Coercive organisations, war and state development in the Levant

This webpage brings together research efforts of the Middle East team of Clingendael’s Conflict Research Unit (CRU) that focused on the rise and role of hybrid coercive organisations in Syria and Iraq between 2017 and 2021.

- ANALYSING ORGANISED COERCION IN THE LEVANT IN TIMES OF WAR

- CASE 1: THE HASHD AL-SHA’ABI: COOPERATION AND COMPETITION IN IRAQ

- CASE 2: PRO-ASSAD FORCES IN SYRIA: FROM RELATIVE AUTONOMY TO GREATER REGIME CONTROL

- CASE 3: KURDISH FORCES IN SYRIA/IRAQ: FROM REBELS TO HYBRIDS

- WHAT TO DO WITH HYBRID COERCIVE ORGANISATIONS IN THE LEVANT

- Acknowledgments

ANALYSING ORGANISED COERCION IN THE LEVANT IN TIMES OF WAR

With Erwin van Veen, Senior Research Fellow

A NEW TYPOLOGY FOR ANALYSING ARMED GROUPS

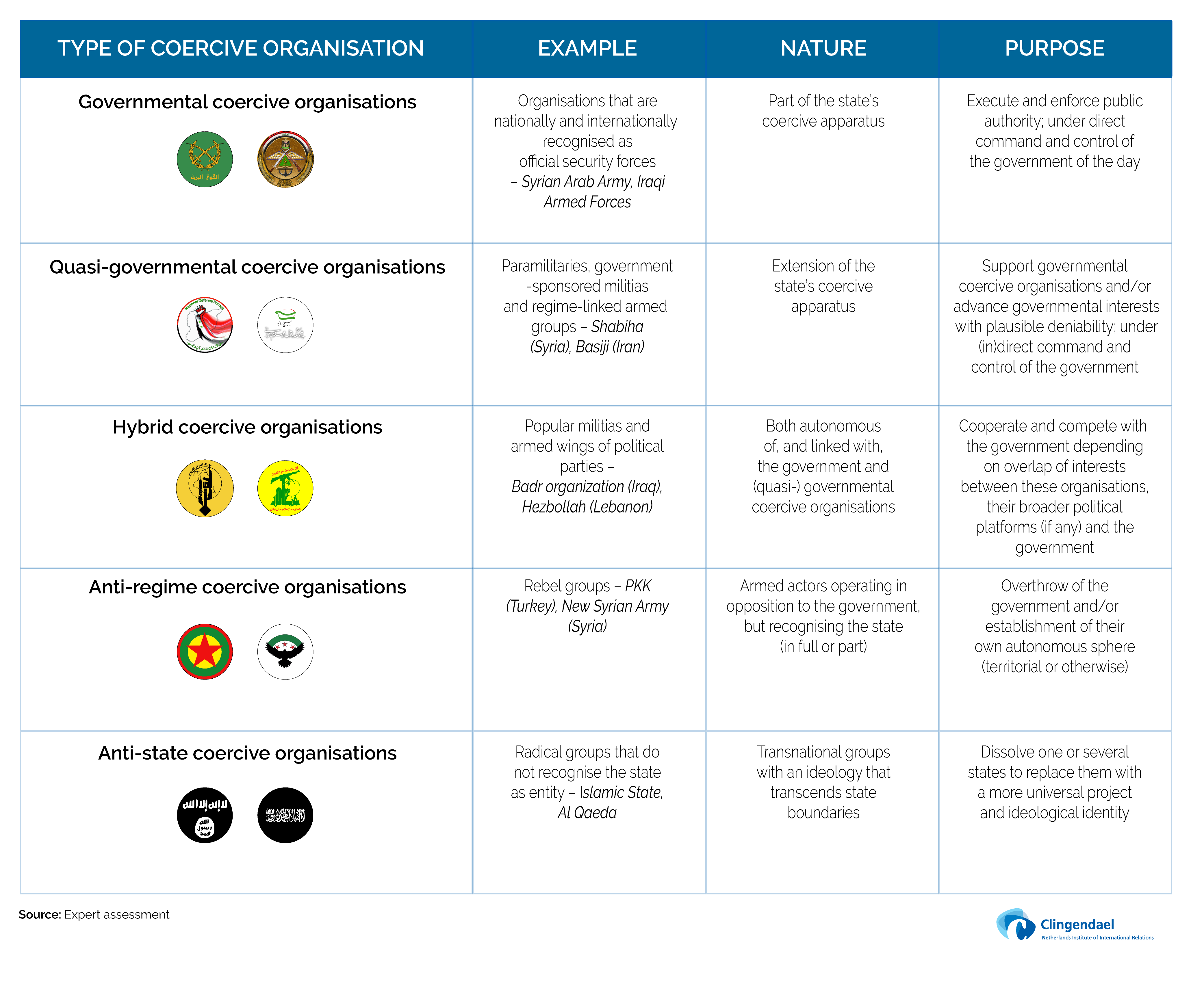

The starting point for our research was the growing realisation that the rather binary understanding of non-state armed groups versus regular armies, which typifies much traditional conflict analysis, did not correspond with the political-security realities of the Syrian and Iraqi conflicts between 2011 and 2021.

To begin with, state authority weakened – but not to the point of collapse – as conflicts deepened in both Syria (2011–2021) and Iraq (2014–2017). In consequence, we witnessed the proliferation of hybrid armed groups as a rational response of elites solicitous to increase their own autonomy and power base without, however, alienating themselves from the government/state entirely. Such hybrid armed groups are different from paramilitary forces in that governments have far less control over them.

