News

The Clingendael Academy helps diverse professionals to improve their negotiation skills. Diplomats, mediators, military officers and aid workers in conflict situations. At its core, the work of these professionals shares many similarities, but each group emphasises different elements in the negotiation process. Leela Koenig and Evelien Borgman train negotiators from humanitarian organisations. We asked them how a humanitarian negotiation works and what interests are involved.

What is humanitarian negotiation actually?

In general terms, humanitarian organisations and their staff negotiate to carry out an activity or gain access, Borgman and Koenig explain. This often involves providing humanitarian assistance and protection in conflict areas or places where natural disasters have occurred. "This includes offering protection or shelter to displaced individuals, for example.'' Negotiations take place at various levels and with different parties. You have individuals who engage in discussions with armed groups controlling an area on the front line. Simultaneously, negotiations are conducted at headquarters with authorities." Additionally, various humanitarian organisations engage in dialogue with each other regarding a joint approach.

Borgman and Koenig identify the three main pillars in humanitarian negotiation.

#1: The Humanitarian Principles and law

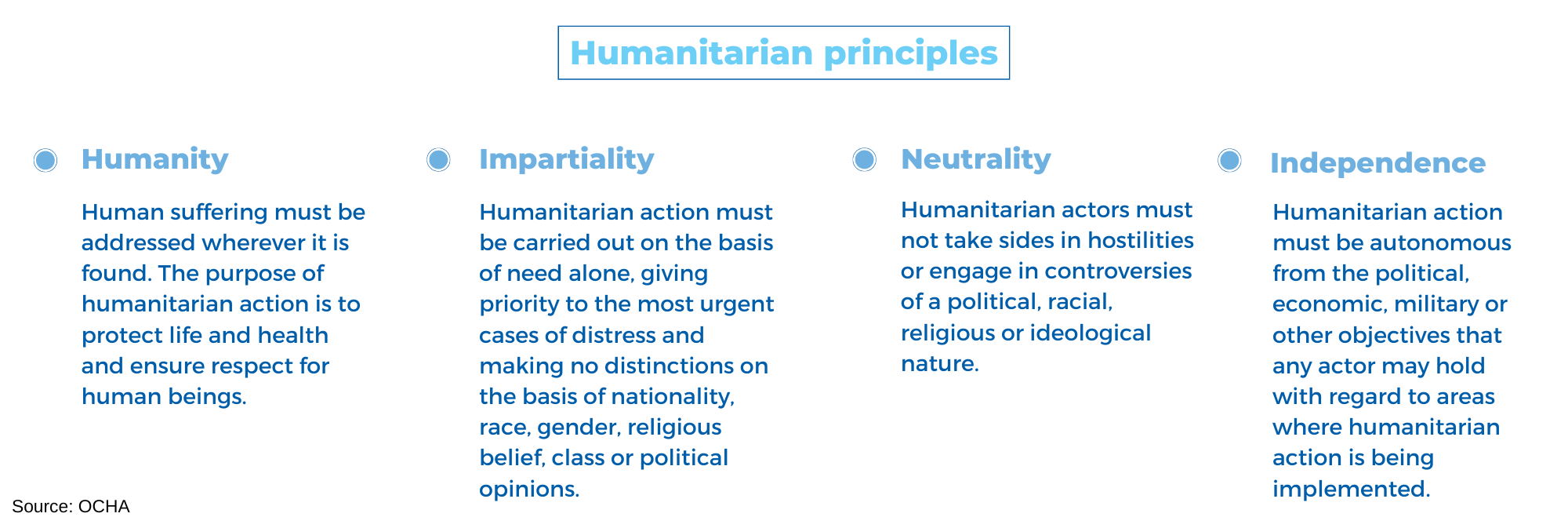

What plays a huge role in humanitarian negotiation is international humanitarian law (IHL, ‘the law of armed conflict') and the principles of humanity, impartiality, neutrality, and independence (see figure below). These principles form the foundation for humanitarian actions. They help set boundaries for what can be agreed upon. "It shouldn't matter where someone in need of aid comes from; whether that person is on the side of the government or the opposition. However, the reality is more complex. Parties who control a certain area sometimes say, 'We only want our own people to be helped.' That presents a significant challenge: negotiating the conditions under which humanitarians can provide assistance while keeping the principles in mind." These are the types of challenges that participants are trained for at Clingendael. You formulate your mandate for a negotiation and adapt it to a specific situation, taking into account the humanitarian principles. You must ensure that you safeguard the red lines of your organisation and preferably the entire sector. "And what if you cannot help certain individuals due to those red lines? What if an armed militia disregards your principles? Humanitarian negotiators are constantly confronted with such dilemmas and questions."

#2: Collaboration

During a humanitarian operation, many organisations can be involved, including major intergovernmental parties like the UN, as well as local NGOs. For effective collaboration, the UN has a coordination system with consultative bodies at various levels. ''The consultation in these systems is often a negotiation in itself,'' the trainers describe. Organisations have different roles and interests. There are sometimes different interpretations of the four core humanitarian principles and what they mean for the situation at hand. "Imagine you have five organisations in an area and you're denied access to a specific region. Then it helps when you collectively determine what the priorities and red lines are. Ideally, you then send one person forward to negotiate access. However, concessions are inevitable before reaching that point."

Some want to move away from the practice of predominantly large international organisations flying in staff to solve the problems.

#3: Safety

Safety is perhaps the aspect that distinguishes humanitarian negotiation the most from diplomatic or political negotiation. Aid workers operating in the field often work in areas with armed conflicts. In extreme cases, they may need to be evacuated, but then the civilians are left behind. Local staff will stay as well. Aid workers may face threats and intimidation, for example, when militias fail to distinguish between their enemies and aid workers. "Local staff do not always have support from a large headquarters, even though the importance of localisation is increasingly stressed in the humanitarian world. Some want to move away from the practice of predominantly large international organisations flying in staff to solve the problems." The idea is that local organisations have better knowledge of the environment and culture and can build trust more quickly.

However, one downside is related to safety - according to the trainers. ''They are local staff members, so they don't leave at some point. But what if their lives are in danger? Who is responsible then? And how can localised interpretation of the humanitiarian principles work together with the international expectations? Those questions are subject to debate.'' In essence, this is a good thing, Borgman and Koenig argue. Local and international organiszations are usually more than willing and able to work together with their international colleagues. However, local organisation often receive much less funding. Major UN organisations are increasingly shifting work and resources towards local partners. This has both advantages and disadvantages. "Small local organisations often lack an escalation mechanism where they can say, 'We are unable to achieve the goal, let's try it one level up.' That level often doesn't exist, unless you make agreements with intermediary organisations. So the issue of coordination and keeping all aid workers safe is very complex."

The training's underlying principle is to empower individuals and the organisations they represent to be in control and make well-informed choices

The humanitarian negotiation training at Clingendael Academy

A complex profession requires good theoretical and practical training, and that's what Clingendael Academy provides. Borgman and Koenig: "In the trainings, we never say: you must always do it this way or never do it that way. We present people with the choices they can make in negotiations. We explain advantages and disadvantages of each option - depending on the context. We guide people on what they could consider in their preparation, what negotiation styles they can adopt, and how they can communicate more effectively. The training's underlying principle is to empower individuals and the organisations they represent to be in control and make well-informed choices."

Are you interested in one of our humanitarian trainings? Visit our Humanitarian negotiation page.