover, many famous political figures and journalists remain imprisoned, social media remain blocked and the Iranian parliament has been working on plans to further restrict internet access. The parliament also intends to criminalize any critical comment about the state of affairs in the country with penalties running up to 10-15 years in prison. Cosmetic reforms and consolidation of authoritarianism is the name of the game.

Putting the elements outlined above together, it becomes clear that even though societal dissatisfaction and impatience grow, Iran’s ruling elites have no intention of making even symbolic concessions, let alone engage in reform. This points to a fundamental rupture between a large part of the population and its ruling elites. Instead of the state seeking to reforge Iran’s social contract over the months ahead, for example by initiating political discussion about limited changes or increasing relief and welfare, it will punish resistance more severely. This will present many Iranians with a stark choice: submit or revolt. Given Iran’s poor economic situation, a mix of these two is likely with the revolutionary component getting stronger but going underground.

Intra-elite dynamics

Speaking of intra-elite dynamics, a distinction should be made between the Islamic Republic’s current elite (those in power today) and its old elite (those in power in the past who have gradually been expelled from decision-making circles over the past two decades. At the height of the protests, leaked reports indicated doubts and disagreements among the current elite on how to deal with protesters. Specifically, Khamenei was reported to have encouraged the police forces “not to lose themselves.” He also criticized the silence of some Expediency Council members and their reluctance to support the government in public. However, those disagreements did not split the current elite or invite any large-scale defections among the security forces. Instead, Iran’s current elite seems to have cohered as the government regained control of the streets. Even those who remained silent during the protests are now speaking out in support of the government.

But the 2022 protests did lead to a decisive break between the Islamic Republic’s old and new elites. For example, Mir-Hossein Mousavi recently issued a statement in which he publicly called for changes to the constitution and the political system. As former prime minister and leader of the 2009 Green Movement, he represent the ‘old elite’ and has in fact been under house arrest since 2011. Nevertheless, his recent statement was the first time in all these years that Mousavi acknowledged the impossibility of reforms within the system. He clearly admitted that reforming the existing system, which was the focus of his past efforts, are no longer possible. Similarly, Seyyed Mohammad Khatami, a former reformist president and also a member of the ‘old elite’, publicly criticized the absence of reforms and the fact that they become increasingly difficult to undertake.

Both statements, especially Mousavi’s, received considerable support from political activists in the country and abroad. The frustration of people like Mousavi and Khatami with the Islamic Republic’s resilience against reform indicates that the country’s political system is increasingly supported only by the ultra-conservative/hardline factions of the elite. This can easily trigger a vicious spiral of a more exclusive and authoritarian style of governance that alienates even more people in the near future.