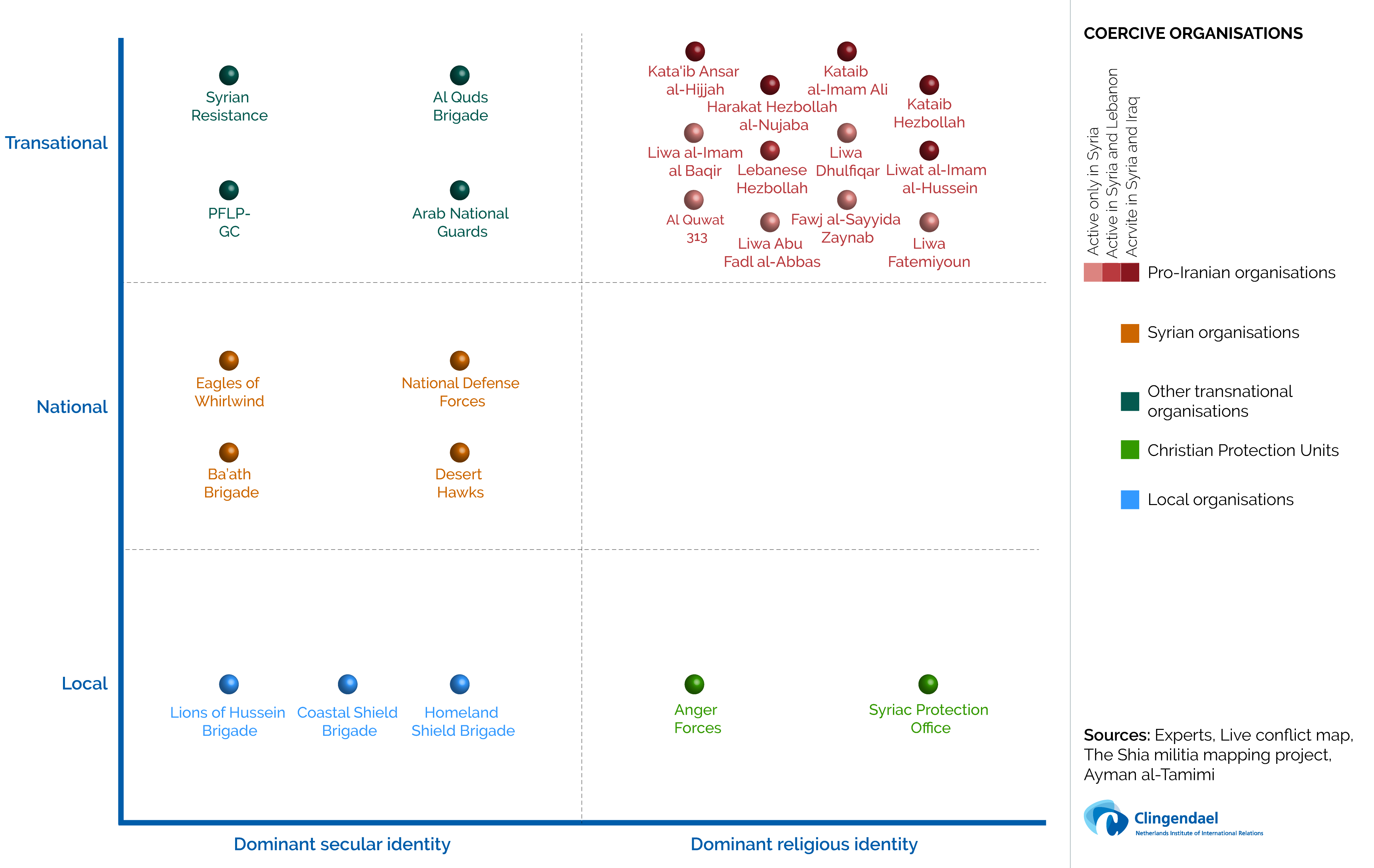

Moreover, radical anti-state armed groups came into being that deviated significantly from the usual rebel group script by advocating and fighting for a more transnational understanding of authority and territorial control beyond the boundaries of existing nation-states and based more on religious identity. For this reason, we developed a broader typology of coercive organisations, ranging from government forces to anti-state coercive organisations. We reduce the distinction between state and non-state forces by defining coercive organisations as follows:

“Actors with the institutional capacity to exert violence on a large scale against outsiders for political purposes and to control violence within their respective strongholds or constituencies”

Click here to enlarge the visual.

WHY DOES A NEW CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK MATTER?

AN OVERVIEW OF SELECTED COERCIVE ORGANISATIONS

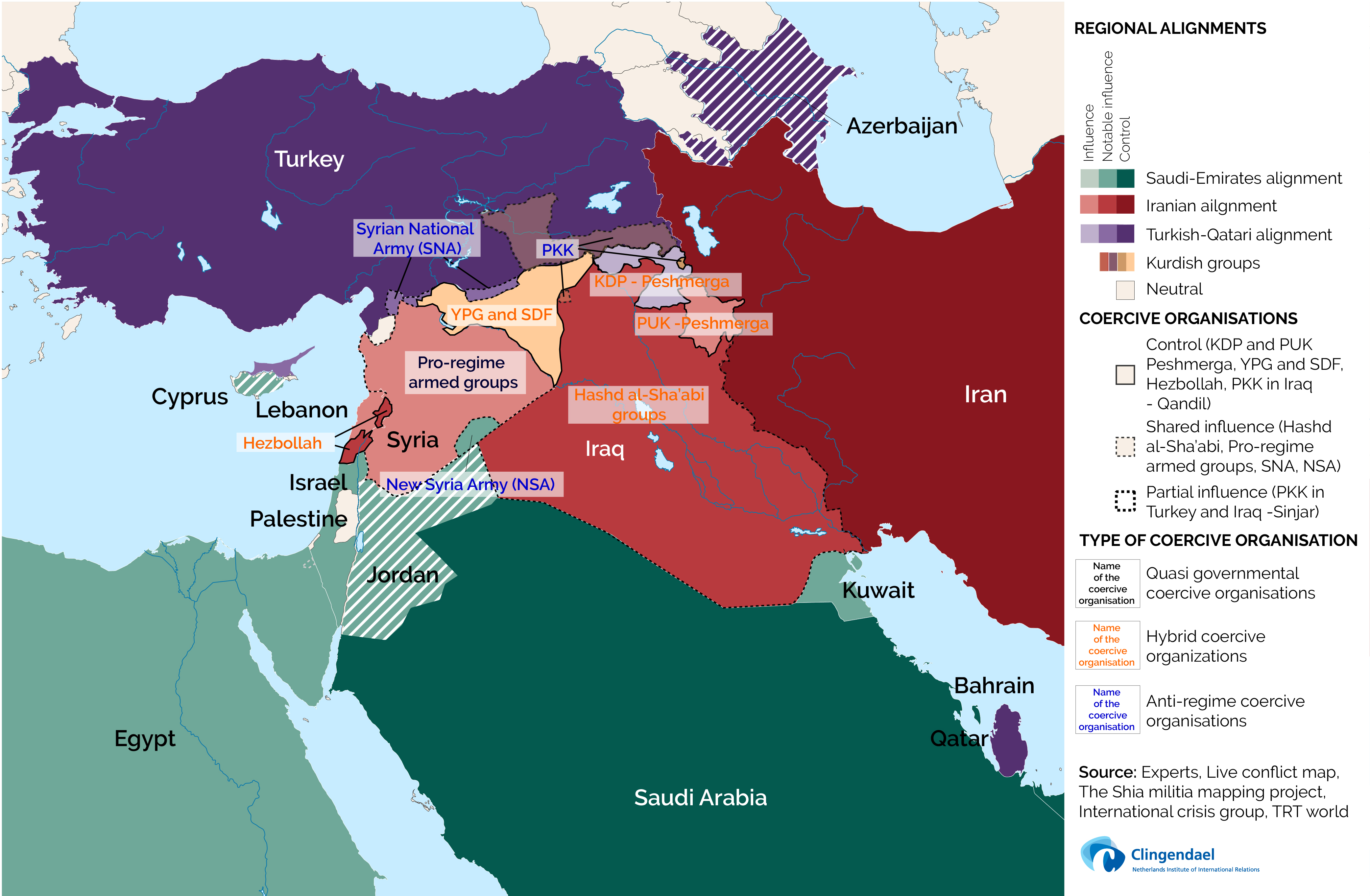

The map below indicates the main quasi-governmental coercive organisations, hybrid coercive organisations, and anti-regime coercive organisations that Clingendael’s Middle East team researched between 2017 and 2021:

Click here to enlarge the visual.

Selected publication:

CASE 1: THE HASHD AL-SHA’ABI: COOPERATION AND COMPETITION IN IRAQ

with Nancy Ezzeddine, Research Fellow at Clingendael’s Conflict Research Unit

HERE TO STAY: PICTURING THE HASD AL-SHA'ABI

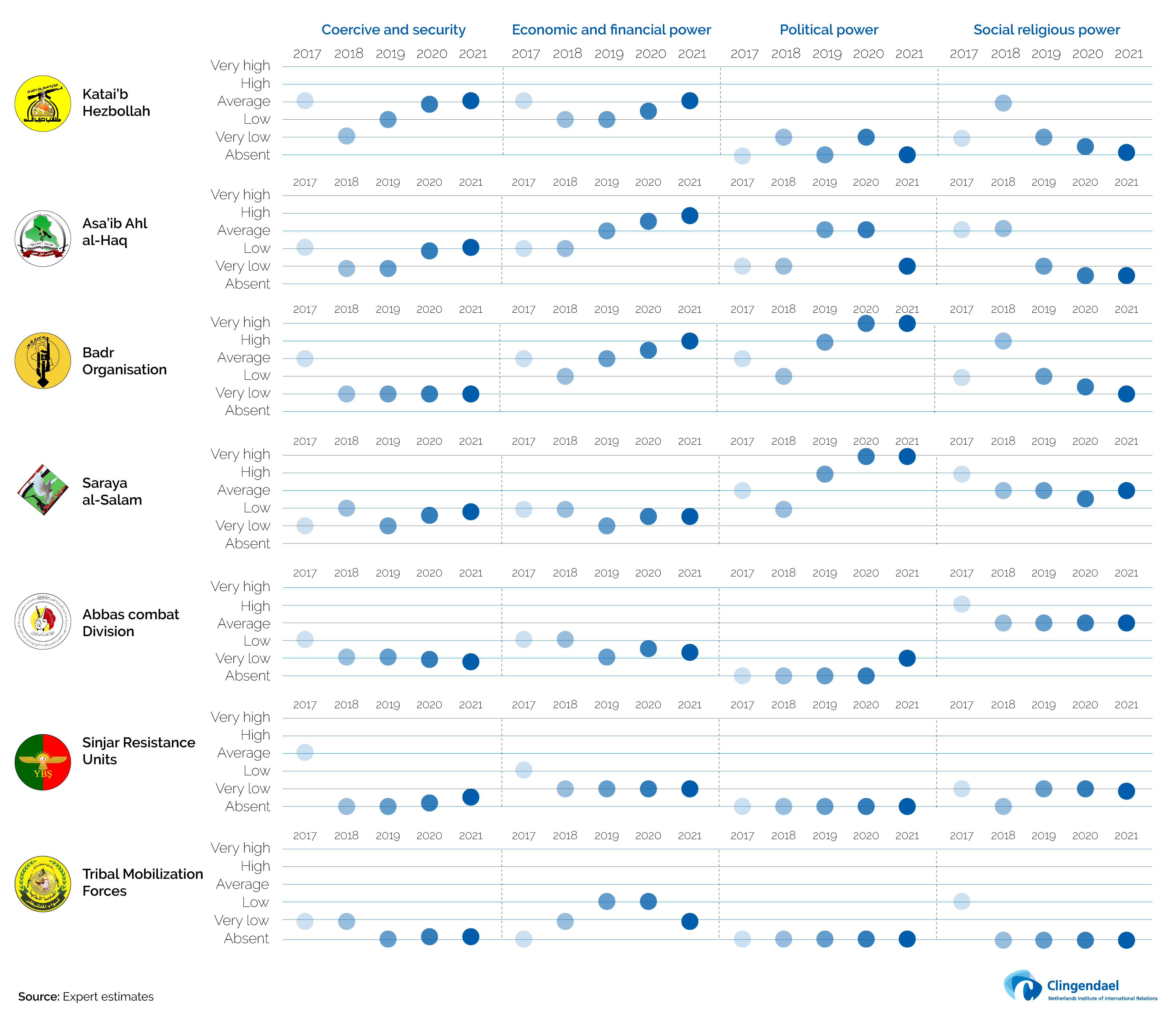

Hashd al-Sha’abi (Popular Mobilisation Forces – PMF) is a collective term that refers to around 50 hybrid coercive organisations of varying coercive capabilities, levels of organisation and attitudes towards the central Iraqi government. While they are grouped administratively under the state-run Hashd Commission, these hybrid coercive organisations operate on a relatively autonomous basis. The Hashd groups have in common that they are revered for having effectively defended the country against Islamic State (IS) and that their place in Iraq’s security landscape remains unclear.