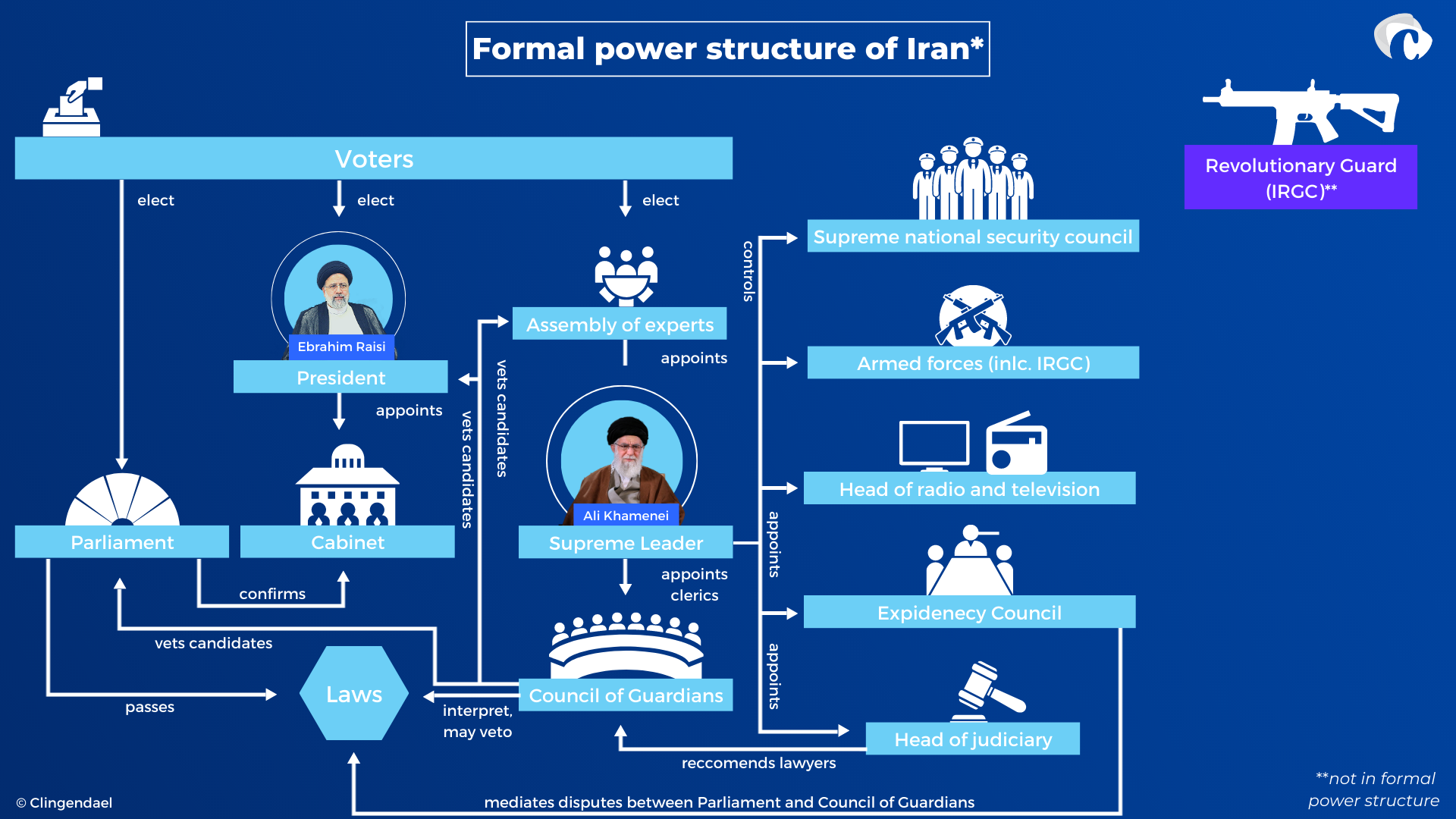

This visual is based on a Reuters graphic.

Economic prospects

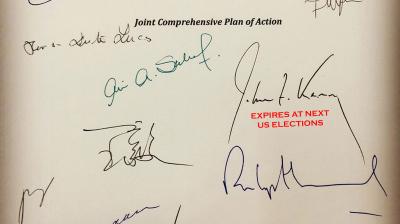

Economic prospects have worsened due to systemic corruption, administrative inefficiency and the failure to revive the 2015 nuclear deal (JCPOA) that has caused economic sanctions against Iran to continue. According to official statistics, the annual inflation rate reached 41.4 percent in February 2023, causing a significant decrease in people’s purchasing power. It is predicted that the purchasing power of Iranians will decrease by at least another 30% in the next Iranian year, which begins on March 21, since the inflation rate is expected to exceed 50%. Iran’s economic growth rate in 2022 was 2.9%, indicating a 3.7% decrease since 2020. Growing poverty and the erosion of the middle class are the direct outcomes of this trend. Economic experts in Iran warn that these conditions are likely to lay the ground for new and even larger protests, which will probably be more difficult to contain. Ahmad Tavakkoli, a member of Iran’s Expediency Council, has warned that if the economic situation deteriorates further, the poor will revolt and “upend everything.” In other words, the prospects for a “rebellion of the poor” is growing.

''Economic experts in Iran warn that these conditions are likely to lay the ground for new and even larger protests, which will probably be more difficult to contain.''

Foreign relations

Last but not least, Iran’s transitional state has also affected its foreign relations. Tehran’s relations with the US, Canada, and the European Union had already become strained over the nuclear issue as well as Iran’s support for Russia in its war against Ukraine before protests started in the fall of 2022. Diplomatic talks to revive the JCPOA reached a dead end in mid-2022 over Iran’s request to receive “guarantees” that a future US administration would not reimpose sanctions. Tehran also demanded that the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ (IRGC) designation as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) by the US be revoked. At the same time, reports of Russia’s use of Iran-made drones against Ukraine began to appear. When challenged, the Islamic Republic claimed that it maintains a neutral stance in the war in Ukraine and has not provided Russia with drones “for use in the Ukraine war.” In this atmosphere, the West’s indirect support for the protests in Iran, i.e. in the form of political discourse condemning repression and additional sanctions, increased tensions further. Moreover, the European Union and United Kingdom have debated the potential designation of the IRGC as a terrorist organization. These actors, along with the US, no longer view restoration of the JCPOA as priority.

As relations with the West evolve from poor to worse, the Islamic Republic increasingly orients its foreign policy eastwards, particularly to Russia and China. After becoming a full member in the Russian and Chinese-led Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), Tehran has sought to deepen relations with Beijing and Moscow in various bilateral and multilateral frameworks. Beyond their newfound military cooperation, Iran and Russia have also reached agreements to expand economic cooperation. However, considering that both countries are under the severe sanction regimes and feature similar economic structures, there are doubts about the likely success of such agreements. Iran’s government has also reached out to Beijing to secure an economic lifeline in the face of sanctions, but its own domestic instability will likely limit Chinese economic engagement. Practically, this means that the substantial investment, to which both countries agreed under their 25-year Comprehensive Strategic Agreement of 2021, will suffer delay or will not be implemented.

Conclusion

The review of these four indicators of the state of Iran’s transition makes clear that the country’s newfound stability is fragile and barely sustainable, at least not in its current form. The gap between what society demands and what ruling elites are willing to compromise make reconciliation impossible. The near-term could well see high-ranking defections from among the old elite, but this will only have a limited impact on the security forces and the administration. It would, however, further erode what remains of the regime’s popular legitimacy. Moreover, difficult economic conditions have put attainment of a decent life out of reach for many Iranians and this increases the potential of economically-motivated protests by the poor and unemployed. At the same time, Iran is more distant from the West than ever and likely to be disappointed in its expectation of rescue from the East, at least in economic terms.

This is the first edition in a Clingendael blog series called Iran in transition: The Islamic Republic is no more while it lives on. In the next blog, we explore in more detail how Tehran’s foreign policy influences the state of transition and what its domestic ramifications are likely to be.

Stay tuned for the next blog. Subscribe to our Middle East Updates.