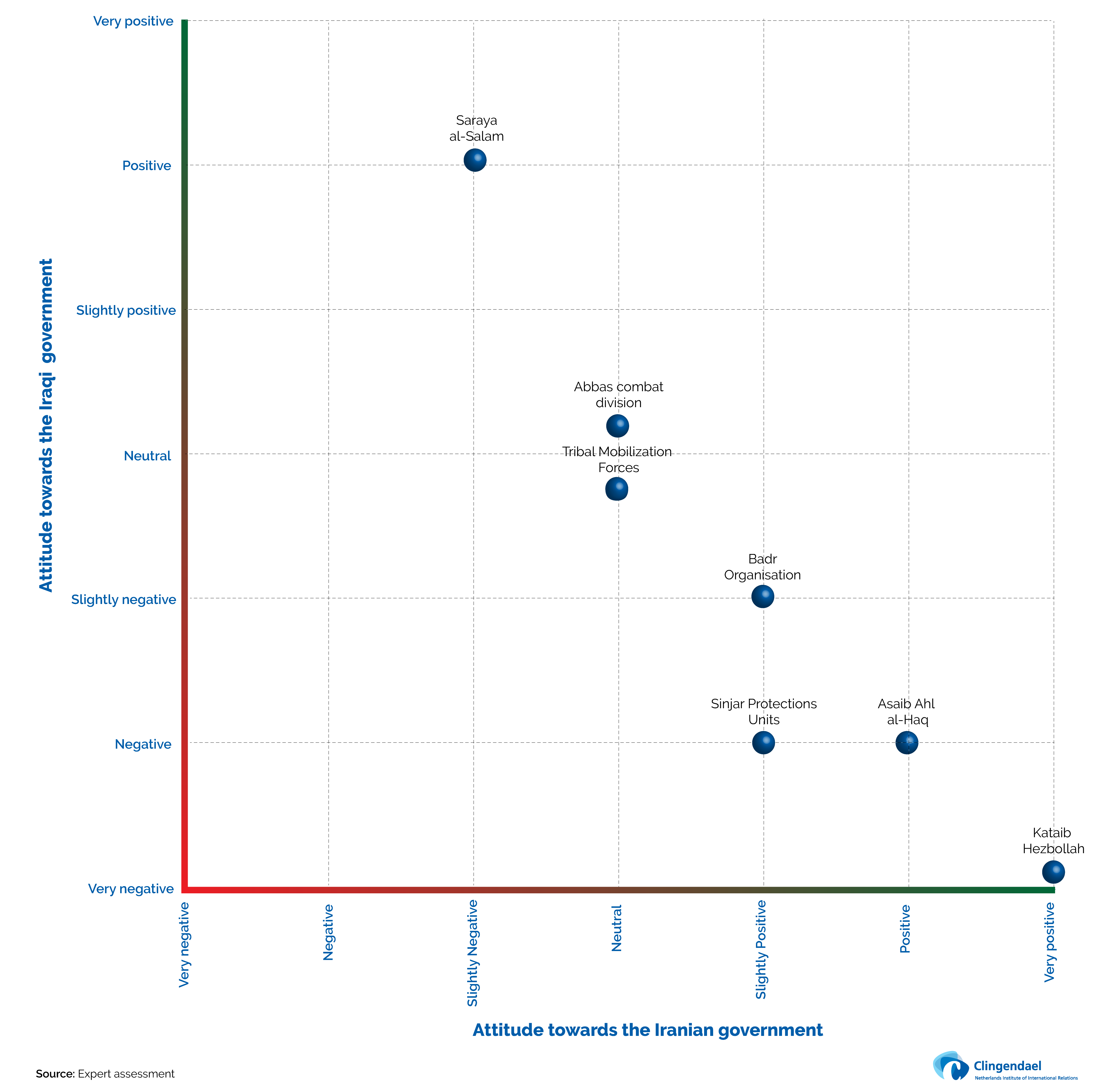

Differences between Hashd groups are larger than their commonalities. Since the 2017 defeat of IS, coercive organisations within the Hashd al-Sha’abi have shown a very different outlook towards the Iraqi government. Some groups expressed their commitment to integrate into the Iraqi Security Forces, or to disband entirely. Others, mostly those linked with Iran, took a more confrontational stance towards the government. They can be grouped as follows:

- There are Shi’a armed groups that benefit from a close relationship with Iran. They include groups such as Asaib Ahl al-Haq, the Badr Organization, and Kata’ib Hezbollah. These groups generally advocate for maintaining the Hashd as a paramilitary force with a high level of autonomy and in parallel to Iraq’s state security forces.

- There are other Shi’a armed groups that are closely affiliated with Iraqi religious and political institutions. This category includes the Shrine (or Atabat) groups that pledge allegiance to the leader (Marjaa) of ’Iraq’s Shi’a Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, such as the Abbas Combat Division. It also includes political leader, Muqtada al-Sadr’s, armed wing, Saraya al-Salam. In general, these groups argue that the Hashd should be abolished in due course and that members wishing to enlist in the army or police should do so. However, neither have pursued such actions.

- There are non-Shi’a armed groups that typically do not operate at the national level and pursue more limited local objectives. These include, for example, the Tribal Mobilization Forces (made up of largely tribal Sunni fighters) and the Sinjar Resistance Units (a Kurdish/Yezidi force).

The success in the fight against IS allowed Hashd groups to secure territorial control of strategic economic sectors and trade routes. The economic power gained, nonetheless, varies significantly between groups. Moreover, the power base of each Hashd group has at least one significant weakness (see below). Generally, the pro-Iran Shi’a Hashd groups have lower levels of socio-religious legitimacy compared with other Shi’a groups such as the shrine groups, but higher levels of economic and financial power. As smaller Hashd groups faded into the background, the Iran-affiliated Hashd groups increasingly asserted control over the PMF Commission, including key administrative functions such as fighter registration, salary payments and deployment planning.

In descending order, the Badr Corps leads the pro-Iran Hashd faction in terms of having the highest level of accumulated power, followed by Kataib Hezbollah and Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq. The power bases of the Abbas Combat Division, the Tribal Mobilization Forces and Saraya al-Salam also vary. Saraya al-Salam is the strongest due to its political representation, its charitable welfare system, and its ability to mobilise constituents. The Abbas Combat Division, despite having a high level of socio-religious legitimacy, has little political influence and limited funding.

WHAT DO THE HASHD AL-SHA'ABI WANT: INTERESTS AND GOALS

ATTITUDES OF MAJOR HASHD AL-SHA'ABI GROUPS TOWARDS THE IRANIAN AND IRAQI GOVERNMENT

Click here to enlarge the visual.

THE EVOLUTION OF THE POWER BASE OF MAJOR HASH AL-SHA'ABI GROUPS

Click here to enlarge the visual.

TODAY: THE HASHD AL-SHA'ABI BETWEEN CONSOLIDATION AND FRAGMENTATION

Our analysis indicates that looking at the Hashd as an umbrella term is an oversimplification since there are significant nuances, even within subgroups. A few anecdotal examples illustrate this point. For instance, while the discourse of the Badr Corps is pro-Iranian, it is much less sectarian than Kataib Hezbollah. In further contrast to Kataib Hezbollah, the Badr Corps also engages in Iraqi politics, and the group works pragmatically with the Iraqi government if and when necessary. The upshot is that each Hashd group must be analysed on its own merits.

A more abstract point to note is that the existence of around 50 Hashd groups creates intense competition over limited options for political representation (e.g. seats in parliament), administrative institutions, and state budget. Although powerful Hashd groups are both Shi’a and Iran-affiliated, Iraq’s Shi’a community has several political centres that are reasonably balanced, such as the parties, charitable networks and armed groups of al-Sadr, al-Hakim and others. Within the Iran-affiliated Hashd groups, substantial differences of interests, outlooks and loyalties exist that make it difficult to fully homogenise command structures and align group interests.

Finally, the January 2020 assassination of Hashd leader Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis has made it increasingly difficult to consolidate the different groups and fill the leadership void. The Hashd is still resilient and retains considerable formal and informal coercive and economic power. However, it is facing growing challenges to its legitimacy, structure and influence. These vulnerabilities could be exploited both by the Hashd’s opponents and its semi-allies, such as the Sadrists.

Selected publications:

- Nancy Ezzeddine, Matthias Sulz and Erwin van Veen (2018). From soldiers to politicians? ” ’Iraq’s Al-Hashd Al-’Sha’abi on the march

- Nancy Ezzeddine and Erwin van Veen (2018). Power in perspective: Four key insights into ’Iraq’s Al-Hashd al-Sha’abi

- Nancy Ezzeddine, Matthias Sulz and Erwin van Veen (2019). The Hashd is dead, long live the Hashd!

- Nancy Ezzeddine and Erwin van Veen (2021). Warning signs: Qassem Musleh and ’Iraq’s popular mobilisation forces

CASE 2: PRO-ASSAD FORCES IN SYRIA: FROM RELATIVE AUTONOMY TO GREATER REGIME CONTROL

with Nick Grinstead, former Researcher at Clingendael’s Conflict Research Unit

THE ORIGINS OF THE LOYALIST NETWORK SUPPORTING ASSAD

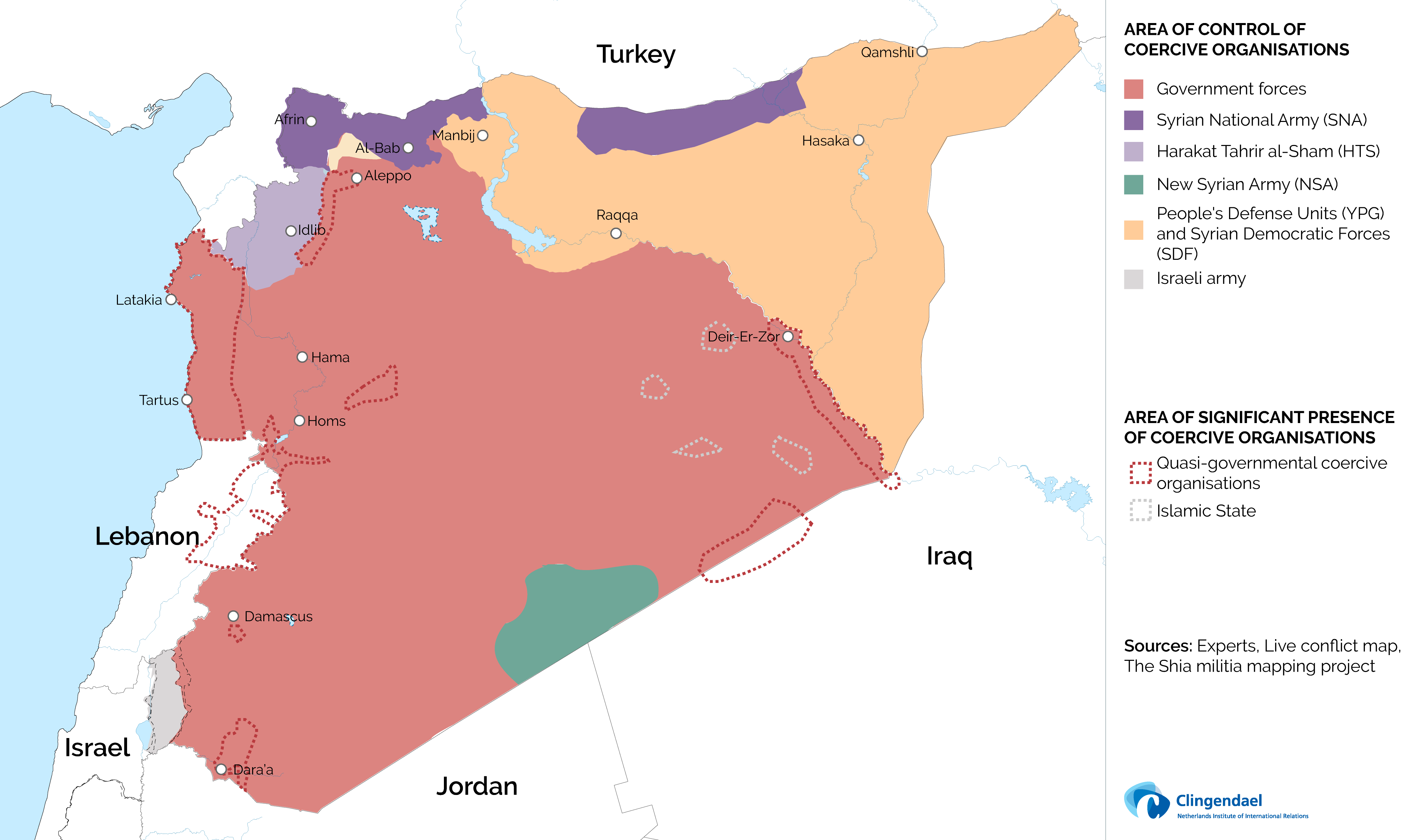

In March 2011, anti-government protests erupted across Syria. The security services responded with force but failed to completely repress the demonstrators. Protesters eventually took up arms, sparking civil war which resulted in the country’s fragmentation. Mass defections from the army led to the Assad regime to seek assistance from local and, eventually, foreign paramilitary groups. The Syrian government began by formalising and professionalising the hundreds of self-defence militias and quasi-criminal gangs (commonly known as Shabiha) that already existed by forming a national paramilitary platform known as the National Defence Forces (NDF) on 5 August 2013 with Legislative Decree 55.

New quasi-governmental coercive organisations, with differing ideological orientations, joined the government’s ranks in the following years. Along with the NDF, other Syrian paramilitary organisations joined the pro-Assad ranks, such as the Eagles of the Whirlwind (pan-Syrian nationalism), the Ba’ath Brigade (Syrian Arab Supremacy) and semi-detached army units like the Qalamoun Shield Forces. In some areas of Syria (e.g. the coastal area) and among some religious communities (e.g. Syriac Protection Office), coercive organisations were formed to protect specific local populations. Iran’s increasing involvement in the conflict led to Teheran-sponsored, primarily Shi’a groups being deployed to support Assad (e.g. Lebanese Hezbollah, Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba). These organisations tend to be religiously oriented and consist mostly of non-Syrian fighters.

Quasi-governmental and hybrid coercive organisations are now a fixed feature of the Syrian security architecture. With the reduction of fighting since 2018, the Assad regime has increased its efforts to exert control over such supporting coercive organisations to increase its influence. One of the regime’s strategies has been to co-opt leading members of such organisations into the ruling elites (e.g. via parliamentary elections). In parallel, the Assad regime expelled unruly members of the ruling elite from positions of power (e.g. Rami Makhlof). Finally, the ruling elite restricted the actions of the hybrid and quasi-governmental coercive groups by limiting their financial and operational autonomy. By contrast, the Assad regime encountered significant hurdles in its efforts to include pro-Iran armed groups into its formal security architecture.

KEY ASPECTS AND THE EVOLUTION OF SUPPORT FOR ASSAD

MAPPING ASSAD'S KEY QUASI-GOVERNMENTAL COERCIVE ORGANISATIONS

Click here to enlarge the visual.

A DIVIDED SYRIA: WHERE DID PRO-ASSAD GROUPS OPERATE IN LATE 2021?

Click here to enlarge the visual.

Selected Publications:

- Nick Grinstead (2017). Assad Rex? Assessing the autonomy of Syrian armed groups fighting for the regime

- Christopher Solomon, Jesse McDonald and Nick Grinstead (2019). Eagles riding the storm of war: the role of the Syrian Social Nationalist Party

- Christopher Solomon and Jesse McDonald (2019). The Role of the Syrian Social Nationalist Party in the civil war

- Samar Batrawi and Nick Grinstead (2019). Six Scenarios for pro-regime militias in ‘post-war’ Syria

CASE 3: KURDISH FORCES IN SYRIA/IRAQ: FROM REBELS TO HYBRIDS

With Engin Yüksel, Research Associate

WAR AS OPPORTUNITY: GREATER KURDISH AUTONOMY IN IRAQ AND SYRIA

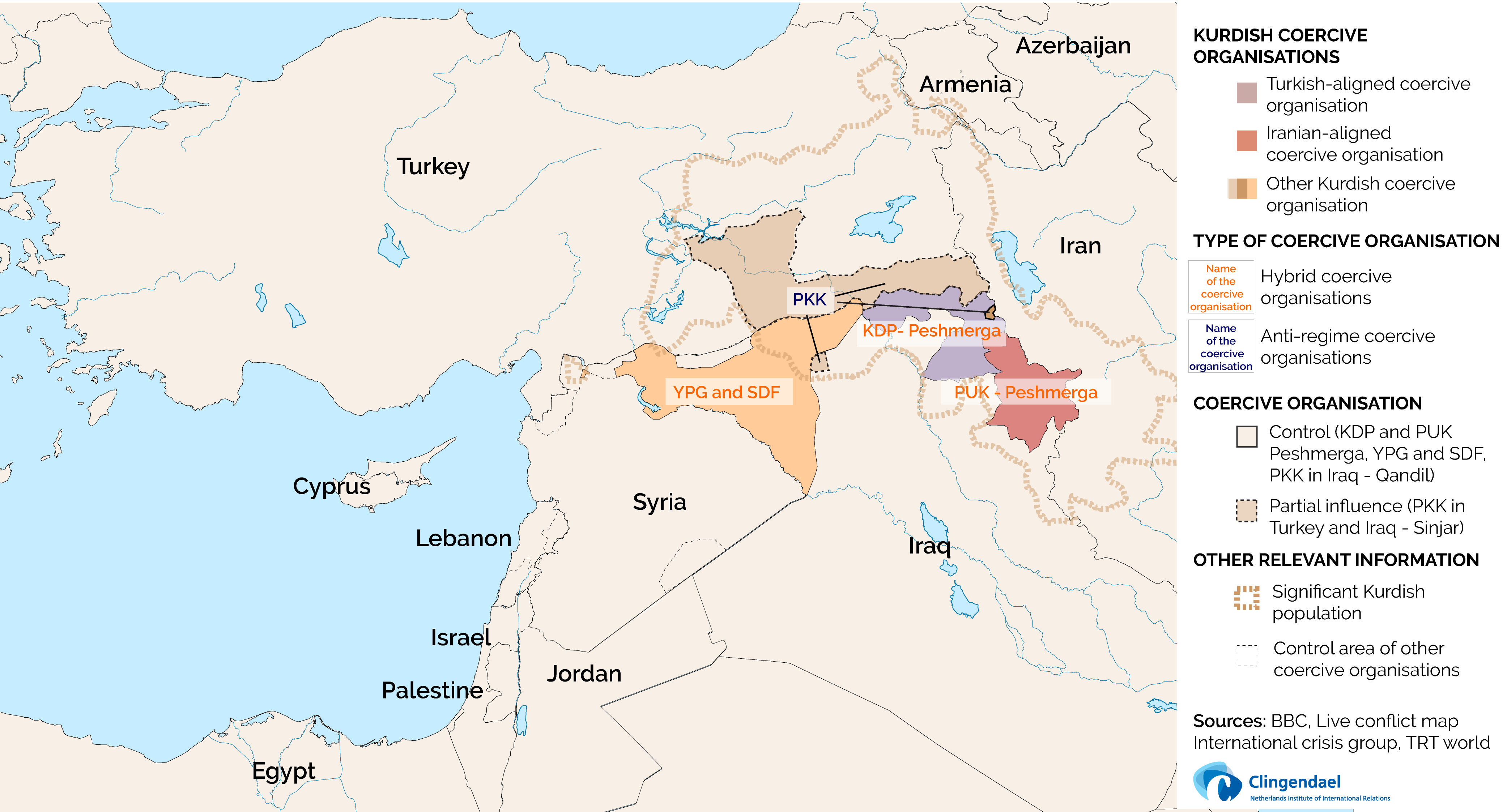

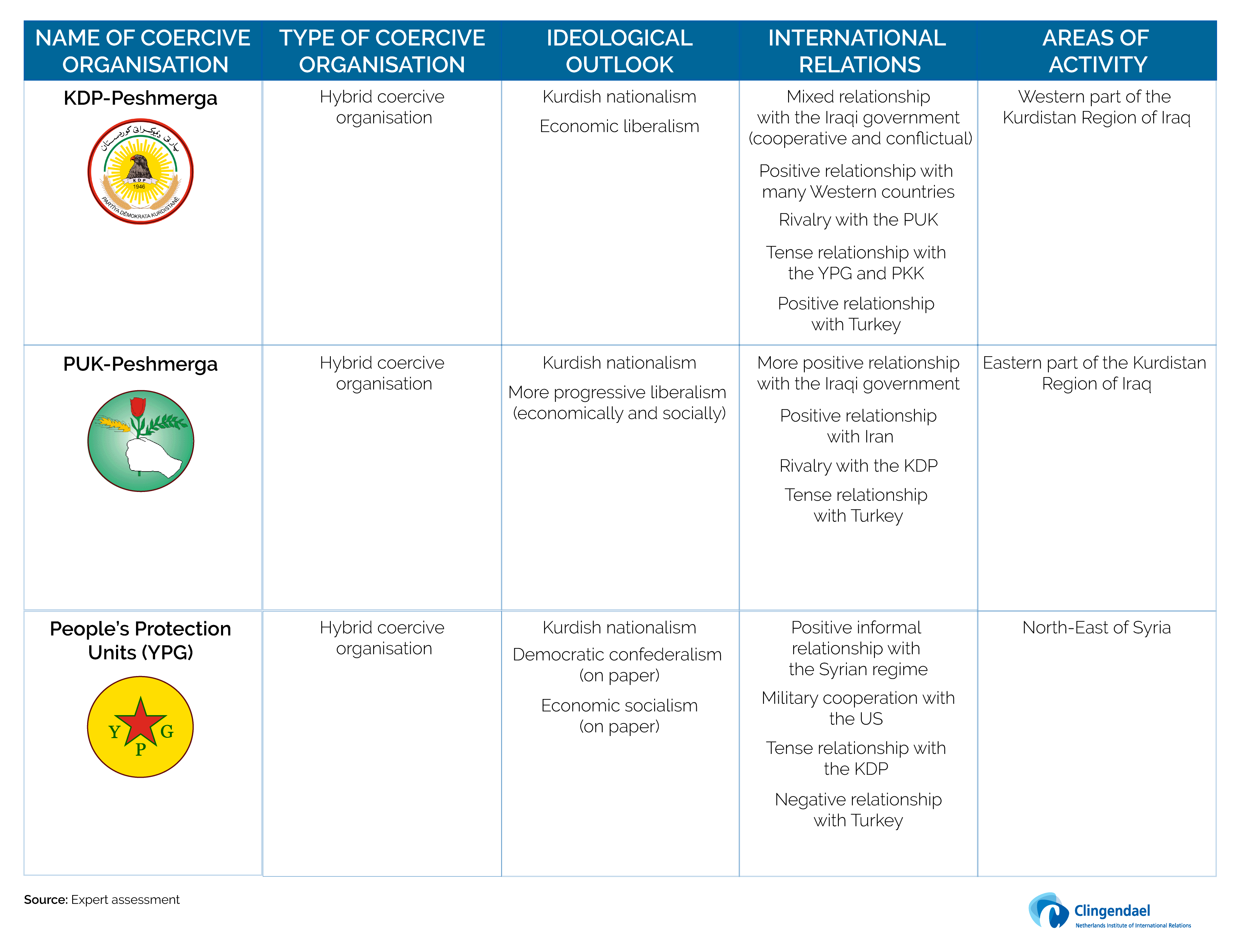

In the wake of the 2003 US invasion of Iraq and during the Syrian conflict, the Kurdish-populated areas of these two countries secured a high degree of autonomy. In Iraq, the 2005 Constitution established the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI). Since its establishment, Peshmerga forces have acted as hybrid coercive organisations that are officially part of the Iraqi Security Forces, and operate autonomously in defence of Kurdish interests. The Peshmerga are politically linked to the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), which runs the western part of the KRI and is dominated by the Barzani family, and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), which runs the eastern part of the KRI and is dominated by the Talabani family.

In Syria, regime-linked coercive organisations left the Kurdish-populated areas of northeast Syria in 2013, which enabled the Syrian Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) to take control. The YPG is linked to the Democratic Union Party (PYD) and to the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK). The war against Islamic State paved the way for military collaboration between the US and the YPG, which resulted in the formation of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) as enabling vehicle given that parts of northeast Syria are inhabited mostly by Syrian Arabs.

The two political entities feature two very different political systems. The KDP and PUK are family-run, socially conservative political organisation with a liberal economic orientation that govern a territory delineated by the Iraqi constitution. The PYD is ideologically inspired by Abdullah Öcalan’s Democratic Confederalism, has a progressive and secular outlook with a socialist economic orientation, and governs a territory it has conquered but to which its rights are not recognised domestically or internationally.

Turkey has adopted different political orientations towards the two Kurdish organisations. While Ankara works closely with the KDP and its Peshmerga in Iraq, it has engaged in a full-scale regional offensive against the PYD and PKK, which it views as identical. As part of this offensive, Turkey has been instrumental in creating, financing and training the Syrian National Army (SNA) active in the northern part of Syria. Moreover, Turkey conducted three military operations in the north, which in two cases targeted areas initially controlled by the YPG-SDF.

UNDERSTANDING THE DRIVERS OF KURDISH MILITANCY IN THE LEVANT

KURDISH POPULATIONS AND HYBRID COERCIVE GROUPS ACROSS THE LEVANT

Click here to enlarge the visual.

SHADED OF GREY? COMPARING THE KDP PESHMERGA, PUK PESHMERGA and YPG

Click here to enlarge the visual.

Selected publications:

- Engin Yüksel (2019). Strategies of Turkish proxy warfare in northern Syria

- Rena Netjes and Erwin van Veen (2021). Henchman, Rebel, Democrat, Terrorist: The YPG/ PYD during the Syrian conflict

- Feike Fliervoet (2018). Fighting for Kurdistan? Assessing the nature and functions of the Peshmerga in Iraq

- Erwin van Veen and Engin Yüksel (2020). The Kurdish question and Turkey’s new regional militarism

WHAT TO DO WITH HYBRID COERCIVE ORGANISATIONS IN THE LEVANT

Ultimately, many coercive organisations are tools to promote or resist political change(s) in line with the interests of those that control, run or support them. In this context, the mix of incentives that determine whether hybrid coercive organisations operate collaboratively or competitively in relation to the government on whose territory they are active arises from three factors:

- The domestic political economy in which they operate - centred on elite interests, relationships and resources

- the levels of foreign support they receive

- the level of social legitimacy and support they command.

But in all cases do hybrid coercive organisations tend to be problematic from the perspective of security provision. This is because they provide it selectively and autonomously. Hybrid coercive organisations do not treat citizens equally and usually defend the privileged position of a particular elite group and its constituency.

The relationship between such an elite group and the state government can vary from being part of it, being both inside and outside of it, and being largely outside of it. This can vary across domains. Depending on how such an elite group and its corresponding hybrid coercive organisation is perceived by the government, and depending on the government’s own coercive capabilities, three engagement strategies are possible:

Incorporation: The aim here is to give hybrid coercive organisations a stake in the state apparatus – power, influence and resources – in exchange for gradual normalisation through standardisation of training, recruitment and promotion, as well as rerouting their chain of command through formal channels. This strategy can work if the state is strong enough to set the terms of engagement.

Accommodation: The aim here is also to provide hybrid coercive organisations with a space in the state apparatus, but with more limited potential for normalisation and standardisation. It will be a more autonomous and less regulated space than in an ‘incorporation’ engagement strategy because the state is too weak to impose its preferences. Born out of necessity, such an engagement strategy can still be preferable to the alternative of taking no action as it can reduce the risk of renewed violence.

The risk of state capture by hybrid coercive organisations can be reduced through longer-term institution-building efforts and by strengthening peaceful counter-voices in civil society and among religious actors. In some cases, targeted sanctions might help to cut off resource flows to hybrid coercive organisations, even though these will mostly be anchored in the informal economy that is hard to sanction.

Confrontation: The aim here is to bring hybrid coercive organisations under the control of the state apparatus, including through the use of force if necessary. Even if this can work, a clever political strategy is required that minimises violence and disruption, for example, by tackling smaller groups first or weakening resource bases and legitimacy before enforcing restraining measures such as eliminating territorial or institutional control on the part of such hybrid coercive organisations. This strategy is only possible when the state has adequate legitimacy, coercive capabilities and resources at its disposal to enter into and sustain the confrontation.

Acknowledgments

The Clingendael Conflict Research Unit wishes to thank Samar Batrawi, Feike Fliervoet, Hamzeh al-Shadeedi, Beatrice Noun, Rena Netjes, Matthias Sulz, Alba di Pietrantonio Pellise, Jesse McDonald, Christopher Solomon and Latif Sleibi for their outstanding contribution to the study of coercive organisations.